Digitized shots of Icelandic snow, glaciers, and misty weather, coupled with real-time camera tracking and Unreal Engine, meant high-resolution environment projections, and lighting, could be captured in-camera to provide unprecedented realism for onstage shooting, in George Clooney and Netflix’s Oscar-nominated sci-fi drama.

In The Midnight Sky, George Clooney and Netflix’s post-apocalyptic sci-fi drama, an Arctic-stationed scientist races to warn a crew of deep-space astronauts about the danger of returning home to an Earth ravaged by a mysterious global catastrophe.

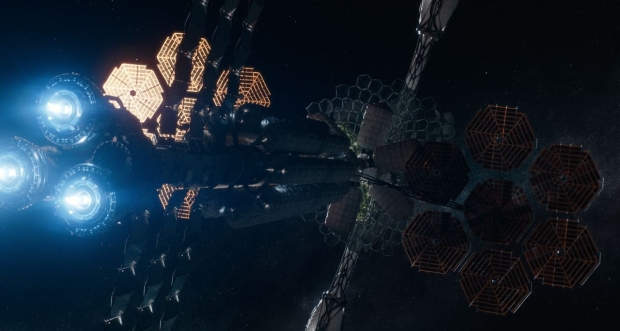

To capture the interplanetary explorers and their spacecraft, as well as the scientist’s polar research station, nearby weather station, and surrounding terrain, more than 1,400 visual effects shots, many in-camera, were produced by Framestore, ILM, One of Us, Instinctual VFX, and Nviz under the supervision of VFX supervisors Matt Kasmir and Christopher Lawrence. For their fantastic work on the film, Kasmir, Lawrence, Max Solomon, and David Watkins just won a VES Award, and have been nominated for the best visual effects Oscar at this year’s 93rd Academy Awards.

Take a look at some behind-the-scenes VFX breakdowns:

For Kasmir, surprisingly, it was the Earthbound invisible visual effects, more than the space sequences, that kept him up at night. “We always knew that zero gravity was going to be hard,” he explains. “What was unexpected was that because of weather conditions, we couldn't shoot all the shots we wanted in Iceland. What filled me full of dread was intercutting shots done on stage with shots shot in Iceland.”

“But with the use of a Roscoe rear projection gel screen with sky panels, we managed to recreate the look of the sky in Iceland, which gave us the light we needed. And then with the special effects from Dave Watkins and his department, we managed to fill the stage with atmos and snow, which looked great. I actually look at the cut now where Augustine [scientist Augustine Lofthouse, played by George Clooney] is walking around in a whiteout, and I can't tell which shot is shot on stage [vs. on location], apart from the fact that George’s beard is fractionally at different lengths because it was a month later. A lot of the best work on The Midnight Sky is absolutely invisible, and most people don't notice it and just think it's either performance [capture] or shot on location.”

Because of a lack of snow in Iceland, the production managed to shoot only half the number of shots needed with Clooney traveling to the weather station, which meant they had to intercut far more stage shots than initially planned. As snow is highly reflective, the rear projection setup allowed Kasmir to “match the skies we had in Iceland in our practical shots.” “Practical snow is dead because there’s not enough light,” he continues, “and that [the Roscoe setup] enabled us to really kind of match the practical shots.”

The production also used a huge LED volume and other virtual production technology supplied by ILM StageCraft. According to Kasmir, “They created this highly reflective set with a large aspect window looking at the glaciers. Having done a lot of Alpine views in the past, you know, if one is to shoot it for real, you either expose for inside, in which case the outside is blown out, or you expose for the view from the window, in which case the inside is very dark. If you put a bluescreen outside, what happens is the DP and the director obviously choose to expose to the interior, but when you come to put in the outside, they want to see a perfect Alpine view, which means it ends up looking very composited. My ulterior motive was that I wanted it all in-camera, because I felt a lot of these shots could end up looking a little bit manufactured.”

“We tried to limit the number of visual effects shots that we were doing in post,” he adds. “We had a very tight schedule. We knew we had our work cut out for us out with the zero gravity. The thought of 100-200 snowy earth exterior shots… it just made sense to do it this way.”

In a complex and sophisticated use of Unreal Engine 4, the ILM team took a wide variety of data from Kasmir’s Iceland plate shoots – done with a 3-Alexa 65 camera array giving a 270-degree vista – shot at four times during the day, as well as glacial photogrammetry surveys and close action LiDAR scans, to provide the stage shoot with different skies, different sun positions, and different weather conditions projected on the LED wall. It’s the same system used on The Mandalorian. “We digitized the environments, and ILM processed this and projected the four times a day onto the geometry, filled in any holes, and supplied us different skies, different sun positions, and different weather conditions, including snow mist and different types of falling snow,” Kasmir reveals. “So, in our armory, when we were playing this back on the LED screen, we could be absolutely selective in the weather outside, time of day, and position of the sun in conjunction with our sets.”

Using motion tracking cameras on set, they were able to track the practical camera positions and use that data to position high-resolution imagery on the LED wall exactly where those cameras were focused. If the practical camera was looking out the observatory window, the system would optimize the area of the LED wall where the camera was shooting. “The motion capture cameras are very similar to a mocap system where a performer is dancing in front of the capture volume,” Kasmir describes. “But it wasn't capturing a performance. It was capturing the movements of the camera. And in real-time it was feeding the angle that the camera should be looking at onto the screen, and projecting onto that area of the screen using Unreal Engine 4.”

Kasmir goes on to say, “It’s an incredibly sophisticated system,” noting that the beauty of the ILM system is that only the frustrum area that the camera was looking at was rendered at 4K. The rest of the LED screen, which was just used for lighting purposes, was only rendered at 2K. So, to the naked eye, you would see the frustrum area move around and parallax would change.

For the space shots, the team made extensive use of previs that once edited, allowed them to work out methodologies for getting needed shots, which made use of both Nviz and The Third Floor’s virtual camera systems. “That was fortuitous,” Kasmir notes, “Felicity [Jones] turned out to be pregnant. And I mean, it didn't feel that lucky at the time, but it turned out to be to our advantage because she couldn't travel, and her wire work was a bit limited. So, we engaged ILM’s Anyma system, which captured facial performances.”

“It’s a testament to the experience of animation supervisor Max Solomon and Framestore VFX supervisor Chris Lawrence, who both worked on Gravity [for which Lawrence won a best visual effects Oscar] that we were able to take a performance that was directed and performed in front of an ensemble cast, or seated in chairs, and use it to drive our digital characters.”

There were multiple shots, particularly the airlock sequence, as well as the exterior spacewalk, where the characters are entirely CG. “I actually struggled to recognize that,” Kasmir admits. “I mean, there's one shot where Maya is brought in and strapped down on the airlock floor that’s 100% CG, and yet I don't notice. Everyone's going to look at it and think we shot it. Maybe there are wire removals. But no, it was 100% CG lit in three dimensions.”

The production team broke down the film to determine where, and with which cast members, they could use conventional CG doubles, particularly if they’d be small enough onscreen, or where they’d need the Anyma system. “This allowed us to cherry pick the key performances that we needed to shoot on wires, or against our set,” Kasmir says. “It was incredibly liberating. We had a production meeting where we figured out we didn't have enough time to shoot half the action. But we knew we could get a controlled facial performance from our actors in a capture volume.”

“Max and Chris did control the eyelines,” he continues. “That was the only thing we've manipulated in the actors’ performance. If you’re just being directed in a black, empty volume, it's hard to know where you should be looking. But everything else is 100% theirs, in 100 performances over 200 shots.”

Reflecting on the film’s visual effects production, Kasmir concludes, “On wrap, I said to the crew, ‘This is as close to perfect a film as I've ever worked on.’ It's a testament to the producers and, George, Grant [Heslov, one of the film’s producers], Martin [Ruhe, the film’s DP], Jim [Bissell, the film’s production designer], and Jenny [Eagan, the film’s costume designer]. They trusted me with all their views and all their vision. And it paid off.”

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.