Stuart Little is coming to the screen in a big way this fall. Ilene Renee Gannaway visits Sony Pictures Imageworks to see the work that has gone into making this CGI mouse real.

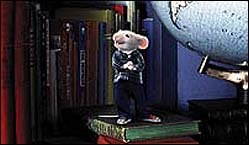

Mickey. Fievel. Jerry. And now -- Stuart. Throughout animation history, mice have always played a crucial, yet ironic role in making us re-examine our own humanity, in making us ask that highly existential question, "Are we mice, or men?" On December 10, Columbia Pictures will introduce the newest animated mouse bent on burrowing its little way into our psyche and our hearts. Based on the beloved 1945 children's classic by E.B. White and brought to vibrant life by Director Rob Minkoff and the crew at Sony Pictures Imageworks (SPI), Stuart Little tells the story of a tiny mouse (voiced by Michael J. Fox) who is adopted by a human family. And not as a pet. As their child. Yes. You heard me. Because he is obviously so different from his adoptive parents and brother, both he and the Littles learn to appreciate the true meaning of family and home. As producer Douglas Wick explains, "(The Littles) don't really see a mouse. They see another creature who seems alone, like an orphan to them, and their hearts tell them that he should be the new member of the Little family." From our first glimpse of this extremely lovable, "you just gotta hug him" character, it is astonishingly clear that Stuart isn't your typical, run-of-the-maze rodent. He may have white whiskers and a pinkish tail. He may be only three inches tall. And he may look at the world through black, beady eyes. But he also walks on two feet, talks, thinks, emotes and even drives a snazzy red sports car. And, sporting everything from a formal tux to trousers and high-tops, he looks like he just walked out of a Gap ad -- "Everybody in corduroy -- size extra, extra, extra, extra small."

A Man or A Mouse? In fact, most of the filmmakers claim that Stuart isn't really a mouse at all. Beneath all his snow-white fur lurks an intelligent, clever and compassionate human being.

"I've always felt that Stuart was a person and that he actually saw himself like any other kid would look at himself," explains SPI Animation Supervisor Henry Anderson. "He has some characteristics of a mouse, but he's really not necessarily a mouse. Part of the message of the film is not to judge a book by its cover."

Stuart may be cute and hip, but on a more important level he functions as a metaphor for adopted kids who struggle to fit into their new families. Though the slightly-eccentric but extremely warm-hearted Littles (Geena Davis and Hugh Laurie) love Stuart like they gave birth to him, their real son George, (Jonathan Lipnicki), isn't so sure he wants a teensy-weensy mouse for a sibling. In fact, when he told his parents he would like a little brother, he didn't think they would take him so literally.

Adding to the sibling rivalry are Stuart's physical limitations within the Little household. Let's face it. He's short. Really short. Brushing his teeth with an oversized toothbrush poses a Herculean challenge as does escaping from a merciless washing machine.

Producer Douglas Wick believes that Stuart encapsulates just how frustrating and frightening childhood can be. "Every child feels like a different species than his parents," he observes. "As a child, you're always looking at the world at knee-level, and it seems overwhelming and scary. A protagonist like Stuart -- who has a big heart and can go out into the world and problem-solve -- is very inspiring."

A more formidable problem than your average Kenmore appliance materializes in the form of Snowbell, the Little's pampered pet cat (voiced by Nathan Lane) who can't stand that a mouse occupies a higher niche in the family hierarchy than he. As a result, the talking feline (whose mouth moves with assistance from the folks at Rhythm and Hues) enlists the help of a menacing street cat to oust Stuart from the place and people he is beginning to call home.

Clearly, Stuart faces more daunting obstacles in this adaptation than he does in White's original story in which the mouse quickly ingratiates himself in the family and then leaves them -- without a backwards look -- to set off on his own adventures. Barry Weiss, Senior Vice President of Animation Production at SPI, explains that it was necessary to deviate from the original story in this fashion in order to emphasize the thematic importance of family. "Stuart Little is about how a child is going to integrate into a family, what makes a family," he says. "In the book, Stuart just runs off into the sunset, and we didn't want to do that in the movie. We want the resolution."

Giving Birth To Stuart

Making Stuart appear to be a living, breathing human-like mouse was one of the greatest challenges for the multi-talented crew of artists and animators at Sony Pictures Imageworks, the innovative digital production company that created the visual effects and computer animation for such films as Anaconda, Contact and James and the Giant Peach. Stuart Little is their first solely-produced film. The SPI facility on the Sony lot is certainly impressive, boasting state-of-the-art computers and software. Scattered among all the high-tech, "I couldn't even begin to explain what this does" stuff are hundreds of drawings of Stuart, his home, his boat and his car. Though it looks like he just won it big on The Price is Right, all of these drawings and renderings are the result of a very long and intensive process the crew underwent to determine the best way to make Stuart real. "We couldn't find a trained mouse that could wear clothes, walk on two feet and deliver lines," jokes co-producer Jason Clark. "So we had to come up with a way to use technology to tell the story. What we did with Stuart Little wouldn't have been possible five years ago." SPI did experiment with a variety of technologies, including animatronics and stop-motion techniques; however, Stuart's character and the fact that he interacts with a live-action world necessitated that he be 100% computer-generated. Photo-realistic techniques were employed to "make sure that when you see him in a scene with the actors or animals against the background, he's completely believable, and you don't think for an instant that this was computer-generated," explains Visual Effects Supervisor, Jerome Chen. However, the particular process used to create Stuart had never been done before. It is a process which, according to Senior Visual Effects Supervisor John Dykstra, a renowned visual effects veteran, involves "creating a character out of whole cloth whose performance could be integrated into a live-action scene with no seams -- a character that has fur, a character that wears clothing, and a character that is lit to match environments. You have to have a character who walks, talks and responds to the live-action world around him with genuine emotion. If you don't empathize with Stuart, we haven't done our job." Dykstra, one of the founders of Industrial Light & Magic and an Academy Award winner for his work on Star Wars, says that the key to making Stuart effective is that "you have to believe that this guy has a soul. And a singularity of personality. And that's a huge challenge -- a challenge to me that was as great as the concept of Star Wars."

Ironically, nobody even knew what Stuart looked like by the time Minkoff, who also directed The Lion King, and his crew started shooting the live-action sequences. Chen recalls, "We didn't have a full blown test of Stuart when we started shooting. We had a whole bunch of pieces of him. But we had not shown the studio the screen test that we were supposed to do...so nobody even knew what he was going to look like."

Stuart the Supermodel

The artists began their initial work by sculpting 30 or 40 different clay maquettes, or 3D statues, of Stuart which illustrated the various possibilities for the character's look. Weiss remembers, "The process sort of became, `I love that head, I hate the body. So let's take that head, try it with this body and put it in that pose and see what we get.' We got to the point where we saw the Stuart that we liked." Problems soon arose, however, once fur was placed on the model. "He turned into a koosh ball," laughs Weiss. "When we put the fur on there was no definition left. So we wound up having to sculpt in a lot more detail. It was almost like looking at this little mouse who had been working out for about three months. But once we put the fur over that, it softened those harder edges and we wound up with exactly what we wanted."

Anderson and his animation crew also conducted research on Stuart's personality and movements. How would he act? What would his facial expressions and body positions look like? Ultimately, they drew their inspiration from Michael J. Fox's voice-acting, Buster Keaton films and mime artist Bill Irwin. "We taped Irwin doing all sorts of performances as to what Stuart might look like when he talks to the Littles, how he would look when he brushes his teeth with this oversized brush," says Anderson. "Bill's such a great actor, and his influence gave Stuart a really nice rhythm. All the animators got copies of those tapes and looked at them throughout the process." Though Fox, Keaton and Irwin influenced Stuart's human personality, the animators had to reference a different species to get his anatomy right. So at one point, the real McCoy was brought in -- a live rat. "The rat was very helpful," notes Anderson. "We studied his face, primarily looked at how his nose moved, how his cheeks moved, when his eyes blink, how his lids work." Minkoff adds, "We needed to find different ways of exaggerating what seems natural about a mouse, without falling into the trap of being too cute. A texture and an edge had to remain."

Quiet As A Mouse On The Set

Meanwhile, back on the set, the actors rehearsed their scenes with an absent leading man...er, mouse. Apparently, Stuart was too busy being coifed, clothed and...well, created to show up for work. Laser pointers were used to show Davis, Laurie and Lipnicki were Stuart would stand in relation to them, and they would improvise holding Stuart in their hands. Chen explains, "We'd practice with the puppet, we'd have the maquette on set, and we'd practice the choreography of how they're going to hold Stuart." The experience became so real to the actors that at one point, states Minkoff, Laurie actually mimed gently setting Stuart down on the floor even though the camera wasn't rolling. Apparently he didn't want to harm his fellow, furry thespian. Next came what's called "the reference pass." According to Chen, three different kinds of racquetball-sized balls were used to reflect the kind of real-world lighting that would be reflected in Stuart's eyes and on his fur. "The actors would hold the balls in their own hand, and that way we could see the way the balls pass through the lighting, if they cast shadows at a certain moment," he says. "Then, using these balls, the animator has to place many different lights on (the animated) Stuart to make him look like he's moving through different light sources in a particular space."

Once the scene was shot, the selected take was then scanned into the computer, color timed and sent onto the match-move stage where, notes Chen, "the artist re-creates in the computer the camera that was used to actually photograph the live action plate. And by re-creating it, he has to match the type of lens that was being used. The computer graphic camera does the same type of movements as the real camera does, that's why it's called match-moving. It matches it so that the perspective will work."

Chen opines that match-moving is perhaps the hardest part of this labor-intensive process. "If the matching isn't done to the highest level, you'll see Stuart slipping, or he won't feel like he's walking on the surface or sitting or walking up the steps or whatever it is that he's interacting with. If the perspective doesn't feel right, there'll be something odd about the shot." Clothes Make the Mouse After match-moving, the shots were sent on to be animated by Anderson and his team of 30 animators. According to Anderson, one of the biggest creative and technical concerns was having this many people work on just one character. "Because when that happens," he says, "you have to worry about the consistency of the character. Are 30 people going to be able to make it look like the same character all the time?"

Part of maintaining this consistency was assigning different scenes to different animators based on their own artistic strengths. "There was an audition process...which was to evaluate crew so Henry would know how to cast a shot," Weiss mentions. "It wasn't, `You're bad, you're good.' It was who understood the character the best for a particular kind of scene. Who's best with this time of day, that kind of thing. We divvied up the scenes based on people's certain strengths for animation."

After Anderson and Minkoff approved the animation, the scenes were then sent onto Jim Berney, the Computer Graphics Supervisor, who essentially dressed and put fur -- more than 300,000 hairs -- on the heretofore naked Stuart. Clothing and fur, while not new to computer animation, had never been attempted quite on this scale before. In addition to consistency of character, clothing was another extremely difficult and challenging task because "you're doing so many layers of computer generation," Anderson explains. "As amazing as computers are as calculating tools, sometimes they're very dumb. It's very hard for them to detect where one layer of clothing bumps up against another, where it bumps up against skin. "There were a few instances where we needed to go back to the animation stage and modify a pose here or a pose there to accommodate the calculation of the cloth," he adds. "That was rare. Most of the time the animators were able to focus on the performance first and foremost and the clothing was modified to fit the performance." So where did Stuart shop for his cool threads? Though the artists admit that some of his clothes were Gap-inspired, Stuart actually had his own costume designer, Joseph Porro (Godzilla, Independence Day), who did all the costumes for the movie. "He would give us his sketches for the different outfits," says Berney. "We'd get miniature versions of cut-out panels, the same as you would have for anything you would sew. We would put those on the maquette. If they fitted all right, we would scan the sketches into the computer and then trace out and model each of the panels with a program that was built, Alias|Wavefront, that would basically stitch it together and put it into animation." Naturally, the costuming didn't always go smoothly. Berney remembers a few simulations were Stuart inadvertently walked out of his clothes. "We tried leaving his jacket unbuttoned for a casual look. But when we tested this, his jacket slipped off him and he just stepped out of it," he recalls with a chuckle. "There were also moments when his clothes wouldn't stop moving," adds Berney. "That was kind of scary for a while. But we soon overcame those problems."

The Final Stages: Lighting and Integrating Stuart While Stuart was getting dressed, the color and lighting artists were placing the appropriate, photo-realistic lights on him. They needed to ensure that Stuart received the exact same lighting as his live-action counterparts. "We'd look at how Geena and Hugh or the other actors were lit in a scene and have Stuart lit from the same direction so that when they cut back and forth he feels like he's actually there with them," remarks Chen.

Once Stuart and his clothes were lighted properly, the scene would then go on to the compositing stage which, Chen explains, "combines all the different elements that the artists create that make up Stuart. They create everything separately. His head is on one layer or element, his eyes are a separate element, his whiskers are a separate element, even his teeth are a separate element. And all the layers of clothing are a separate element. We create these separately and combine them in this compositing stage because it gives more control to finesse each individual layer.

"This way, if we have to re-create one part of Stuart -- maybe his tie is wrong, or his hands are too dark -- we can focus on the small pieces and recombine them. We don't have to re-render everything."

Finally, Stuart was integrated into the live-action scenes in such a way as to make the audience believe he had been there all along -- showing up for those long and exhausting days on the set even though he never really sat in a actor's chair, occupied a posh trailer or nibbled on camembert from the catering truck. Remarkably, his performance reads as natural and convincing as Davis' and Laurie's, drawing us not only into his home and situation but into his genuine emotions as well. As far as we're concerned, he's a regular actor with a SAG card.

"The strongest thing I can say about the film," concludes Weiss, "is that after about a minute or two you stop gaping at this technical achievement. You don't notice that he's a digital character. Any visual effects person worth their salt will tell you, `If you didn't notice what we did, then we did a good job.'"

Ilene Renee Gannaway is a freelance writer who served as Director of Development for Turner Feature Animation and as Manager of Development, Motion Pictures for Hanna-Barbera Cartoons. She is currently pursuing her Master's Degree in English Literature and likes mice okay but thinks squirrels really rock.