This month, Dr. Toon gets animated with historian, film preservationist, producer, promoter of animation festivals and events, and rather prolific author Jerry Beck.

I met Jerry Beck for the first time in 2003 while visiting L.A. Not long after that he gave me the opportunity to work with him and several other contributors on The Animated Movie Guide. I was aware that Jerry had written some great books, but I was amazed at all the other projects he has been (and continues to be) involved with, every one of them in the area of animation. Jerry truly lives an animation buff’s dream life, and recently I got in touch with him in order to have him tell us a bit about his career to date. It’s a wild and frantic story, one well worth hearing and enjoying.

Dr. Toon: Jerry, you’ve had a career as a historian, a film preservationist, a producer, a promoter of animation festivals and events, and a rather prolific author. Talk about the path that led up to the development of Hornswiggle, your very first animated cartoon.

Jerry Beck: I had wanted to make a cartoon ever since I was a kid, certainly since high school. I always drew comics throughout school, underground-type comics. Robert Crumb, Marvel Comics, Superman comics — everything I grew up with in the ‘60s and ‘70s influenced me. I graduated high school in the mid-’70s, and I wanted to be an animator. I had rediscovered the Warner Bros. toons on television. It wasn’t really until my high school years that you could say I “caught the bug.” I used to watch the Warner cartoons when I came home from school, and I realized, “These are great!” I was into superheroes, stuff like (Jack) Kirby and (Jim) Steranko. Realize that to be into comics in the early ‘70s was kind of weird, not as accepted as it is today.

Then, to rediscover cartoons, to really admire the craft of the animation, the humor, the voice work of Mel Blanc, well, as a teenager that was even weirder than saying you were into comics. You’re talking about funny animals! But I left the superhero stuff behind and really got into animated cartoons. That included the emerging anime films, the old Superman cartoons, Jonny Quest — you know, things for the red-blooded male! I loved the Warner toons the most and that’s when I started to research them. I could see that in the 1970s then animation was at its point of death. It was just horrible, and there was nothing happening. Even studios like Disney were doing their worst work.

(Jerry and I are just about the same age, and at this point our lives, we’re eerily similar. However, Jerry’s drive to learn about and practice animation took him in directions I still sometimes wish I had taken.)

Here I was in New York City, where we had a wonderful animation community made up of all the old-timers like Jack Zander and Howard Beckerman, who was a real mentor. I would go to ASIFA meetings and the Museum of Modern Art. I got cultured in foreign and independent animation and I tried to figure out how to get into that business. After high school, I bolted to the School of Visual Arts and enrolled in a bunch of courses in cartooning and animation. I got to meet people there like Tom Sito and Dan Haskett.

I became friends with this animation community. By taking these courses — this was around ‘75 or ‘76, I personally came to feel that I just didn’t have it. Working next to people like Sito and Haskett, well these guys could really draw and animate. These guys were amazing, and there was no work for them. None. And I was still drawing stick figures, really. I felt very discouraged and didn’t feel as if I had a chance to be in animation. I lost my own initiative to be in the field as an artist. Part of what you do at the animation classes is shoot a pencil test and make a film, and I did. It was a little film about a guy with a ray gun, just really simplistic, something to demonstrate animation. I remember thinking, “Hey, there’s my little guy moving!” It wasn’t very good; I’ve got it buried in my closet somewhere, future, “classic Jerry Beck DVD bonus material!”

But at the same time I was going to school, they were showing cartoons on 16mm projectors and I started to collect cartoons. That was where I got into the history aspect. I realized around ‘75 that, as much as I loved these things, there were no books about them. There were no books that listed all of the Warner cartoons, or books about the histories of the studios. I meandered over to The New School For Social Research, another school in New York, and that’s where Leonard Maltin was teaching a class on the history of animation. He had just come out with his book on the Disney films, and The Great Movie Shorts, which I loved. I had to take this class, even if it was just to meet Leonard, and I wanted to encourage him to do a book like The Great Movie Shorts, only about cartoons.

(Lucky guy! At this time my classes consisted of abnormal psychology, theories of personality and learning the now-outmoded original version of the MMPI. Maltin was not among my profs, and the ones I had did not know that Bob Clampett was the original animator of Daffy Duck.)

From that first class, we ended up becoming friends, and we still are to this day. We would talk about it, but Leonard was discouraged about doing a book on cartoons because Mike Barrier announced that he was doing his own book in the pages of Funnyworld. But Barrier’s book, as you know, took 25 years to come out. After about a year, Leonard turned to me and said, “You know, I think we could do a book on animated cartoons. Let’s go for it.” We always felt that Barrier’s book was going to come out any minute while we worked on Of Mice and Magic. It was a weird fear we had, about that book that didn’t even exist!

Of Mice and Magic was really Leonards book, and I was his research assistant. I spent a couple of years in the 70s working on it and researching animation history, writing for Mindrot, that sort of thing. I derailed my plans to become an animator, and for a full-time job in New York City, I ended up working at United Artists for the next six years. That was a fortuitous thing for a lot of reasons. They had the Warner Bros. library, the pre-1948 Looney Tunes, the MGM cartoons, the Popeye and also the DePatie-Freleng cartoons. I ended up going to the 16mm rental division, and I got to watch pretty much the entire library. Thats where I learned film distribution, and, from that point on I was in the film business.

It was around that time that Don Bluth formed his studio, and United Artists picked up The Secret of NIMH. Our department needed images for Banjo the Woodpile Cat, which we had also picked up. I asked if I could have contact with the Bluth studio, and my bosses were really nice. They said, Hey, were calling up the Bluth studio! Want to talk to somebody there? So here I am on the phone with Gary Goldman; I told him I was a fan and that I thought what they were doing was great. They invited me out, when I was in L.A., to visit the studio. I did, and wound up becoming good friends with Don, Gary and John Pomeroy while they were working on NIMH. I became a booster and would go to Comic Cons and promote the film for them. UA also released, or rather didnt release, Rock and Rule around that time, so I got to meet Michael Hirsch and the people at Nelvana. Some of my best relationships started around that period.

Anyway, during the early 80s, with Of Mice and Magic published and me writing articles, I felt the path I was taking was historian. When we were working on Of Mice and Magic, Will Friedwald was assisting me. Now, I thought that Of Mice and Magic was going to be like The Great Movie Shorts, except that it would be about cartoons. I figured that after the chapter on Warner Bros. there would be a filmography, not all bunched up at the back like it was, and each film would include a one-line plot synopsis to tell you what that film was about. When Will and I were working on the filmography, we actually went a little nutty and started to add all the synopses we could. Leonard thought it was too much; he didnt think we could do a filmography. At the time, that stuff, that information just wasnt out there; it wasnt compiled.

So, Will and I had done something no one had done before; we compiled these filmographies. Leonard just didnt think we could do it. It was kind of like a dare! It seemed impossible then, and Leonard thought that even if we could come up with all of them, it would fill up too much of the book. Here, Will and I had a filmography, with all this extra information included. After Of Mice and Magic went to press, Will and I thought, well, lets use what weve got here and take at least one of the studios. Lets do Warners, since thats our favorite, and see if we can get it published somewhere. I was happy that people liked The Warner Bros. Cartoons, the original book we put out through Scarecrow Press, but I was never happy with it. In my opinion, it was unpolished and raw.

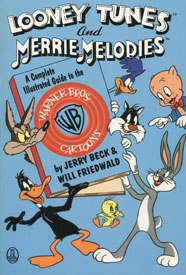

In 1989, we came out with the book I wanted to do, Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies. It took between 1981 and 1989 to finally get the revised version done. What I didnt like about the new edition was that it was very dry. Warner Bros did not want us to say anything negative about the cartoons; they just wanted to see a reference book. Since they were giving us permission to use illustrations, and access to their cartoon prints, I felt kind of obligated to go with that. Luckily, Chuck Jones, Bob Clampett Friz Freleng they were all still around in those days, really liked the Scarecrow Press book and went to bat for us with Warner Bros.

(I can only imagine being backed by Jones, Clampett, and Freleng! This must be something like batting ahead of Albert Pujols, Alex Rodriguez and Barry Bonds. Could it get better than that?)

In the meantime, I moved to L.A. and got involved with animation distribution with Expanded Ent. While I was there, I was involved with the creation of Animation Magazine, worked on animation festivals, and just became immersed in animation. Thats also when I started to do more books, like I Tawt I Taw a Puddy Tat and The 50 Greatest Cartoons. I co-created Streamline Pictures in the late 1980s, distributing anime. At Streamline, we did everything; we dubbed animation, distributed the movies, made the posters, did the trailers. We did everything a major studio does, only with a small staff, so I gained a lot of experience in the film business. My partner at Streamline was the infamous Carl Macek. Carl and I would operate Streamline during the day and do freelance work at night. In my case, that meant writing box copy for the collections of MGM/UA VHS cartoon tapes. That job really paid my bills during that time.

Carl was also working on a number of projects, one of which was teaming up with my friend John Kricfalusi. That was the beginning of Spumco. Believe it or not, Streamline and Spumco originally shared an office space on Melrose Avenue. While they were literally designing Ren & Stimpy in the same office, I was on the phone trying to convince theaters to play Akira. After Ren & Stimpy got going, Carl and John K broke up their partnership, but I stayed friendly with everybody and used to hang out at their offices. During the Ren & Stimpy period I thought, If I could only be an animator and do what these guys do! Ive always seemed to have friends in the business among the artists and animators. So I rooted for them. Ive always felt that animators need friends up in the executive suite, people like Linda Simensky and Heather Kenyon who know something about animation. Most executives dont.

(Heather Kenyon was my original editor at AWN, and I can tell you that Jerry is perfectly right. It would be hard to find an animation executive with more knowledge and passion than Heather. Thanks to her, my experience at AWN was as much an education as a wonderful experience.)

When the opportunity came to go to Nickelodeon in the Nick Movies department in the mid-90s, I took the job and felt, Maybe this is my role, because animators need friends on this side. Everyone who loves animation goes into it, and the people who love it the most are the ones doing it. But where are the people who really love animation in other parts of the distribution chain? If someone who truly loved animation were running Boomerang, or Cartoon Network or the Disney Channel, it would be a different kind of animal with a different kind of feel. Thats because someone who loves animation would be in charge.

For example, The Disney Treasures DVD are different because Leonard Maltin is involved. That is why the Looney Tunes Golden Collection sets are different, because of one person, Warner Home Video svp George Feltenstein. Hes not an artist, hes never wanted to be, hes a film buff who loves animation. People wonder, how come cartoon collection sets like this havent come out at Universal or Viacom? Because no one there cares! It comes down to the right person being in the right place.

(This comment rather made me wish that I had a pair of fairly oddparents.)

I left Nickelodeon Movies after three years and went to work for Disney TV animation, which did not last a year. I elected to leave because it just wasnt working out. I had an opportunity to develop classic Disney properties for TV series, but I got very frustrated because it became clear to me that they werent going to do anything that I suggested. You break your back coming up with concepts that you know are just not going to happen. Its very frustrating.

I had an idea called Mouseketeers; it was a whole new show using a Disney concept that seemed to be dormant. I developed it with my friend George Maestri, the guy who turned Matt Stone and Trey Parkers cutouts into a computer program for the first few episodes of South Park. He drew up some demented-looking South Park-ian Mouseketeers and animated them on computer. I thought it was cool, radical and edgy. We brought it in, and, well, that was the straw that broke the camels back. The thinking there at the time was so backwards. When I left Disney, I told George that we should take this Mouseketeers thing to other places. So, we took their mouse ears off and re-dubbed the characters as Karen and Kirby.

Things got very busy after that. We had Fox and Warner Bros. interested in Karen and Kirby, and we went with Warners for a year. I was the writer, producer, co-creator. We had an office at Sherman Oaks, where my friends were working on Batman Beyond. Richard Horvitz (Invader Zim) was Kirby, and my good friend Cheryl Chase (Rugrats) played Karen. We ended up being interstitials on The Big Cartoony Show in 1999. At the same time I was doing Karen and Kirby, I got the greenlight to do the Toonheads lost cartoons special.

After Karen and Kirby, George and I got a call from a company for some animators to do an educational project about teaching math. We went down to this cattle call along with Klasky Csupo, Film Roman and all these other reps from companies that came to audition. We went in with nothing but our Karen and Kirby samples and pitched ourselves. We got the job, and thats what started this little animation company called Rubber Bug. George and I wound up doing this production called Algebras Cool, 80, one-minute interstitials, and we were in production for a full year. I did the writing, with my old friend from my Harvey Ent. days (Jerry was an exec producer on The Baby Huey Show in 1994), Bill Vallely as my writing consultant.

Now we had a studio going and we started to develop other properties to pitch around. So, now the training wheels are off, and Im very proud of that. How Hornswiggle came about, and how it was pitched to Fred Seibert for whats now being called The Random Cartoon Show is another long story, but everything Ive done so far was really leading up to that point.

(Im rooting for Hornswiggle! This cartoon is styled in a nifty blend between Terrytoons [circa Gene Deitch] and the classic Looney Tunes. Its funnier than hell and done by veterans who really revere the art of making a good cartoon. To take a peek at Jerrys toon, visit the Hornswiggle! website.

Since I write a column about toons every month, I asked Jerry to give a bit of his philosophy on animation and how it should be presented to the public.)

Im still trying to further the idea that animation isnt just kids stuff. First with Looney Tunes and then with anime and also with books like Outlaw Animation. Once Of Mice and Magic came out, I saw a seismic shift happen, the public reaction start to change. People began taking cartoons seriously. Why? The original publisher for Of Mice and Magic was McGraw-Hill. They were textbook publishers, and they formatted the book like a textbook. Theres something about it that lends authority to the subject. Even the font and layout took the subject seriously.

That taught me a lesson: go serious and straight with it if you want credibility with the public. Cartoons are wacky enough; they dont need extra wackiness with the layout of the book. Again, treat the subject with respect and people will take it seriously. And thats why, if Im giving an on-camera interview, or a lecture, I dress as straight as possible. People who do interviews wearing a hundred pins, the bright green jackets and the big Bugs Bunny ties, they look silly. It makes us look like a bunch of wackos. The animation scholar should look like a scholar.

Martin Dr. Toon Goodman is a longtime student and fan of animation. He lives in Anderson, Indiana.