Directors Anna Samo and Lisa LaBracio discuss their TED-Ed short film based on the Brendan Constantine poem about the opposite to the word ‘gun.’

One of the challenges of making an animated film based on a literary source is finding the right balance between illustration and abstraction. And if you’re dealing with a loaded subject like guns (sorry), there’s the additional danger that you may wind up hectoring your audience and come off looking like a scold. It’s a significant accomplishment, then, that in The Opposites Game, filmmakers Anna Samo and Lisa LaBracio succeed not only in finding a visual style that is faithful to their source without being overly literal, but also in managing to express a point of view without crossing the line into polemics.

Based on a poem by Brendan Constantine (who also provides the narration), The Opposites Game was produced as part of the series There’s a Poem for That, which itself is part of TED’s youth and education initiative, Ted-Ed. In the film, a teacher takes a line from Emily Dickinson – “My life had stood a loaded gun” – and asks his students to find antonyms for each of the words, as a way of stimulating thought about poetry and meaning. When the students have trouble agreeing on what the opposite of “gun” is, it leads to open warfare, and ultimately to some significant and sobering insights into the nature of words and the world.

We spoke with the directors of The Opposites Game (which you can watch just below) about their path to creating the film, their unorthodox production process, and what it was like for them to deal with a highly emotional topic that’s so much a part of our contemporary reality.

“I chose this poem for a number of reasons,” said LaBracio, who’s been working as an animation director with TED-Ed for several years and was responsible for initiating the project. “I'm also a teacher, so this poem kind of spoke to me – being in a classroom where you start a game, a lesson plan, and you don't exactly know where it's going to go. The humor really spoke to me, but there's also this heaviness in broaching a difficult subject with your students. And Brendan maintains this balance between how he talks about something so heavy, but also manages to keep it playful and honor the voices of the students in his classroom.”

Then LaBracio called her friend Samo to ask if she wanted to collaborate on the project. It was an easy sell. “Lisa sent me the poem and, when I read it, I was just blown away by its beauty and by all the little moments,” Samo noted. “It was immediately clear to me that I wanted to be part of it. I knew it wouldn't be the easiest thing to do, but I was passionate about doing it.”

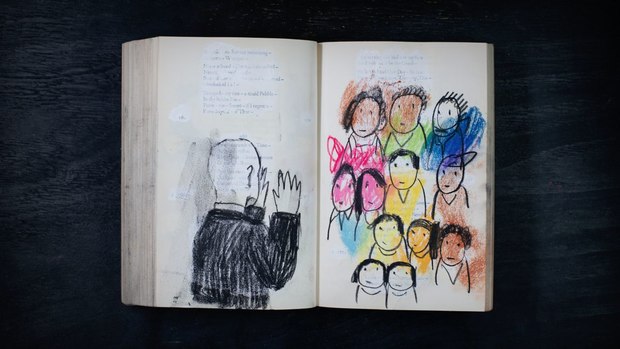

From the very start, they knew that they were going to “do something under the camera, something handmade,” because that was the animation technique they both most enjoyed. But how do you do justice to a work for which you have such high esteem? “Our first approach was that we talked about it a lot,” Samo shared. “We were talking, talking, talking, talking, on the phone, via email. We were searching for this ideal canvas. I didn't know anything about Emily Dickinson or her poetry, so I bought a really thick book of her complete poetry and took it with me on vacation.”

“And this kind of back-and-forth conversation ended up becoming how we worked,” LaBracia added. “Because we did actually work in two separate spaces. And we would take little segments of the poem that spoke to us and we would play under the camera with that. And so that's how the pages started getting whited out. But then that became part of the journey, because of Emily Dickinson’s poems. On one page it's like life, bees, flowers, life, life. And then the next page it's like death, death, death, death. So, we're writing the poems out and reading them as we're whiting them. And, looking back, we marvel at how that actually informed the entire production process.”

From start to finish, including two months of talking and initial tests, the production took about six months to complete. All of the animation was done by Samo and LaBracia using what the former describes as a “very unorthodox” pipeline. “We didn't follow this structure of making a storyboard and making the animatic designs and then animating,” Samo explains. “We would do some tests under the camera, then we would put the tests into Premiere Timeline with Brendan's voiceover. Then Lisa or I would go into Photoshop and do some quick storyboarding and import it into animatics, and then go back to the table and do some animation. So it was a constant back and forth, which felt very organic for animating the poem.” Both LaBracia and Samo credit Ted-Ed with granting them the freedom to work in this improvisational way and for providing great support throughout the process.

As far as dealing with the challenge of incorporating more abstract imagery into the narrative structure, it was – like the overall creative process – largely a matter of trial and error. “It was just this constant balancing act,” LaBracia described. “How do you show what he's saying without over-showing and without talking over him, without having our visuals overpower what the poem itself is trying to achieve? There were a lot of parts where it came naturally and others that really took multiple tries.”

Perhaps the most difficult part came at the very end of the film, which, like the poem, concludes with the line, “Your death will sit through many empty poems.” “The whole poem is building up to this last sentence,” Samo says. “And emotionally you understand exactly what it means, but you can't put it into words. So we were searching for a solution and we were also running out of time. And, really in an act of desperation, I cut in the moment where we white out the poems and it just clicked. It was this last piece of the puzzle that suddenly fell into place. These are empty poems and you don't have to say anything. This is just what it has to be.”

As LaBracia notes, this isn’t the first time they’ve had this kind of revelatory experience. “I mean, we've both been doing animation for years and, every time, there's always a hole in a project. And when you finally figure it out, you're like, ‘Wait, I've known the answer all along. Why am I tricked every time in this process?’ But it's kind of nice. It's fresh, it keeps everything feeling like a discovery for you.”