Read how the VFX teams rise to the challenge of enhancing a Universal monster classic.

Check out The Wolfman trailers and clips at AWNtv!

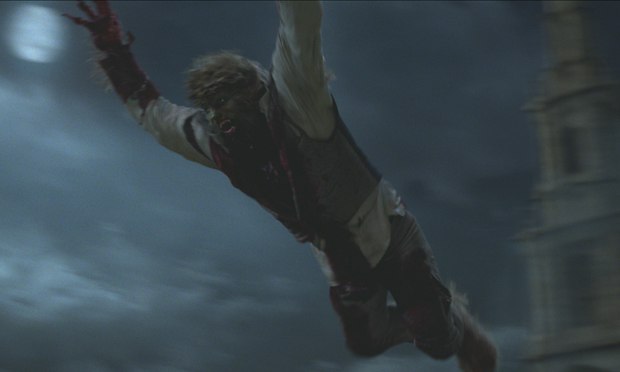

Despite its trouble plagued production, The Wolfman (produced by and starring Benicio del Torro) boasts some formidable vfx by lead vendor MPC as well as Rhythm & Hues and Double Negative, with additional support from Millennium FX, Peerless Camera and others.

After director Mark Romanek (One Hour Photo) departed over creative differences, Joe Johnston (The First Avenger: Captain America, Jurassic Park III) stepped in just prior to production. Steve Begg (Inkheart, The Golden Compass), the overall visual effects supervisor, was on the movie from the start, which lasted two-and-a-half years. He describes the challenging experience.

"The original plan was to try and blend Rick Baker's makeup design with CGI, which is what attracted me to the project in the first place," Begg explains. I thought we would continue that particular approach, but that's not quite what happened. It didn't automatically provide demarcation lines: it's one of those things that was organic. There wasn't a lot of planning in the visual effects work. I think that was courtesy of the fact that Joe had only three or four weeks before we actually started filming, so everything was ultimately biased toward a post-production approach. So the designing really occurred later.

I'd seen a lot of work by Rick Baker and his crew: the deformations and we took a lot of photographs and cyberscans of the artwork as a guide for us. Ultimately, what happened was we shot Benicio with tracking markers, reference cameras and the whole thing was basically invented in post-production. MPC was the primary company involved in all the transformation work, including the design and execution. And I have to admire the fact how it was designed on the run. We were given a selected cut of Benicio rising about, doing the mimicking, the potential transformation effects, and we overlaid the CGI (roto-animated, basically) on top of that. The whole thing was in a state of flux all the way through post-production from that point on. The movie was designed and finished about a year ago and then a reshoot was done around April or May to tie up some story points. So you're looking at year-old effects. So the rumor about the production being delayed by visual effects is not true. We worked on 1,200 shots and there are 600 in the film."

Indeed, MPC, led by Gary Brozenich and Adam Valdez, worked on fully animated Wolfman scenes, three gruesome transformations, all CG London rooftop scenes, enhancement of live-action Wolfman shots and the climactic waterfall environment.

"In particular, the transformation scenes required a lot of fresh ideas, trial-and-error and custom work to get what worked for Joe," explains Valdez in a prepared announcement. The transitions broke down to six painful stages, including expanding veins and skin bruising, hair growth and the visible change of muscle and bone. Cyber scans of del Toro were used as the basis for a fully articulated head rig, capable of going from the actor to a fully transformed Wolfman. Custom animation setups were built for hands and feet as well, then groomed with MPC's proprietary Furtility software, offering the ability for custom hair work on a per shot basis, in order to bridge live-action shots and obtain a perfect match to shots of makeup and mask enhancement. Many of these shots were extreme close-ups, requiring detail down to every pore of skin. Skin lighting and shading were pushed to the next level for this project, including new efficient methods for sub-surface scattering and fine specular modeling.

Full London rooftop environments were also created, using a combination of 3D architecture and 2D matte painting. Several different Victorian-era environments were entirely designed at MPC during post, in addition to the master shots looking over the Thames River, and a time-lapse shot located under London's iconic Tower Bridge. MPC's location in central London has proved invaluable for creating such environments via photogrammetric modeling from location shoots.

The 2D team led by Arundi Asregadoo consisted of projecting photography onto animated Wolfman faces and legs, enhancing live-action work. Not surprisingly, transformation shots came together in compositing, where artists tracked in fine veins and skin changes, based on texture work generated by MPC's fx department. Atmosphere was a constant issue in the film, with compositors blending in many photographic elements as well as simulated smoke and debris. And compositors worked closely with environment artists in a collaborative effort, using MPC's techniques for multi-layered 2.5D environment rendering.

Meanwhile, Rhythm & Hues was called on for 150 shots, including some last minute adjustments; namely, having the Wolfman go from biped to quadruped. "This was something we hadn't explored before and we had to literally hit the ground running," Begg continues. "It was quite difficult to make look real, and, in fact, was the trickiest sequence of effects in the whole film. The transformation is one thing: you know that's coming. But to make a tall humanoid shape go from biped to quadruped is quite difficult because the proportions of the legs are very strange. I think Rhythm & Hues solved that aspect quite heroically."

"The issue of running on all fours was challenging in that people have a much different relationship between arms and legs than dogs do between their forearms and rear legs," explains Derek Spears, visual effects supervisor for Rhythm & Hues. "The dogs' limbs are the same length and our legs are much longer than our arms, so we did a little shortening of the limbs in the quadruped mode. We actually had controls that could scale the length of the two leg bones to make them look more appropriate. So we took a little more of a compromise approach to find something that was a good match to what was already shot and to try and work a little more in a truly dog-like fashion. Another issue was dealing with attaching the feet, which involved tracking and integration. The environment was very smoky and hard to see and hard for the tracking people to get information and it was hard for the composite people to get integration. Rather than being restrictive, we let them shoot what they want and dealt with it in post."

For the running werewolf, they used their internal Voodoo animation package with the Wren renderer. "We started out with some motion capture," Spears suggests, "but quickly abandoned that and went to a fully-animated approach to get a more believable look."

Rhythm & Hues also did the big fight in Talbot Hall, which was done by stunt actors in tennis shoes with CG replacement of the feet and a few CG claw inserts.

But the biggest challenge was the fire simulation during that sequence. "The Fire sequence was done with clean plates, a fully animated character and CG flames," Spears continues. "The part I'm most happy with is the CG firework. It was completely simulated fire. We used Houdini as a base to run the simulations, and we have proprietary vector toolkit called Felt that we've used quite a bit, and we used that to make the fire more realistic. The results we were getting out of the box were too soft and a bit of a CG fire look to it, but we added a lot more detail when we brought it into Felt."

Double Negative, which worked on 350 shots spread across multiple scenes, was led by Visual Effects Supervisor Mark Michaels. This included the opening and the ending shots of the film, creating the iconic moon that is central to the theme, as well as some hallucination scenes. Much of the work, though, involved creating Talbot Hall. Filmed at Chatsworth House, it required much "disheveling" to create the director's interpretation. A dome was added to the top of the house, this was built as a CG model and the artists shaded and textured the lead on the roof and the surrounding stonework to match in. The dome was added to a number of shots and in a variety of lighting conditions, from daylight to night and even shots of the dome on fire, so the team needed to ensure that everything built was able to cope with the different set-ups. In 2D, led by Compositor, Jim Steel, ivies and vines were added to the front of the house. The vines were animated reacting to the wind and the team animated candle-light inside the house. The skies were replaced using digital matte paintings of moody overcast skies, which were animated in 2D.

In addition, Double Negative created overcast, moonlit skies to complement many of the exterior shots of the landscape and Talbot Hall. This was done as a 2D effect using cloud time lapse and stills photography, shot by Begg and Michaels; these elements were layered in 2D using 2D interactive lighting from the moon on the clouds. Matte paintings were created by Lead Matte Painter, Neil Miller and Dimitri Delacovias.

The R-rated film contains lots of blood and gore. One gruesome shot occurs where a character is impaled on iron railings, which had been filmed in camera, but a change in camera move, meant that the Dneg team was required to create a CG version of the entire plate and "massage" the performance of the stunt artist's fall to have more weight and impact. The stunt performer was replaced by a digi-double at the head and there was a projection of the stunt performer onto CG geometry for the tail of the shot. All of this was tied together with days of painstaking paint-work and the addition of 2D blood splurts.

"One thing that's missing, which is really sad, is that Double Negative did a beautiful color version of the original glass Universal logo for the title sequence and that dissolves into the moon and you tilt down into the forest," Begg offers. Dneg managed to procure the best scan possible of the original logo and then recreated it in CG for the update, first in black-and-white and then in color. This presented a significant design task to both the 2D and 3D teams.

Bill Desowitz is senior editor of AWN & VFXWorld.