Before there was TED, there was Eranos.

Once upon a time, there was a kingdom called Ascona. It was actually a town set on Lac Maggiore, straddling Italy and Switzerland. By the early 1930’s the town was equally famous for its quaint churches as it was for its bohemian, back-to-nature vibe.

For example, the villa of Mt. Veritas (Monte Verita) in Ascona became a retreat for artists and professionals who relished a respite from a scientific/logic-laden modernity that was blamed for social unrest. Nude bathing was encouraged, as was an individuality unleashed from norms held responsible for pushing the world into the post-War psychic and monetary depression. Artists such as Paul Klee, Otto Gross, and Hugo Ball were guests. So were Herman Hesse, Isadora Duncan, and Max Weber. And so was Sigmund Freud’s famous student, Carl Jung.

In 1920, a young widow arrived in Ascona. Olga Frobe-Kapteyn was born in London but educated in Berlin and Zurich. She studied art history, but also developed an interest in esotericism, spiritualism, theosophy, Jungian psychology, Indian philosophy, and the newly translated Yi Ching. After meeting Jung, she became inspired to surround herself with scholars researching the common roots and expressions of religion.

In 1928, Frobe-Kapteyn built a conference room near her villa. Legend has it that she hadn’t any idea why she needed a conference room, but in 1930, Jung suggested that she use the room as a “meeting place between East and West.” Rudolf Otto - the religious scholar whose seminal work on the profane and holy continues to inspire theologians - proposed she host an ecumenical, interdisciplinary conference called “Eranos.” (“Eranos” derived from the Greek for shared feast).

In 1933, the first Eranos conference was held. Under Jung’s tutelage, Eranos focused on a main theme. The first, on Yoga and Meditation in the East and West, featured invited speakers such as Heinrich Zimmer (renowned scholar of South Asian and Indian art and lore) and Carl Jung (by now departed from Freud, and forming Jungian analytical psychology). The primary aim of the conference was to welcome scholars to share and develop ideas on consciousness and the human psyche.

However, there was a darker side to these intellectual works. Pre-20th century Western understanding of consciousness and the psyche was in the domain of philosophy and religion. The early 20th century view on consciousness was dominated by Freud’s view of the human mind as having a consciousness dominated by a more powerful unconscious, a site of repressed memoires, desires, and fears (mostly concerning fears about our desires). Freud’s student, Jung, began to think of the unconscious less as the basement of individual trauma, and more of a repository for social and cultural memory. Jung termed this the “collective unconscious.” Jung viewed the process of psychic individuation, how the individual reconciles “self” and “social” identity, as a lifelong struggle and the core of human development.

About the same time as Freud and his students (including Jung) were grappling with understanding individual consciousness, the fields of cultural and social anthropology were developing. While many anthropologists were inspired by pure interest in understanding different cultures, many scholars were still influenced by theories that sought to establish superiority of civilizations, cultures, races and ethnic groups.

In 1933, when Eranos held its first symposium, King Kong was Hollywood’s reigning blockbuster. The movie screened widely, tapping into Western culture’s fascination with the exotic “dark continent” and unspoken (or often fiercely voiced) beliefs that these “uncivilized,” “primitive” cultures were psychologically inferior. Natural history museums of the time hosted “human zoos.”

And by 1933, the National Socialists had already taken root in Germany. Professors and scholars were dismissed, and books were burnt. To be politically correct in Nazi Germany (and soon most of Europe) was to be a racist.

But this is where things get weird. In 1934, Frobe-Kapteyn invited Martin Buber, the Jewish theologian and philosopher, to Eranos. In 1938, when Germany annexed Austria, Heinrich Zimmer and Carl Jung spoke on the archetype of “The Great Mother.” In 1939, Richard Thurnwald, the Austrian anthropologist, and Louis Massignon, scholar of Islamic mysticism, joined the table. This was one month before Germany invaded Poland.

In fact, Eranos continued all during World War 2. It was as if there was a magic circle around Olga’s round table. Out of idealism, ignorance, indifference, or collusion, the speakers continued to bring intellectual offerings to the dinners.

In one of the few detailed books on the history of Eranos, (“Eranos: An Alternative Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century,” by Hans Thomas Hakl, Christopher McIntosh, 2014, McGill-Queen's Press) the authors describe how Frobe-Kapteyn may have made deals with the devil to continue the lectures during the War, although the authors also claims that the Nazis themselves didn’t quite know how to deal with the very existence of the conference. At the same time, some of Jung’s writings during the 30’s on race, religion, ethnicity, racial purity, and unquestioned nationalism are odious and inexcusable.

But Jung was also known as “Agent 488,” one of the important informants to Allen Dulles, the OSS chief in Switzerland during WW2. According to Dulles, who became the CIA’s first civilian director, “Nobody will ever know how much Jung did for the Allies during the war.”

We do know that Heinrich Zimmer, who was Lutheran, left Germany to save his Jewish wife. In fact, Zimmer’s lectures at Columbia University inspired one of his students to develop his teacher’s ideas and carry on the work of comparative mythology; Joseph Campbell translated Zimmer’s work as well as the early yearbooks of the Eranos Conference during the war years. Campbell attended the Eranos Conference first in 1953, and presented there in 1956, and the rest is film history (or myth). (Anybody want to make a movie out of this? You can hire me as the researcher ;-)

Most film buffs know the mythmaker backstory to Star Wars. George Lucas, former anthropology student, credited Joseph Campbell as a mentor in helping him generate much of the mythic structure of the story. Bill Moyers interviewed Campbell extensively in 1988’s The Power of Myth, mostly filmed at Lucas’ Skywalker Ranch. The series covers many of the motifs that myths universally appear to have, and Campbell refers to scholars in early 20th century psychology, comparative religion and language who influenced his journey. In particular, he mentions Carl Jung and Heinrich Zimmer, as essential to his own ideas.

So the complicated history of the Eranos Conference raises some interesting questions: To what extent does the viewer separate knowing about the artist from experiencing the artwork? Could we or should we judge an idea separately from its creator?

From a cognitive perspective, the issue is complicated. For example, when asked whether a painting is “liked” (a subjective comment on the viewer’s feelings), viewers were influenced more by artist intention or process than if asked if the work was “good” (a more objective judgment based on the formal features of the work itself). http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0070759

So does knowing the racist/homophobic/misogynist beliefs of the artist/author/scientist discredit the work?

--

For more on Eranos:

http://www.eranosfoundation.org/history.html

Image Credits:

The Eranos Round Table.

The view from Casa Eranos, across the Lago Maggori to the Italian Alps.

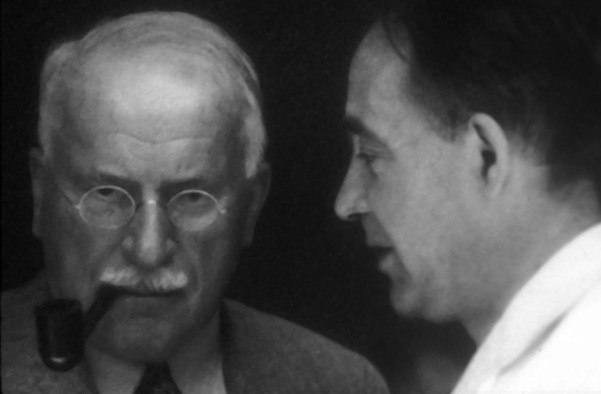

Jung and Zimmer, Joseph Campbell’s mentors, at the 1936 Eranos.

Joseph Campbell, Jean Erdman his wife, Hull and his son Jeremy in Ascona, 1953.