The Oscar and Emmy Award-winning filmmaker, author, and illustrator shares how a series of tragic losses – first his young daughter, then his wife – led to a prolonged period of creative withdrawal that he eventually emerged from, due to a simple twist of fate, to produce some of his career’s strongest and most innovative work.

When it comes to contemporary creative powerhouses, it’s hard to top William Joyce. There’s “prolific,” and then there’s the Shreveport, Louisiana native. He’s written and illustrated more than 50 bestselling kids’ books, including “Rolie Polie Olie” - made into a pioneering CG animated, Emmy Award-winning animated TV series - and “The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore,” made into an Oscar-winning animated short film. His 2016 book, “Ollie’s Odyssey” was adapted by Shannon Tindle and Peter Ramsey into a compelling four-part miniseries, Lost Ollie, now streaming on Netflix.

His animated feature film work is equally extensive. He created conceptual characters for Pixar’s Toy Story (1995) and A Bugs Life (1998), and created, produced, and served as production designer on Robots (2005) for Blue Sky Studios. At Disney, he executive produced, wrote script drafts, and did design work on Meet the Robinsons (2007), a feature adapted from his book, “A Day with Wilbur Robinson.”

But as he began work directing another of his book adaptations, Rise of the Guardians (2012) at DreamWorks Animation, Joyce suddenly found himself reeling from a devastating succession of tragedies that included the loss from terminal illnesses of his young daughter Mary Katherine in 2010 and his wife Elizabeth in 2016. Though he somehow managed to write, production design, and executive produce Epic (2013) at Blue Sky, he soon retreated, focusing his energy on caring for Elizabeth through her final years.

Her passing was followed by years of creative withdrawal, Joyce too emotionally and physically drained to return to the world of entertainment he’d so successfully graced for so many years.

But, as Joyce reveals, his destiny was far from sealed. Resigned to living out life on his own, he was introduced to a woman, Hilary, whom he refers to as an “unexpected ray of hope.” They grew close, eventually married, and he emerged from his seclusion to reconnect with David Prescott, who had just joined DNEG Animation as Senior VP Creative Production. Together, they put in motion an animated feature, The Great Gatsby. But first, they decided to mix things up a bit and kick the tires on using Epic Games’ Unreal Engine to produce an animated short.

That film, Mr. Spam Gets a New Hat, written and directed by Joyce, epitomizes the idea of “hope,” a highly personal story of a man whose dreams are literally beaten down each day as he’s repeatedly hit on the head by a hammer at his job in a hat testing factory. But after meeting a beautiful artist and dreamer who opens his eyes to a world of possibilities, he breaks free from his relentlessly gray life to embrace a new world of color.

Inspired by the silent films of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, and designed with a classic Technicolor look, Mr. Spam Gets a New Hat parallels Joyce’s own journey from the overwhelming and emotionally crippling losses that he could have so easily – and understandably – never moved past.

In a sprawling, insightful and thoroughly enjoyable hour plus interview, edited for publication, Joyce shared his harrowing story, how Mr. Spam took root, how Unreal Engine opened up a new, exciting world of filmmaking he never wants to leave, and how fate often intervenes in ways you least expect.

Take a few minutes to enjoy Mr. Spam Gets a New Hat – here’s the link - before learning more about how this charming film was made.

Dan Sarto: This film is a throwback to the age of silent films. So subtle, so nuanced, yet quite emotional. It’s also obviously quite personal. I understand it came about after a period of tremendous loss. Can you share how the story and production with DNEG came about?

William Joyce: Well, it started out a long time ago. I was talking to my lawyer one day and I asked him if he liked being a lawyer. And he said, “I would rather be hit on the head all day with hammers than practice law.” And I thought, “That's a pretty dark image.” And that stuck with me… I was like, “One of these days I'm going to write a story about that.” For ages, it tumbled around in my head… this little guy who wears a derby hat and gets hit in the head by hammers all day. And he can't take his hat off. That's all I had. I didn't really know why he was being hit in the head all day, but it became an allegory to me for people who hate their jobs.

It stayed there for years, tumbling around, tumbling around, tumbling around. And then my daughter Mary Katherine became ill when we were making Rise of the Guardians [2012], and soon after she passed, my wife Elizabeth was diagnosed with ALS and began a long tragic decline, and that's all I really focused on. I didn't work very much in the sense of preparing new projects. Rise of The Guardians came out after Mary Katherine passed away. And Epic [2013] came out during the worst of everything.

I'd made [The Fantastic Flying Books of] Morris Lessmore [which won the Oscar in 2012] in which I used tragedy to explain to myself my feelings. What happens a lot of times is these stories come out of whatever's going on in my life. They help me understand things. It's not like I sit down and go, “Here's my checklist of things that are baffling me about the universe and I'll tell a story to come to grips with them.” The story just starts coming out and subliminally it's touching on those subjects.

My wife’s illness was so difficult, so all consuming. She lived here at home. I promised her that she wouldn't spend her final days in a hospital. She slowly but surely lost her ability to speak, to move, and was paralyzed and couldn't breathe on her own. And she's like, “I don't want to spend the last part of my life in a hospital, that's just too depressing.” And I'm like, “Baby, that will not happen.” We built this whole mini hospital here in the house to take care of her. We had a staff of five nurses. Her prognosis was 18 months and we made it work for five years. She wanted to see our son graduate from high school and go to college. She wanted to live that long. We got all the way through college… she knew that he had graduated.

And after my wife passed away, I just sat around, kind of droopy, for about two years. Just sat in the kitchen. I didn't try to think of a story. I didn't think, I was just so tired. It was incredibly rewarding to help Elizabeth for all that time and to take such good care of her because she really wanted to live. She wanted to be there for our son. And we learned to communicate in a completely nonverbal way. She had this screen, like Stephen Hawking, where you type out what you want to say with your eyes, but it was very cumbersome and slow. Whenever they filmed Stephen Hawking using it, they edited it down a lot because it takes a long time.

But we got to a point where we knew the realm of things that were common to her needs, and I could read her expressions. It was the most miraculous thing. She would just radiate subtle messages and I would get it; I could understand with specificness that was remarkable. Not just me but my son and the nurses. It made me think a lot about silent movies and how beautifully they can convey emotion and dialogue with almost nothing, right?

DS: Very much so.

WJ: But that didn't all click in until [I got together with] David Prescott. He and I had worked together on Guardians. Early on when I was directing it before my daughter got sick and Elizabeth got sick, Dave and I did a lot of really exciting exploration in how to use game engines to make things go faster in animation. To make storyboarding and layout more organically entwined so that you could set up your shots in a way where you knew where the location was, and you could build the set rudimentarily and think about where the characters should be within that scene… building that in the game engine with a pretty amazing level of sophistication.

That was 12, maybe 13 years ago. We could guide the storyboard artists, like, “This is where everybody stands, you go screen left.” It took away so much of the guesswork that can slow down storyboarding, so you can concentrate more on performance. It was awesome. So, we’d been talking for years about exploring that further.

He called me, I guess it was just before the pandemic, and said, “I've landed at DNEG, and it seems like the place where we can play with game engines. So, what do you want to do?” I said, “I want to make The Great Gatsby into an animated feature film,” which is nuts. And he goes, “Ah, love it. Let’s start figuring out how to do that. I want to use Epic Game’s Unreal Engine. We're partnering with them on some R&D.” And I go, “That's brilliant, but let's not do Gatsby first. Let's do a short film first and try it out. Find out what the bugs are and try to push the style that we want for Gatsby in a small form project.”

DS: Sounds reasonable.

WJ: Indeed. We didn’t want to get bogged down on a bunch of, “Oh my God, everybody looks terrible. We're too close to the Uncanny Valley. My God, it looks terrifying.” Let's take a big step forward, but not all the way there. Let's see what can happen if we try to get two-thirds of the way there. Let’s try to replicate old Technicolor and make a silent film.

I couldn't get that out of my mind, how beautifully my wife and I could communicate without words and yet understand exactly what was going on. So, David's like, “All right… God, William, it's like Gatsby's crazy, but this is even crazier.” And I'm like, “It's not because it's a short film.” And he goes, “You're right.” So, we went for it.

I told him the story, which now had what it didn't have before. There’s a man named Spam – yes, his name was always Spam. The day my lawyer told me he would rather be hit in the head with hammers all day than be a lawyer, the title came into my head… Mr. Spam Gets a New Hat.

But something else had happened since that day. After my wife passed away, I really thought that part of my life, the romantic part of my life, was over. I didn't have any interest in being with anybody else. I figured, I'm going to have this quiet little life, my son is graduating from school, he's going to be an artist, he will go on his way, and I will cobble away on my stories and that's the life I'll have. But every time you think you know you've got everything figured out, that's when fate decides to shake you up a bit.

A friend of mine introduced me to this lovely woman named Hillary… she's just gone through a divorce, and I think you guys could be good for each other. You both went through a really tough thing. And I was like, “Okay.” We’re going to meet… our friend would be there with us. It ends up we both had a secret code that we could use to let our friend know we weren’t interested. So, we sat down with our friend Judy… but neither of us used our code. We just kept having fun. And then we fell in love. And that's when I really got to start my life over. My dreams started coming back, and I started working again. I raised some money to develop ideas and for the last three years I've been working on those, doing visual development and test animations, having scripts written. And I did this short with David, DNEG, and his wonderful crew bringing Mr. Spam to life.

I didn't know how sad I was, how I had given up on hope, but hope apparently had not given up on me. And so, getting to do this short film brought all this stuff into focus and made me understand how I'd been feeling, what I'd been going through. And it was very important for me to get it right.

Hillary and I got married… and she is Dot, the girl in the movie, and I am Mr. Spam, who we made considerably younger and more handsome.

DS: Creative license.

WJ: You know, you make movies. It's your reality.

DS: What did the Unreal Engine platform provide you on this film creatively that you haven't had before? What were you able to take advantage of as a filmmaker that you haven’t been able to previously?

WJ: Almost everything, and I mean that. As you said, this seems like a simple short, but there's a lot going on. There's 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 human characters with very sophisticated rigs and very sophisticated design. They're deceptively simple. We looked at Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton a lot. We looked at Harold Lloyd a lot. We looked at Cary Grant a lot. Cary Grant was an extraordinarily funny physical actor when he wanted to be. He could be that handsome movie star guy, but when he went into silly land in Bringing Up Baby [1938] or Arsenic and Old Lace [1944] … if he had been a silent film comedian, he would've been as revered as Keaton and Chaplin. He had that sense of his physical self and how to modulate a pose that was just perfect animation fodder. He had a sense of timing and movement and literally what keyframe to strike.

So, in designing these characters, we paid great attention to that. We designed the rigs to take advantage of those things, the subtleties, and the broadness. Keaton kept his dead pan through the most catastrophic events. His body would experience wild things, but his face would remain placid. And Chaplin, when he was out to convey poignancy at the end of City Lights [1931], it's such subtle acting. And so, it's like, “Okay guys, we have these tools, and we have this rig, and we can dial it up to 11, it can be very broad, but keep it at 2 most of the time.”

Watch these [silent film] actors. They wait, they hold it before they explode, and that's what makes it effective. And when they go in for emotion, they do so little expressively, and things get still and quiet… it pulls the audience in like no other kind of filmmaking does. And so, we're able to build those rigs faster. We're able to get to our final designs faster, but that was just the beginning of great things with Unreal.

David asked, “What is it you've been missing in animation? What's the bottleneck?” And I'm like, “It's what we've always talked about. Pinning up storyboards for a year is fine, but I want to be able to help the storyboard artists know what the set is, what the blocking is, so they can concentrate their drawings on the performance.” So, we built our sets. Remember, it’s a short film. It's not like a three-act feature film. We know exactly what we're going to have. All of a sudden, we're not going to say the third act doesn't work and throw everything out. We've got a pretty good idea what we're going to build and if things aren't working, we'll figure out a way to make it work within the confines of what we built because we don’t have a choice.

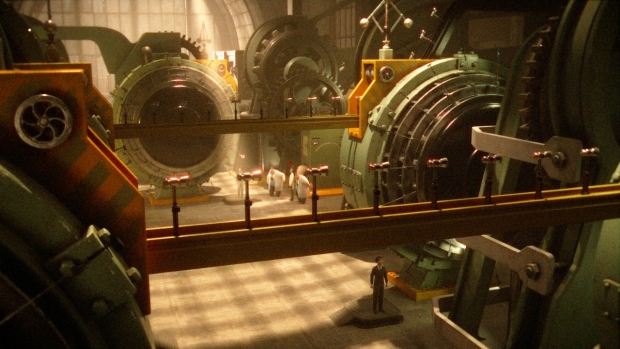

We built our sets in considerable detail, even before we were storyboarding, so by the time we were storyboarding, I was able to go into lit virtual sets with a camera crew. It wasn’t the gray death zone of layout. They were lit. Not perfectly, but they were lit 50% of where they were going to end up. We would even talk about that beforehand. What time of day is this scene? What's the weather? What is the mood? And they would have that set lit for me rudimentarily, but very evocatively. And I could say, “Okay, he's coming into work and he's in a good mood, but the giant mechanics of this place are all there to bear down on him” as you see all this stuff in the factory. But slowly, things will change. The whole giant set of that awful factory was going to come to bear on him.

Now, I'm working in Shreveport, Louisiana. It during the pandemic, everybody's in lockdown. I can't go to London… I can't meet the team. They're in lockdown, they can't leave their apartments. And yet, there we all are, wherever we’re at, looking at screens wherever we are, and we're able to conjure up within a nanosecond of me saying, I want the camera to be here and bam, it's there. And I'm like, “Can you Dutch it a little bit? Bam, they Dutch it. Can you toggle it up just a little? I want to get more of the ceiling in there. Bam. It's there. And I'm like, “Okay, that's the shot. Take a screen grab, give it to the storyboard artists and we'll be able to tell them who's standing where.”

Not only did it help with storyboarding, but it helped us “see” the scene. It helped us to know early on the limitations that the set may have, so we could change things to accommodate the storytelling, change the layout of a set so we could do the blocking just a little bit different. That's never happened before. It was more live-action filmmaking. It was like I was going onto my set with my cameraman and saying, “Here's where we're going to put our shots,” like you do in live-action. We had a clarity, right? And a certainty that this is going to work. Then we'd start to put the characters in. And it was so exciting.

My first animation reviews on the lit set were actually too much. It was like, “I can't concentrate on the performance. I'm looking at the leaves… how really nice they look over there, maybe we should move that shadow.” It was like, “Can we go back? Can we go back? You made it look too good!” And they did. But they started slowly slipping the details back into the set, fully lit. And I got used to it. There were times when the storyboard artists were saying, “we're getting too much information, it's messing us up.” And I'm like, “Okay, then just draw and we'll figure it out later.”

DS: So, you’re saying that the storyboard artists were looking at lit animation too early, that there was too much to look at visually that you had to back out the level of details? It sounds like that was fundamentally a completely different filmmaking experience for you.

WJ: Absolutely. Absolutely. But then you get used to it. You learn to adapt to it, and you learn to adapt it to what works best for you. That's one thing that's so remarkable about the experience with Unreal. It didn't come with any set rules. It was like, “Well, let's do this, let's change that.” And then, when we got into making the film look like old Technicolor, that's when it became really interesting. I really wanted to replicate Technicolor, which is a lot more difficult than you'd think. We studied Technicolor, all the peculiarities and alchemy of it because it really was a nearly alchemic magic process with all these inks. And we replicated it so well that we started having the same problems that Technicolor had in its early days with [actor] makeup.

Old Technicolor would respond to different colors bizarrely, like reds would turn gray. When we started doing our first Technicolor renders, people looked washed out and gray. Anything red looked kind of gray, so we had to really tinker with the reds the same way they had to when they were making The Wizard of Oz. Max Factor had to invent this new kind of makeup that would respond to Technicolor correctly, so people didn't look like crypt keepers. It's really funny to see how crazy the makeup was on these actors when they were walking around the set being photographed in regular color, not Technicolor. They look so peculiar. It must have been hard to act, to give a performance, to sit there with Vivien Leigh and Clark Gable looking each other and they almost look like Lily and Herman Munster.

They had you put some green into the red to make it look red. We had the same problems. It was so awesome. I felt like, what a geek. We created it so well that we're having to deal with the same issues, like the level of film grain and saturation of color. Remember, Technicolor was three strips of film that laid on top of each other as they went through the projector. So, they were never in perfect registration. There was always just a little bit of waviness going on. And we realized if you didn't put that in there, it didn't look like old Technicolor, it didn't have that dreamy never quite all the way in focus quality. It was always shifting.

When you watch old Technicolor, it's so alive because it's changing constantly. There's no uniformity to what's going on. So, it feels like reality removed. It simplifies reality. It takes away probably a fourth of the detail of things, the reds around the edges sometimes. It's all these weird little things that you notice when you watch one of those old movies. I love the way this looks. But it doesn't look like Earth, it's like an imagined Earth, right?

DS: Right.

WJ: It's several degrees removed from our reality. And I really wanted to try to recreate that look. And it took the power of Unreal Engine to handle all that data.

DS: You certainly captured that imperfect look perfectly in the finished film. And the visuals are much more sophisticated than may appear at first blush. But ultimately, you told a sweet, gentle story so delicately and emotionally.

WJ: Thank you.

DS: I recently talked to Mark Andrews about his new series, Super Giant Robot Brothers, also produced in Unreal Engine, and he echoed much of what you’ve been telling me. He never wants to go back to the old way of making animation. With Unreal, he’s not just an animation director, he's a filmmaker. He doesn't have all these production silos working sequentially in an animation pipeline. He's in the virtual world with the camera and if he wants to see something different, the team can put something together quickly, get someone out on a performance capture stage in a few hours and they've got more fully animated and lit takes for a scene. He said this is unprecedented in his entire career. And it sounds like you're saying the very same things.

WJ: I don't ever want to go back. This is all too exciting. It makes animation much more intuitive and immediate and that's a gigantic difference for me. You don't wait for weeks to see what something's going to be like. You can see it right then.

DS: From a creative standpoint, you have much more control.

WJ: Completely. It's just fantastic.

DS: William, it’s been such a pleasure speaking with you. Thank you so much.

WJ: Great talking to you too Dan.

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.