Jim Korkis chronicles Walt Disneys work in commercials during the 1950s when the best-loved ads were animated.

As Brer Rabbit tries to escape from Brer Fox and Brer Bear, he finally finds his laughing place in the inside of an American Motors car with all season air conditioning. Tinker Bell rescues Captain Hook from being eaten by the crocodile by flying in the nick of time with Peter Pan Peanut Butter; it certainly is true is the favorite of people and crocodiles too. Pretty Alice in Wonderland with the voice of Kathryn Beaumont informs folks that, for energy, for color or just playing games, there is nothing quite like Jell-O.

Is this an alternate animated Disney reality or a sinister synergy scheme by modern Disney executives? Actually, it is a fascinating story of Walt Disney himself and the world of television commercials in the 1950s.

In the 40s and 50s, almost all television ads were presented live, and were often just talking heads describing products. Animation was expensive but advertisers soon discovered it was also highly effective and many of the best-liked ads were animated.

Former Disney artists, including David Hilberman, Zack Schwartz, Shamus Culhane, Grim Natwick and Art Babbit, did television animated commercial work starting in the 40s. Preston Blair told animation historian Karl Cohen that he felt like a race horse tied to a milk wagon. I wasnt exercising my full potential at all.

The 50s were a peak period for classic television animated commercials with the creation of memorable animated stars from Speedy Alka Seltzer to the Hamms Beer Bear. The 50s were also a time of renaissance at the Disney Studio that was still recovering from the financial hardships of World War II. While Cinderella had been a success, Walt was desperately in need of money to help maintain the studio and to finance his latest project, the worlds first theme park to be called Disneyland.

Walts Secret Producer

Walt had already drawn the ire of other movie studios for his agreeing to produce original programming for the enemy of television that was stealing audiences from theaters. To produce television commercials was considered so beneath the status of a major movie studio that it was unthinkable. However, Walt had a plan to tap into that lucrative area and it included the use of someone he knew he could trust: a close relative.

Phyllis Bounds was the wealthy niece of Walt Disneys wife, Lillian. According to animation historian John Canemaker, she was hard-drinking, hard-smoking, artistic, stubborn and opinionated. She was married five times.

Her third husband was George Hurrell, famous for his glamour photography of movie stars in the 40s. Hurrells style of photography had fallen out of fashion by the 50s and he and Phyllis started their own television production studio, located on the Disney Studio lot, to produce advertising utilizing the Disney staff. Started in 1952, Hurrell left the studio and returned to New York two years later leaving Phyllis as the TV commercial co-coordinator from 1954-1957. Officially, the Disney Studio was not producing the commercials, but this independent studio that happened to be on the Disney lot was.

Big Money for Disney

Disney veteran Harry Tytle, who worked at the studio for more than 40 years in a variety of capacities including producing the weekly television program stated in his autobiography: Commercial work answered our prayers, as it supplied badly needed capital. Advertising work clearly helped keep the studio intact. But while the studio made money with this type of product (and I mean big money) it was not a field either Walt or Roy were happy to be in. Their reasoning was sound. We didnt own the characters we produced for other companies; there was absolutely no residual value. Worse, we were at the whim of the client; at each stage of production we had to twiddle our thumbs and await approval before we could venture on to the next step.

The Disney Studios produced two different tracks of commercials. First, they produced commercials featuring the classic Disney characters primarily for sponsors of the Disneyland television program like American Motors and Derby Foods. These commercials featured the classic Disney animated characters including Mickey Mouse, Pluto, Donald Duck, Tinker Bell, Jiminy Cricket, Alice and the Cheshire Cat and many others.

Second, Disney produced commercials for a variety of other accounts, often creating memorable new advertising character icons from Tommy Mohawk for Mohawk Carpets to Fresh Up Freddie for the 7-Up soft drink.

Disney Talent Goes Commercial

The primary director for these commercials was Charles Augustus Nick Nichols. Nichols, who began his Disney career as an animator on the Disney shorts, had most of his responsibility as a director on the Pluto cartoons from 1944-1951.

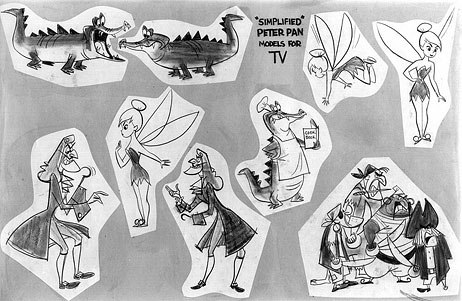

The commercials provided work for some of the Disney animators who had been working on the short cartoons that were being phased out of the theatrical schedule. Phil Duncan, Volus Jones, Bob Carlson, Bill Justice, Paul Carlson and others contributed to this new endeavor. Tom Oreb designed stylized versions of the Disney characters that were reminiscent of the work being done by UPA.

One of the greatest Disney storymen of all time, Bill Peet, remembered when he butted heads with Walt Disney on a segment of Sleeping Beauty, that the next day, I was sent down to the main floor to work on Peter Pan Peanut Butter TV commercials, which was without a doubt my punishment for what Walt considered my stubbornness. I toughed it out for about two months on peanut butter commercials, then stubbornly decided to return to my room on the third floor whether Walt liked it or not.

The commercial work also provided jobs for other talent at the Disney lot. Sterling Holloway and Cliff Jiminy Cricket Edwards narrated Peter Pan Peanut Butter commercials. Tinker Bell was mute in those days and had to pantomime her delight at the peanut butter that could be put on hot toast because it melted like butter and was so smooth that it could even be spread on crispy potato chips.

Edwards also performed as Jiminy Cricket and sang an adaptation of When You Wish Upon a Star for a Nash Rambler car commercial as well as being the spokes-cricket for Bakers Instant Chocolate Flavored Mix where he was in charge of Jiminy Crickets Sipping and Singing Society.

Kathryn Beaumont recreated her role as Alice in Alice in Wonderland in a series of commercials for Jell-O including one featuring the characters of the Griffin and the Mock Turtle. Jimmy Dodd, the Big Mousekeeter on the Mickey Mouse Club show, not only narrated commercials for Ipana toothpaste, but his sped-up voice was used for the character of Bucky Beaver singing Brusha Brusha Brusha. Use the new Ipana. There was a promotion where users of Ipana toothpaste could send in for photos from the Mickey Mouse Club.

Nothing Does it Like 7-Up

Besides Bucky Beaver, Disney also produced icons for other companies. Fresh Up Freddie was the mascot created by the Disney Studios for the 7-Up soft drink company. He was a cocky animated rooster who looked like a mixture of Panchito the Mexican rooster and the wacky Aracuan bird who both appeared in The Three Caballeros. Freddie demonstrated how to plan successful parties and picnics by having plenty of 7-Up on hand.

He spouted phrases like Fresh Up with 7-Up and Nothing Does it Like 7-Up. Freddie was supposedly named in honor of 7-Up bottler Fred Lutz Jr. Merchandise included a Fresh Up Freddie plastic doll, a Fresh Up Freddie Ruler, a pinback button and a Fresh Up Freddie Stuffed doll. Many of these items pop up in eBay auctions today.

They (7-Up) spent two and a half million dollars on their TV commercials, remembered Paul Carlson, who was Nichols assistant in the unit, when he talked with animation historian Michael Mallory. I think they did 26 one-minute commercials at $100,000 apiece. And we usually handed out the animation to the staff artists at Disney, but they would do the work at home.

Tommy, Minnie and Chatter

Walt signed a contract in 1951 to produce a series of eight animated commercials for Mohawk Carpets. The contract refers to the character as Tommy Hawk, but was finally named Tommy Mohawk. He was a young Indian boy with a Mohawk haircut with a feather and carried a tomahawk. The spots themselves were all animated in 1952.

The titles of the commercials from the Disney production files were: Tommy Tests Carpets, Tommy Supervises Weaving, Tommy Plants Carpet Seeds, Tommy Designs Carpets, Tommy Falls for Minnie, Tommy Gives Animals Sleeping Carpets, Birds Use Waterfall for Loom and Tommy Harvests Carpets.

Besides Tommy himself, the commercials featured his demure Indian maiden friend, Minnie (short for Minnehaha) and a mischievous squirrel known as Chatter who looked very similar to the character of Dale from Chip n Dale, but with a smaller nose and a squirrel tail. He also wore a plain headband and a single feather and the oversized headband keeps dropping comically over his eyes.

Officially the Disney Studios closed its television commercial division in the late 50s although it would still occasionally dabble in the commercial world in the following decades. The success of Disneyland and Walts frustration at struggling with commercial clients sounded the death knell for this interesting anecdote in the history of the Disney Co.

Jim Korkis is an award-winning teacher, a professional actor, magician and a published author with several books and hundreds of magazine articles to his credit. He is also an internationally recognized Disney historian whose research and writing has been used by the Disney Co. on many projects. He is a founding member and contributor to Walts People, a critically acclaimed series of books reprinting interviews with people who worked with Walt Disney.