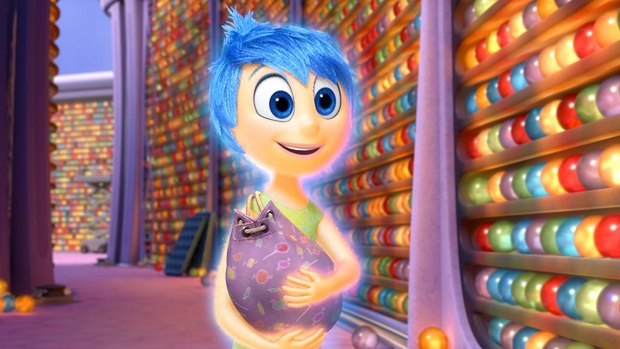

Co-director of Pixar’s Oscar-winning animated feature ‘Inside Out’ discusses the “Pixar Way” of patience and trusting the process.

Speak to enough people at Pixar, especially senior creatives, and sooner or later they sing the praises of Ronnie del Carmen. Clutching their Oscars backstage at last month’s Academy Awards, Pete Docter and Jonas Rivera were not shy when expressing their feelings on his importance to Inside Out and other Pixar films, with Rivera proclaiming, “He is an essential part of this movie. He contributed so much to the emotion, the heart of the movie, and we are incredibly lucky to work with him,” and Docter adding, “Ronnie is one of the great visual storytellers in animation.”

The film’s Oscar night win culminated a six-year journey that started with Docter’s first observations of his daughter’s suddenly sullen disposition. Del Carmen’s was right there the entire time, lending his talents as co-director, writer, storyboard artist, story editor and sounding board, working diligently to help Docter distill years of tumultuous development into a story finally worth producing, just like he's done with other Pixar directors on films like Monsters University, Brave, Up, Ratatouille and Finding Nemo.

I had a chance to attend del Carmen’s keynote presentation at SIGGRAPH Asia 2015 in Kobe, Japan this past November. We spoke at length afterwards about his work on the film and his thoughts on Pixar’s process and the inherent difficulties of fashioning good stories into animated films.

Dan Sarto: In speaking with you, Pete Docter, Jonas Rivera and Ralph Eggleston, you’ve all described the long, arduous path taken to make Inside Out. You wrote and rewrote and rewrote the story over a number of years before you were satisfied. I’m still amazed at how a top team of talented artists can get so far down the road on a production and come to the conclusion they don’t have a movie yet, that it’s not strong enough. How does that happen?

Ronnie del Carmen: There isn’t one set of circumstances that can make you either stop or go forward in a movie. Story has a certain kind of mystical quality to it. The only reason I say mystical is because there's no way to quantify or qualify that when you're making a left turn, you shouldn't be taking that turn, or when you're feeling like this is the right thing to do and you don’t stop until you get to the finish line. I've had experiences where a movie is going so well, from all aspects, by everybody's measure, and then hits a snag late in the game that’s almost a deal breaker. It happens.

Sometimes, you’re in trouble all the time, from the very beginning, and it feels like this movie is never actually going to be great. Then, it survives all the hurdles right up until the last minute, when it all comes together and it's a brilliant movie. I've experienced many permutations of both scenarios and everything in-between. No matter how good the studio is, how well the team is performing and how good the people are that are trying to make the movie work, there are always new things that come around that make you understand your movie better.

DS: Is part of that because as time goes on, there’s more elaborate visual development to bring the story to life?

RdC: The visuals do help you tell your story clearer. Sometimes there are opportunities to boost you so that you don’t have to use words to say what you're going to show. But it's more about how the journey of the storyteller is finally at that top level of their game.

That's what I believe happened with Inside Out. We were finally the right storytellers that had the right story to tell. We were naïve in the beginning -- we didn’t have all the data, the experience. We wanted too much. We only wanted specific things and wanted to exclude other things. We thought we had everything we needed and then actually found we had too much. Tearing it down can make the message louder and clearer.

Those kinds of things, it's hard to know until you try. When you're wandering, over a number of years, it’s like, “Why?” Well, because making the reels [story reels] and making it perform as a movie is the only way to gauge if it moves you, if it affects you. And that takes time. You have to make the movie as if you were going to release it next month… [you have to] believe in it. Then, when you get these notes [comments from colleagues], it's kind of heartbreaking… “You don’t need that much at this point,” or “You need a little more of this.” You think, “I thought it was amazing already! Why are we dumbing this down? Why are we making that longer? Why are we cutting this shorter?” At that point, you have to walk away a little bit and say, “OK, let's do it.”

Then, when you do, you live with that choice because you want the movie to be good. You start thinking that there is an entire studio that wants this movie to be great and you may be the only one that's standing in the way of that happening.

DS: No pressure there. You’re just the person keeping the film from being really good.

RdC: Yeah, you could be, because you have a very powerful vote. I have sway with Pete so if he decides to listen to me, I would be one voice that counted. If he decides to listen to other people, they would matter too. All that decision-making as a storyteller, especially in a big production, in a studio where money and time count, involves a high level of stress. And if you haven't made movies before, that would scare you into conforming too early, making choices out of convenience or doing things that are ill-advised because you feel a little too full of yourself.

DS: Is this where the phrase, “Trust the process” got its start?

RdC: You have to trust that this process is going to teach you something about “you,” right now, at this point in your life as a creator, that you probably need to hear. If you're smart enough, you pay attention.

DS: Do you have situations where some folks involved in the story process can articulate better than others, so there are ideas that take longer to evolve because whomever is championing them is just not getting their ideas across?

RdC: That happens to everybody regardless of how good they are. There are people who are really good at making movies. But on some projects, they will have a longer turn at the wheel because they are having a difficult time finding it. There are days where everybody's brilliant. Then there are days where none of us are.

DS: Where everyone's a hack…

RdC: …Where we're all frauds. That's why it's humbling. Because as much as we believe in ourselves and believe in our missions and skills, the humbling thing about making movies this way is that it shows you without any uncertainty, when you play your movie [story reels], that you're going to get “this” response. Whether you like that response or not, that is how the audience is viewing your movie. Whether you think it shouldn't be that way or not, there it is -- you can't argue it. You're probably a really good filmmaker and storyteller, but on that point, you're not seeing it and maybe you should open your eyes.

DS: Being here in Asia, coming from the Philippines, with the film business more international now than ever before…

RdC: Yes, it is. Thank goodness.

DS: While that means a lot of new opportunities for filmmakers in Asia, they don’t seem to be embracing many of the hard learned lessons from the West…

RdC: No, they don’t.

DS: From your perspective, how can you help make that happen? What’s needed to help effect change?

RdC: I wonder about it myself. I tend to do these talks everywhere I can [in Asia]. I like to evangelize because it doesn’t seem like it's a very complex secret. Because when they [filmmakers and studio execs] ask, what is the secret [at Pixar], I tell everyone, you won't like it. You're not going to like what I have to say because it doesn’t sound sexy and it doesn’t seem like a secret. When you tell them, they feel like, “Well, we'll listen to someone else. The process that Pixar has, they're like a cult, they believe in it.”

It doesn’t have to be that hard. But a lot of people are suspect, and they might be right in certain instances, but I believe in it personally. I’ve grown up in it and tested it myself, when we're really good at what we do and we are still failing.

It actually humbles you to know that if you give in to those lessons, if you do a lot of work with the right story and the right revelations that follow, you will be rewarded for your patience. It sounds mystical, but that's the only way we've made films. We’ve failed too -- we're not infallible, but our process has served us well more often than not.

There are no iron clad rules about the business. But what I wish other studios could understand is that at Pixar, there is loyalty to its storytellers, its story crews, it's designers and its cadre of people that make these movies. When you make mistakes, when you follow certain things that lead to a dead end, the philosophy of the studio, coming from Ed Catmull and John Lasseter, is let’s look at that, it didn’t work out, but let's find out how to use it as an opportunity.

They [Ed and John] actually love that part, too. Of course it hurts, it stings and it costs, but they also are wondering if there's a way to use this [mistake] to your advantage next time, that you'll learn something from this. Most places would lose their nerve because as much as a lot of people have a lot of funds, they don’t have a lot of patience because there's no core or culture there that says, “We've got to keep going, even though there's no actual results yet.”

Why would anyone listen to somebody like that? Because they haven't experienced it. They haven't made Toy Story with that process. They haven’t made Finding Nemo with that process. They haven’t made Inside Out with that process. There's no way they’d say to the rest of the company, “We've got to follow Pete Docter into the woods and we’ll emerge successful five years later.” They'll lose their nerve because they don’t have any data that says it will pan out. People will get nervous.

DS: Because so many Asian film financiers are not from the film industry and have little or no experience making films, do you think they look at animated films and figure, “How hard can it be? It’s a cartoon!”

RdC: Absolutely. Most of the time, I hear, “How hard can it be?” The argument being thrown in our faces all the time is that Hollywood buys scripts, shoots them live-action, then rewrites them on-set and makes blockbusters. But you have to look at the law of averages there. How many movies in Hollywood actually get made with that system and what is their percentage of success?

I'm not pooh-poohing it. I'm just saying that everybody in the industry faces the same odds. At Pixar, we double down on our people and process in the hope that making mistakes actually leads us to the right answers. We try not to give up on our people. That's our process. It takes a long time [to make a film] and you can lose your nerve along the way. You're right. Investors want a quick return on their investment. They also expect confidence while things are in flight that in the end, they're going to turn out well.

DS: They want low risk and fast returns.

RdC: Yes. I can't blame them. That's what you're in the stock market for if you're trying to create wealth. If you invest in movies, you have to be there for their long haul. You have to have faith in storytellers and hope that the market is ready for a great story. There are lots of great stories that never find an audience too. That happens.

DS: Asian cultural history is so rich, filled with so many wonderful characters and stories. Yet we seem to see so many films from Asia that either mimic or outright copy Western properties.

RdC: I've seen this a lot. That's why I tend to campaign when I speak and they [Asian audiences] don’t always like to hear what I have to say. I've done talks in the Philippines and heard people there say, “The market won't respond to stories about us. Audiences don’t know who we are.” I'm thinking, “Thank you. I guess you didn’t hear anything that I was saying.” The thing I see is that in Southeast Asia, and in other countries as well, what tends to be replicated is the cadence and texture of an American production because it's what they grew up watching. That’s the only product in town to look at. It's a template.

They even want the same departments in their studios that are in the credits of our films. “We need one of those, we need one of these.” They want to replicate it. They want to replicate the cadences of a movie that's come from Hollywood. Those are stories that are not their own. It doesn’t follow their own cultural narrative. My hope is that if you tell stories about your culture, that your people will recognize themselves in those stories, and they'll watch. That translates to commerce.

It's a very simple formula, though it's not easy to achieve. It's a long-term game. I want to see stories from the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka and Thailand. I want to see all of those stories. But, they have to actually invest in their own stories. And, they have to do it over a long period of time. Those audiences have not seen those stories even in their own country. They're not used to seeing their own stories on the screen. They're waiting for a major studio to take up that project. Why? A major studio would not know what their culture is all about.

Tell your own stories and investors will pay attention. I say this to every marketing head I meet. Its' a good business model. Regardless of what the culture is, there are ways to tell stories better when the subject matter comes from some authentic place.

An example is My Neighbors the Yamadas. It's an animated cartoon, done in 2D by the Ghibli Studios. When you watch Yamada stories, you can see your own family…and you're not Japanese. It's hand-drawn. It's a cartoon. But a lot of people love that movie because it reminds them of their family. Any family becomes every family in our universe of storytelling and movie making. I've been watching westerns all my life but I don’t live my life as a cowboy. I watched musicals, about people in Europe and Austria, like The Sound of Music. I never lived in Europe. I've never been Austrian. But I love The Sound of Music.

DS: If you had a magic wand, if you were going to set up a studio somewhere in Manila, or Jakarta, or Shanghai, what would you do? What path would take?

RdC: My fantasy is not a studio. My fantasy would be [setting up] a university, teaching what I believe the philosophies of Ghibli and Pixar Studios have been for the longest time. We make stories. We believe our vocation, our craft and our art is intertwined with our lives and the way that we live. You have to sustain a community of creators that would stay with you and keep making stories over a long period of time. We're not just trying to make blockbusters and movies to sell, although that has to be part of your business plan because everybody's got to eat, to pay the bills.

People stay loyal to these companies. Audiences stay loyal to Pixar and the Ghibli Studios because of what they stand for, the stories they stand for. That's an investment in a culture and a group of people who over generations, tell stories that are meaningful, rather than just engage in a business model that creates good business. It also creates students that graduate to become major players in the design of storytelling, a legacy that you can count on to keep going over the decades. A pantheon of great storytellers that would grow out of that culture of storytelling.

DS: So what’s the future for the next generation of storytellers? Few studios have the resources of Pixar and Disney. What’s the future for lower budget animated features?

RdC: I don't know -- it's a very complicated question. There's a way to be prudent and frugal about your budget but then there have to be command decisions. Eventually, time and money and resources are the things that you battle. Pixar can stay in the long game because they invest in their studio and in their people over a long time and can rely on them to stay. If you have a small studio, you don’t know if your people will stay for you. It's not just the studio's choice when it comes to talent and leadership.

But smaller productions have quite an opportunity, because since they know they can't play in the big studio game, they have a different kind of story to tell. They should own that and not see it as a limitation that they won't be able to play at a Pixar level. They can be a little more creative. It actually spurs even more creativity when you don’t have those limitations.

I love scrappy productions that want to succeed because these smaller films will embrace new ways of looking at animated features. They're already risking a lot with an investment that for them, is very big. They have a chance to win big if they do something that is not the norm. Because of the circumstances, they're being forced to step outside the usual creative box. I have a lot of faith that there's a smaller studio that will tell a story even the bigger studios are going to have to pay attention to.

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.