Jacques-Rémy Girerd discusses the making of his latest animated feature.

There's more than one cinematic Tree of Life to experience. Aside from the highly anticipated Terrence Malick opus coming May 27, there's Jacques-Rémy Girerd's second animated feature, Mia and the Migoo, currently playing at the Laemmle Sunset in LA in an English-language version featuring the voices of John DiMaggio, Whoopie Goldberg, Matthew Modine, Wallace Shawn and James Woods. In fact, Modine is producer of the English-language version along with distributor GKIDS (The Secret of Kells). Mia and the Migoo pits a young girl in a fight to save the ancient Tree of Life in a construction site, assisted by the shape-shifting forest spirits called the Migoo. Girerd, founder of the French animation studio, Folimage, talks about his creative choices and why Mia and the Migoo means so much to him.

Bill Desowitz: What are the origins and inspirations for Mia et le Migou and how did you get the financing?

Jacques-Rémy Girerd: A tree planted upside down that really exists, which I actually saw in the Republic of Benin, near Ouidah. A 300-year-old Iroko (type of tree), with roots above-ground and foliage below. This tree is an important symbol of regional peace ever since the wars of the King of Abomey in the 18th century. We were able to raise a budget around $10 million, which means that we could not waste anything.

BD: How did you conceive the story, the characters and the essence of the fable?

JRG: The tree led to the script. I created the script around that image. And also around the two main characters, Mia and the Migoo, the weak and the strong, who switch their character traits.

BD: What were the biggest design challenges in figuring out the look of the characters and the world?

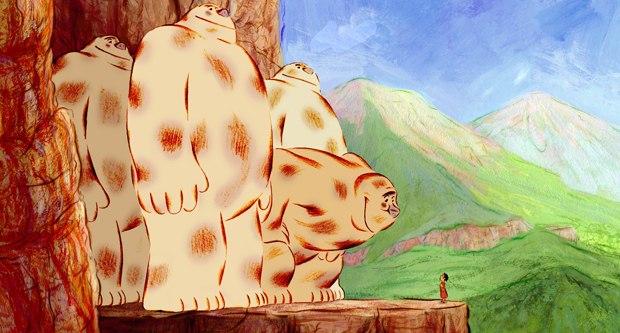

JRG: The character that was most difficult to create was the Migoo. The Migoo is not a spirit, a golem, nor a god; we had to find its form and its material. We didn't want to make it a gentle plush monster. The idea that he could be made of mineral, vegetation and animal materials guided our research.

Throughout the course of a year, we came to many different forms, none of which really worked. It wasn't easy to balance a film with tiny little Mia and a huge giant. This is how we came to the idea of changing the size of the character, so he is sometimes small and sometimes large. That resolved a lot of stuff with the mise-en-scène and what's more, we were freed from having to come up with a definitive form.

BD: Talk about the inspiration of Van Gough, Monet and Cezanne for the backgrounds and their aesthetic importance to the film.

JRG: At Folimage, we have always admired and been inspired by our French painters. The impressionists, for example, left indelible traces on our collective unconscious. In their pictorial approach, their way of managing color and light, managing contrast, questioning realist colors, purifying forms. The fragmentation of brush strokes suggests the forms and shapes. We no longer see the original model, but we can imagine it. It exists as an abstract, otherworldly vision.

More than Matisse or Van Gogh, it was actually Raoul Dufy that most inspired Benoit Chieux, the graphic designer. Raoul Dufy isn't well known in France but his work is spectacular and strong. He truly invented a style of his own. He's a little bit different from the rest of the impressionist genre. His style gave us paths for research. Benoit and his team knew how to take this and create their own style for Mia, which demanded months of work to finalize.

BD: Tell us about the animation process and its challenges and how it compares with your other work.

JRG: This film maybe could be compared to my other films - L'enfant au grelot, Ma petite planète chérie, La phophétie des grenouilles (Raining Cats and Frogs). I think that you can find a tone in common among these films, a way of animating that is very close. Regarding the illustration, each film is unique, because we like to start from zero each time -- we question everything. This method is risky and expensive, and it's also a little destabilizing for the teams at Folimage, who have to relearn everything, but it's our way of not boring ourselves, of renewing ourselves, to always be children making a film for the first time. To put ourselves in danger in order to survive.

BD: How did you coordinate the work between your studio, Folimage, and Enarmonia (Turin) and Gergtie-Colourland (Milan)?

JRG: All the creation of the film was done in France at Folimage. Enarmonia participated in animating characters by hand, and Gertie was responsible for colorizing a part of the film (digital gouache).

BD: What software did you use and did you try any new techniques?

JRG: We used Toons, After Effects, Photoshop and a bit of 3D (through 3D Studio Max) for vehicles such as helicopters and trucks. Some special effects are shop secrets!

BD: What is the significance of Mia et le Migou for you personally?

JRG: It's partly an opportunity to talk about the environment, the protection of the planet. It's a year-round job to continue to convince world to pay more attention. The nuclear catastrophe at Fukushima continues to remind us of the fragility of our Earth, and how important it is to better respect a natural equilibrium.

BD: Have you seen the English-language version?

JRG: Yes, I saw the film at its New York premiere, and also on DVD at home. The American version has a different energy. In the USA, you're more familiar with entertainment compared to France where poetry is more common. But all of that is in the margins. The U.S. version is very good.

BD: What are you currently working on?

JRG: I've been working for three years on a new feature film, Tante Hilda! (Aunt Hilda!). It's going well. With this film, we've gone headfirst into a never-used aesthetic which requires a lot of work with research and development. There is a little bit of Sempé and Brétecher in the characters and the decoration is colorful. It's a comedy, a little off-kilter and crazy, and will come out in 2013. The American public should like it. We also just released a new film in France, which was presented at the NY Int'l Children's Film Festival -- A Cat in Paris. A film noir, or "polar," as we call it in France. The next film from the directors of A Cat in Paris, Jean-Loup Felicioli and Alain Gagnol, actually takes place in New York. It's called Phantom Boy.

GKIDS will actually be distributing A Cat in Paris in the U.S., where it is currently playing the San Francisco Int'l Film Festival, Seattle Int'l Film Festival, and is featured next month at Annecy. It will be released in select U.S. theaters in the fall.

Bill Desowitz is senior editor of AWN & VFXWorld.