Debut feature from Studio Ghibli alums Hiromasa Yonebayashi and Yoshiaki Nishimura taps into the visual style and storytelling sensibility for which the legendary studio is known, hoping to pick up the mantle of creating world-class animation for all ages.

Mary and The Witch’s Flower, the debut feature from Studio Ponoc, arrives in U.S. theaters this Friday courtesy of indie animation distributor GKIDS, preceded by a one-night nationwide premiere event from Fathom Events.

The 2D anime feature is directed by Academy Award-nominee Hiromasa Yonebayashi (The Secret World of Arrietty, When Marnie Was There) and produced by Studio Ponoc founder and two-time Academy Award-nominee Yoshiaki Nishimura (The Tale of The Princess Kaguya, When Marnie Was There). Launched in 2015 with a team of veteran Studio Ghibli animators, Studio Ponoc taps into the visual style and storytelling sensibility for which the legendary studio is known, hoping to pick up the mantle of creating world-class animation for all ages.

Based on Mary Stewart’s 1971 children’s book, “The Little Broomstick,” and featuring a script by Riko Sakaguchi, Mary and The Witch’s Flower centers on an ordinary young girl named Mary, who discovers a flower that grants magical powers, but only for one night. As she is whisked into an exciting new world beyond belief, she must learn to stay true to herself:

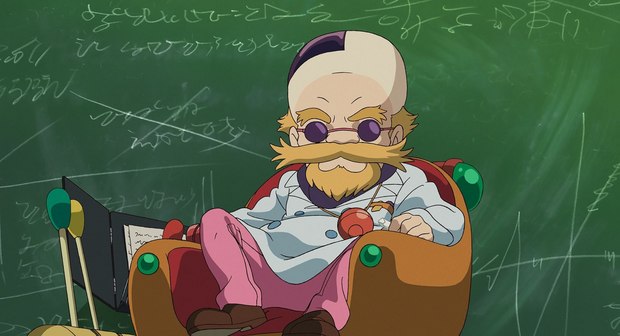

Mary is a plain, young girl, stuck in a rural British village with her Great-Aunt Charlotte and seemingly no adventures or friends in sight. But a chance encounter with a pair of mysterious cats leads Mary into the nearby forest, where she finds an old broom stuck in the overgrowth of a nearby tree, and the strange blue glow of the fly-by-night flower, a rare plant that blossoms only once every seven years. As the broom comes to life and lifts Mary high into the skies, she discovers a mysterious school for witches above the clouds. But the charming headmistress Madam Mumblechook and bumbling Doctor Dee are not all that they appear, in a twisting tale that reveals even the most ordinary-seeming children are capable of the most extraordinary adventures.

The English-language version of the film, directed by Yonebayashi and produced by Geoffrey Wexler, features the voices of Ruby Barnhill, Kate Winslet and Jim Broadbent. The English dub was recorded in London in September 2017, and had its premiere in Los Angeles at the inaugural ANIMATION IS FILM Festival in October.

AWN sat down during the festival with director Hiromasa Yonebayashi and Studio Ponoc founder Yoshiaki Nishimura to learn more about the production of Mary and The Witch’s Flower, which spanned two-and-a-half years and was completed with the help of 150 artists and a mix of OpenToonz and RETAS animation software.

For Yonebayashi, continuing the tradition of 2D animation in Japan is a vital task. “Japanese animation consists of a very wide range of works. There are works aimed at children like Pokémon and Yo-Kai Watch. And then others that are aimed at adults which have a lot of violence or eroticism in them. So, we can say that Japanese animation culture is very broad,” the director remarks with the aid of an interpreter. “But I think with the closing of the production division of Studio Ghibli there may be something that is lost. And that is films that can be enjoyed by children as well as adults. The United States makes a lot of films like that, but in Japan, it seems to be segmented into different types of animation. So, I want to continue that tradition of film, making high quality films that can be enjoyed by everybody from children to adults. And to continue the 2D animation tradition of Japan.”

While Mary and The Witch’s Flower was produced primarily for Japanese audiences, the fledgling studio already has its eye on the global film market. “We are very interested in computer animation,” says Nishimura, acknowledging that CG films command bigger budgets and have to be developed and marketed for a worldwide audience in order to be profitable. “[Right now] the budget is kind of limited,” he explains, while declining to name a figure. “We don't have a sales network to the world like Disney or Universal Pictures. Maybe someday we can have that kind of sales network, so we can create that kind of big-budget film, but right now we are creating a film for the Japanese market and after that we are selling the film to France or Korea or other territories.”

The animation in Mary and The Witch’s Flower is crisp and clean, with an almost fanatical devotion paid to the detailed scenery of the English countryside, while the fantastical world of Endor College, a school dedicated to training witches, showcases the boundless imagination of the director. “There are two worlds in the film, the fantasy world and the real world,” Yonebayashi recounts. “I think in terms of viewing the real-world scenes people will bring their own knowledge of the real world to the film. So, I thought it had to be very faithful to how the real world looks like. And even with our low budget, we did go to England to look at the locations and the houses and nature of England so that I could faithfully create that on the screen,” he says.

“But for the magic world I wanted to have a completely different look,” Yonebayashi continues. “I had different types of colors and whereas in the real world, we valued nature and its presentation at the indoor college garden, it was very artificial with strange colors. In the real world, we used natural colors, but in the magic world, we used lots of mixing of different colors to make it look like a hodgepodge and a mixture of different things.”

The titular Mary is an unstoppable ginger, filled with empathy and a depressive streak in equal parts, and sporting enviably fierce eyebrows that place her on par with any Ghibli heroine. “Mary has a complex, particularly about her red, frizzy, unruly hair that she ties up in pigtails with a ribbon. And whatever she attempts to do, things don’t go well. She’s clumsy, she’s a little too rash and hurried,” Yonebayashi relates about his approach to designing the character. “But as she goes on the adventure, she starts getting in touch with an internal strength that she has, and at some point one of the ribbons has come off and she consciously takes the other ribbon off, no longer caring about her complexes. She goes to save Peter. He shows her becoming more powerful and becoming a stronger person with a particular focus and aim in her actions. So that internal aspect I tried to show with external character design.”

But for a fantasy film centered around a magical flower and an entire college dedicated to magic, the message of Mary and The Witch’s Flower is rooted solidly in the real world. “In 2011, there was the great east Japan earthquake and tsunami, and then the nuclear power plant accident. That kind of disaster makes us doubt what we trusted before,” Yonebayashi explains. “And then after the disaster, there were many issues of trust and many rumors that flew about. And now with the Internet being so pervasive, it’s hard to tell what is truth and what is not truth. And among the things that we can’t trust is magic. So, I think this was a chance to show that we don’t need to rely on magic. We can move forward trusting ourselves and relying on ourselves in the real world.”

Yonebayashi seeks to tell a story about magic for the present day. “And in my own case, of course, I have left the magical world of Studio Ghibli and come into my own reality and have to think about moving ahead on my own without that magic,” he adds. “And that I think could be a theme for each of the viewers that view the film as well.”