Janet Hetherington examines how Marjane Satrapi's graphic novels were adapted to create an animated film that stands apart.

Persepolis is the name of the Persian capital founded in the 6th century BC by Darius I, which was later destroyed by Alexander the Great. The name carries the history of a grand civilization, besieged by waves of invaders, that carried on through millennia -- a heritage that is deeper and more complex than the present-day view of Iran may reflect.

Persepolis is also the name of the acclaimed graphic novels, published in English in 2003 and 2004, that tell the personal story of author/artist Marjane Satrapi. The books illustrate -- both figuratively and actually -- the life of a young girl in Iran during the Islamic Revolution. The story follows a precocious and outspoken nine-year-old through young adulthood, and illustrates the challenges faced by a modern young woman trying to forge an identity while having to conform within a tyrannical society.

Satrapi co-directed, with Vincent Paronnaud, the animated film version of her memoir, and she notes that animation was her first choice for the adaptation. "With live-action, it would have turned into a story of people living in a distant land who don't look like us," Satrapi says. "At best, it would have been an exotic story, and at worst, a 'third-world' story.

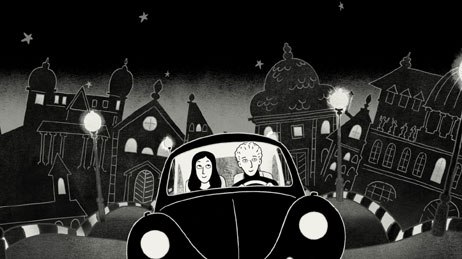

"The novels have been a worldwide success because the drawings are abstract, black-and-white. I think this helped everybody to relate to it, whether in China, Israel, Chile, or Korea; it's a universal story. Persepolis has dreamlike moments; the drawings help us to maintain cohesion and consistency, and the black-and-white also helped in this respect, as did the abstraction of the setting and location."

However, creating an animated film was not the first choice of producers Marc-Antoine Robert and Xavier Rigault (2.4.7 Films). "We were looking for the right project," Robert says. "I happened to know the new generation of French comic book artists quite well, and I'm a friend of Marjane's. I offered to write an original script for her, because I didn't want to work on an animated movie at all! At France 3 Cinéma, we'd produced a few of them, so I knew how complicated it was. Finally, we ended up having this crazy idea to adapt Persepolis, and turn it into a black-and-white animation movie!"

Standing Apart

As a French-language, 2-D, black-and-white animated film that deals with social, political and cultural issues, Persepolis already stands apart from the CG, full-color animated movies that dominate the market. And while Persepolis will see a North American theatrical release in English on December 25, it first garnered attention during a successful festival tour in 2007. The film was an official Selection for the 2007 Toronto International Film Festival, an official Selection for the 2007 Telluride Film Festival and the official closing night selection for the 2007 New York Film Festival.

Persepolis has major awards buzz, and received the Cannes Film Festival 2007 Jury Prize and the award for Best Animated Feature at the Ottawa International Animation Festival. It tied with Ratatouille for the Los Angeles Film Critics Association 2007 award for animation, and was nominated for best animated feature in the International Animated Film Society's 35th annual Annie Awards. Satrapi and co-director Paronnaud were also nominated for directing in an animated feature.

In addition, Persepolis received a nomination for a 2008 Golden Globe Award from the Hollywood Foreign Press Association -- but not as Best Animated Feature. Instead, the film is being considered in the Best Foreign Language Film category. Similarly, Persepolis is the official French selection for the 2007 Best Foreign Language Film for the Academy Awards.

The subject matter and the presentation have a lot to do with why Persepolis is being viewed as a work on its own, beyond its animation. As for translating the graphic novels into film, having "instant storyboards" in hand might suggest that the adaptation was an easy one, but this was not the case.

"We decided with Marjane and Vincent that there would have to be an adaptation of the graphic feel of the book, not simply a transposition," comments producer Robert. "Having just black-and-white hues was not possible; it would have been too much of an artistic constraint."

In the film version of Persepolis, the story is presented as a long flashback. "We had to strike the right balance between the crucial moments and the insignificant details of everyday life; it was hard to choose what had to be kept and what to leave out," says co-director Paronnaud. "After a while, we forgot about the book and worked on the script."

The approach to writing the script was unusual, to say the least. "For three months, we met every day for three to four hours," says Paronnaud. "Neither of us can type, so we used a pencil because it can be erased. We'd read what had been written, crossing out, rewriting, cutting, etc."

Defining the Design

The look of the film was equally important. "As Marjane's characters couldn't be anything but sheer black-and-white, we focused on the production design," Paronnaud says. "As we couldn't have a black or white background, we had to start from scratch. I used pictures of Tehran and Vienna as inspiration, without being totally dependent on them, and integrated various grey shades. At the same time we had to bear in mind not to soften the graphic strength of Marjane's universe. We focused on fluent lines, talked a lot with [art director and executive producer ]Marc Jousset, and finally came up with a classic design."

The animation for Persepolis is credited to the Perseprod studio and was created by two specialized studios: Je suis bien content and Pumpkin 3D. "The question of which technique to use arose very quickly when we discussed the movie," Jousset recalls. "We started with 2D images on pen tablets, but we were not totally happy with the result. The lines lacked definition. It also seemed logical that Marjane should be able to work with the animators using the tools of her trade -- paper and ink. It was clear that a traditional animation technique was perfectly suited to Marjane's and Vincent's idea of the film."

Development for Persepolis took a long time due to the sheer number of characters to address. "For Marjane's character, there were five separate steps: little girl, preteen, teenager, young woman and adult," Jousset says. "Since it was also based on real events, and took place in Tehran under the Shah's regime, then under Khomeini's revolution, (not to mention Austria), we had to take into account the way people were dressed."

Jousset continues, "There are scenes taking place at the university, in airports, at a punk concert, so it was impossible to draw only two or three characters. We had to animate a good deal of extras. However, we were lucky. Marjane drew all the characters. I thought we would have 200 model sheets to do, each character seen through different angles, so there was no discrepancy from one shot to the other, but actually we made over 600!"

The number of characters aside, the choice of black-and-white presentation offered its own challenges. "Using only black and white in an animation movie requires a great deal of discipline," Jousset says. "From a technical point of view, you can't make any mistakes. As soon as an eye isn't in the right place, or a pupil not perfectly drawn, it shows up straightaway on the large screen."

"It's even more obvious in this particular film," Jousset observes, "since it's not a cartoon with codes, conventions and distortions. We were closer to Japanese animation because of the story's realism, but we couldn't apply the techniques used in manga. As a result, we had to develop a specific style, both realistic and mature. No bluffing, no tricks, nothing overcooked. With animation director Christian Desmares, 20 animators worked on the movie."

Jousset says that co-director Satrapi had an unusual way of working. Each sequence (and there were some 1,200 shots) was given to an animator, and Satrapi insisted on being filmed playing out all the scenes. "Given that she's a genuinely talented actress, it was a great source of information for the animators, giving them an accurate approach to how they should work," comments Jousset. "It was also very encouraging for them that she was so committed and passionate. Usually, in animated movies, directors are rarely so concerned with the day-to-day work on the film. After animators, the assistant animators put the finishing touches to the drawings and check them against the original."

Jousset notes that while Satrapi's drawings look very simple and graphic, they proved difficult to work on because there were few identifying marks. Some 80,000 drawings for around 130,000 images were created. "That's quite reasonable for a feature made in the traditional way," Jousset says.

A French Feature

Producer Robert notes that Persepolis cost 6 million euros to make. "It's slightly above average for a French movie," he says, "but it's a regular budget for an animation film."

In its original French casting, Persepolis is voiced by such accomplished actors as as Chiara Mastroianni (Marjane, as a teenager and adult), Danielle Darrieux (Marjane's grandmother), Simon Abkarian (Marjane's father), Ebi Gabrielle Lopes (young Marjane), François Jerosme (Uncle Anouche) and Catherine Deneuve (Marjane's mother, Tadji).

The English version features the voices of such notable talents as Sean Penn, Gena Rowlands and Iggy Pop. Catherine Deneuve reprises her role in English, as does Chiara Mastroianni.

"Marjane's script was terrific," Deneuve says. "It was not only very true to the books, but it also included a genuinely cinematic narrative. We met at the studio, and she played and directed opposite me. She was always there for me, paying close attention. She was very specific, yet gave me a great deal of freedom playing the scenes, with no visual backup or specific schedule."

Mastroianni comments that, for her, finding the right tone and rhythm for the voice-over was a big challenge. "The scenes with dialogue weren't a problem; it was the narrating that was more difficult," she says. "It was a really different skill, and was hard with no backup. This was the part we worked on most, as soon as the footage was available, as I wanted to be able to hone my voice to match the pace of the scenes better."

Playing Satrapi also proved stressful at times. "I imagine it must have been strange for her, too," Mastroianni says. "After having written the books by herself, she suddenly finds strangers interfering with her work. I could tell that certain scenes reminded her of emotional memories, and sometimes I found that testing. Yet, I think she toned them down, both in the books and in the film."

Olivier Bernet joined the production as composer of Persepolis' original score after speaking with co-director Paronnaud, who is also a musician. "The music plays an active part in the movie," Bernet says. "It becomes part of the setting and the action. In a nightclub, one of the characters even says, 'What shitty music!', so it becomes a challenge, a sort of aesthetical exercise, and it's quite exciting for a musician."

Bernet did his research before composing the score. "When Vincent told me about the movie, I read the books again, and I stared trying things out," Bernet says. "Then, I was able to work on the animatic. Whenever a scene was ready, they would send it to me. I then adapted my work around it. It was a bit unsettling at first, but quickly became very exciting."

To address the film's four distinct parts, Bernet created four different "musical atmospheres." "The first and second ones are quite sober, and chiefly with string instruments," he explains. "The dream scenes (or the dialogues with God) are plainer: a piano, a few string instruments. I also had fun in the first half of the film when we see people dancing to disco music. It had to sound like Iranian disco music -- well, at least what I figured the music sounded like! For other scenes, I drew my inspiration from an Iranian rock CD that Marjane had lent me. The third and most diverse part is the one taking place in Vienna with the rock concerts, the hippies in the woods with their guitars, the nightclubs, etc."

Persepolis Connection

Kathleen Kennedy, longtime producer for Steven Spielberg, is credited as Persepolis' associate producer. Kennedy had sent an email to Satrapi to buy the rights to the graphic novels, but the producers told her that they had already acquired the rights and that the movie was in preproduction.

However, Kennedy maintained a connection to the project. "We sent her the script; she thought it was fantastic and told us she'd do her best to help us out, and she did," remembers producer Xavier Rigault. "She found us an American distributor, Sony Classics. They bought the movie before it was finished, which is extremely rare. She then helped us find American voices for the movie."

For all involved in the production, including Pascal Cheve of Pumpkin 3D, Persepolis was a unique experience. "For once, we had with us the person who had experienced the events, who could tell us about the characters we were drawing, and the way they would react," Cheve says. "Our work was to find a credible way to make them move. We were producing a real movie, with characters who had true feelings and who were living tragic events. The movie brims with emotions, and the whole team felt that and shared it throughout. It's probably one of the reasons why everybody was so committed."

"What I found very moving was Marjane's ability to recreate her own work in a different way," says Rigault. "It was a second personal and artistic adventure for her."

(This article features material from interviews conducted by Jean-Pierre Lavoignat in March-April 2007.)

Janet Hetherington is a freelance writer and cartoonist who shares a studio in Ottawa, Canada, with artist Ronn Sutton and a ginger cat, Heidi.