Russell Bekins travelled to the Animateka Festival in Slovenia and was schooled in the rebirth of Eastern and Central European animation.

The Animateka Festival is like a huge marketplace in a strange city. It is full of surprises around every corner, exotic goods, stories both adventurous and mundane. Like the city center of Ljubliana itself, full of students, street art, and liberty architecture with medieval overtones, it is a mix of the modern and the historical, bursting with new life and celebrating its unique Slovenian identity.

For here there is a sense of the ending of a dark age: the '90s were ruinous everywhere in eastern Europe, nowhere more than in ex-Yugoslavia, with its proud traditions of animation. One arrives with the baggage of the past: the fine traditions of the old "Eastern bloc": innovative graphics, a dark outlook on humanity, and a heightened sense of the absurd. How will this play out now that MTV has ground these very identifying factors into a very modern banality of visual overload?

Let's map it out:

Visual Poetry at the Krakow School

One of the clearest tendencies of the festival was the emergence of a uniform body of work from Polish students from Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow, under their professor, the Polish master Jerzy Kucia. "There is a singular mood in these films," noted jury member Marco de Blois of the Cinematheque Quebecois. The films coming from this school are based heavily in the graphic arts, often substituting a visual and dreamlike poetry for clear narrative. While the ambiguity of these works can often be maddening, their willingness to investigate symbols and the unconscious mind is tonic in an era where psychology is considered an offshoot of marketing.

Awarded a special mention by the jury, Joanna Rusinek's Coincidence follows a stream of consciousness from cityscapes into dreamscapes, employing motifs such as a blowing scarf, a dog, and a beggar to question whether there is some sort of strange physics that governs human encounters and gives them meaning. Another special jury mention went to Wiola Sowa's Refrains. Here, the allusion to poetry in the title tells the viewer rather directly what is up: the rhyme will come with the imagery. Cycles of life in nature and cycles of womanhood are suggested by a soft shifting cyan-green sand and mist that build the images of women interacting with nature in a monochrome pointillism.

Another entry from this school was Little Black Square, which uses the narrative trick of the chase: a boy is hunted by an all-destroying black square. Author Tomasz Siwinski uses this premise to destroy "a romantic view of the world" related to coming of age, but the fun here is to watch the sublime destruction of what seem like oil landscapes (actually they're wax) with details added in digital post. "After the fall of communism, there was nothing," Tomasz says, contemplating his job opportunities when he graduates. "Now it is a bit better. The Polish National Film Institute was established a year ago, and they have some funds."

Another entry may offer a ray of hope for Tomasz. One of the strongest entries from Poland came from working CG professional Grzegorz Jonkajtys. His vision of mankind fleeing a virus in The Ark shows a sure hand for style and a unique talent for demonstrating epic scale. He manages to finish his story with a surprise ending as well, which is something few in the festival were able to accomplish.

School's Out in the Czech Republic

There were some wonderful entries also from the Czech Republic in almost all categories: stop motion, CG and traditional animation. Michel Zabka follows the Czech traditional themes of alienation and absurdity with the premise of his stop-motion Mrs. G: a very unfriendly group of puppet pals who give the protagonist a blow-up doll for an off-colour adolescent birthday joke. Zabka follows this idea to its logical conclusion, and actually finds a touching ending despite the... well... lightweight premise. Jiri Barta's Cook, Mug, Cook develops a series of running gags in a clockwork universe in constant acceleration. Though the CG is simple, the gags are good and the ideas about the rhythm of life are even better.

Though somewhat predictable, Pavel Koutsky's Plastic People does some very funny and grotesque riffs on the mania for plastic surgery.

A pleasant example of the type of work being done by students is Klara Hakjova's Adam and Eve. Hajkova approached the classic subject by starting it all out on what seems like a two-dimensional red-and-black carpet, where silhouettes of trees move the cubistic couple around with irritating frequency. Fed up, they find a way out into eroticism, and the art itself literally bursts out into collages of feathers and colors.

Klara, who is now living in London, admits that working on the film was laborious, because she shot it with a 35mm camera, using computers to check the animation. She also credits writer Radek Fiala with helping her to find a way to move her animation ideas into an integrated story. "Now the film is finished," she smiles, as she relates her tribulations of working as a producer on her own projects in England. "In school, the teachers tell you what to do... when you are on your own you have to find your team, and find money. I'm still learning how to do it."

Baltic States: Too Cool for School

Can one still say Latvia Estonia Lithuania in the same breath?

One must be clear that Estonia, which has a grand tradition of the stop motion in Nuku Film and Tallinn Film has also come up with the stop-motion grand prize winner this year: The Dress. This is a very creepy film. It is full of insect-like fabric wrapping itself around wax-like flesh, with grey exposed organs pulsating like gills in a beached fish. While the authors are clear that they wished to say something about memory and housewives and Marie Antoinette, I personally thought twice about the bad side effects of self-assembling circuits and nanotechnology. Here is the wonderful grace of art and ambiguity: the viewer may interpret what he pleases if the filmmakers are careful to leave space to the imagination.

From Latvia came the judge's special mention, Black Box, a very complete and entertaining short about a creature that digs up a black box and finds himself the object of veneration and a global marketing campaign. Director Jurgis Krasons admits that he had help from writer Ivo Briedis in developing his concept, allowing his post-Chernobyl mutant pig-dog to inhabit a coherent world and play out a clear story line. He also revealed a secret technique to get the thousands of hand-drawn pencil sketches to keep from jittering in animation: a photocopy machine covered with sand. "It was ruined by the time we were done with it," he laughs.

More significantly, Krasons relates what inspired him to create such a unique film. "I was living in the western part of what was once the Soviet Union," he says, referring to the bleak landscape that opens his film. "Everything was like that -- broken... People saw porno films (from the West) and believed that people really lived like that." He absorbed the caustic humor that accompanied the ridiculous explanations of government machinations in the final years of the Soviet Union. There is, in fact, an English voice-over speaking in muffled tones, which seems like an error in the light of English subtitles. Not so. Krasons explains that the movies smuggled in from the West during this period were all dubbed with disguised voices so that the authorities could not trace the source.

"I like the situation in our country now," Krasons smiles. "It is like a kid. People are still stuck in the same old-fashioned Soviet thinking, but things are more positive. We are out of dark."

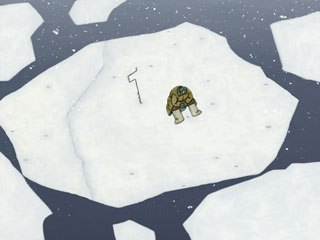

Krasons also picked up the special mention jury award for his good friend Vladimir Leschiov, whose Lost in Snow was also recognized. The film, a hymn to the utter strangeness of ice fishing and drinking, develops metaphors of isolation, perseverance, and obsession. This short is both maddening and fascinating because one sees a story line glimmering in the distance, but it is overlooked by the ice fisherman character who continues on... continuing on. Now, is that metaphorical, or what?

The Standout: Off to School

Winner of both the Audience Award and the Special Jury Prize was Hungarian Tomek Ducki, with Life Line, a vision of a strange world where "gear people" skate along sprocketed tracks. Grace comes in the form of dance moves between two of the gearheads, but darker elements soon intervene. Ducki himself, who is about to start the National Film and Television School in London, seemed surprised by all the fuss. "I developed the idea from an illustration I made," he said, gazing about in wonder at being recalled to Ljubljana for the awards ceremony. The 2D vector animation was made with a technique similar to paper-cut in which he manipulated the skeletons of the figures frame by frame.

After working out his story and some of the key moves, which included the skating duet, Tomek found his ideal piece of music, from the canon of Tijuana micro-beat maestro Murcof, and was able to choreograph the entire piece. "I started to animate it on his music because it seemed close to my idea. When I finished, I showed it to him and he liked it. He didn't ask for anything and we reached agreement with label."

Another grad student goes to London. Is this a trend?

Zagreb School and Belgrade Never Had a School, but Look at Us Now, Boy

"I have never worked in an industry," smiles Borivoj Dovnikovic Bordo, legendary animation director from the Zagreb School, who is insistent that animation is art. His 1978 Learning to Walk was featured as part of the "Made in Yugoslavia 1949-1990" retrospective. I sat down with this august gentleman and his colleague, Professor Rastko Ciric, Belgrade animator and expert in the classic canon of Yugoslav films. "I am in animation from the 1950s," Bordo sighs. "I am now 77. Now it is enough to sit, sit, sit..." Ratsko laughs. "His main business is now receiving life awards!"

"There was an abrupt stop in the 1990s," Rastko explains of the Belgrade scene. "The situation has improved since 2000, with the fall of Milosovic." He points with pride to the new generation of animators from Belgrade, including Srdja Penezik (working name D. Judd Jones) and Rista Topaloski, whose feature animation Film Noir was at Annecy this year. He also reminds us that well-known comic book artist Aleksa Gajic is working on a futuristic animated feature, Technotise Edit and I, which is due to be released in May 2008.

As for the other festival entrants, Igor Coric of Serbia offered a mordant look at what we build during our lives and what becomes of it after our death in Leftovers. This six-minute short, which begins with a bird nesting in a large bra left by a woman who has a heart attack, was one of the more complete narrative pieces of the festival.

Among the Croatian entries, Dinko Kumanovic seemed almost apologetic in presenting All Ears, a pilot for a comedy TV series, done in line drawing with computer painting. "I had no pretensions to say something," Dinko shrugged. "I just wanted to make people laugh... what I found out is that it is not so easy to be funny." He points out that there is a magic that seems to take some humorists to a higher level: "Chuck Jones' cartoons are funnier than Robert McKimson's, while Charlie Chaplin is just plain better than Buster Keaton." Dinko supports himself by doing music videos and is working on a documentary on the life of Italian piano virtuoso Michele Petrucciani. Is he too thinking of London? "I have chosen to live in Zagreb," he replies simply.

Another Zagreb entry, Transoptic, impressed with its vicious crows and symbolism of death. "It is not my intention to be dark," says creator Branko Farac, arching his eyebrows. "I wanted to create an intellectual puzzle."

Back at the table, I have one of those moments of confusion that every American dreads. I can't remember which of the two august gentlemen in front of me is from Serbia. "Forgive my ignorance..." I begin. "Why should I?" interrupts Bordo and laughs impishly. Rastko helps me out. "You know what the irony is? We are both Serbian. I am a Serb from Belgrade, and he is a Serb from Zagreb."

Home from School in Slovenia.

The final special jury mention went to Spela Cadez, who has just returned from film school in Germany with her stop-motion Lovesick. This puppet animation tells the story of a boy's visit to a doctor's office where the patients have some very unusual problems and cures. "The idea came from a dream I had about cutting out the heart and losing it in the lab," Spela explains. It's also based on her personal experiences in a doctor's office in Slovenia, where the doctors can be despotic. "I was sitting there one time, with this pain in my ear, and the doctor just kept on writing." While she admits that it would be very useful to see how the big guys at Aardman do stop motion, she is staying put. "I'm really glad to be home after five years in Germany," she says. "My direction is where I am."

Off to Where? Reflections on the Festival

This festival was a major schoolin' for at least this journalist.

It is clear that Igor Prasel achieved his ambition this year to create a large, inclusive festival that created opportunities for cross-pollination among the artists and students attending. Retrospectives of Canadian and Portugese animation, the Austrian avant garde, and the Swiss Fantoche festival left those who were hungry to see what was going on in other countries completely satisfied. A retrospective of Yugoslav historical animations and screenings of films from Phil Mulloy, Steven Woloshen and Koji Yamamura rounded out the schedule, which left this journalist with some very sore sitzfliesch.

Particularly praiseworthy is the attempt to encourage the active participation of the attendees through the workshops and working breakfasts. It might be a good idea to expand the time of the working breakfasts to allow more interaction between the filmmakers. This, after all, is their contest. If they go away without an award, they should at least be awarded an honest forum where they can expound their ideas and methods and get feedback. The Steven Woloshen workshop was particularly good at getting festival guests to sit around a table and engage each other in a manual activity. Slon, the children's special screenings and workshops, extended the festival into the community. The screenings of this remarkably well-run program were one of the highlights of the festival, and, once again, the enthusiasm of the children reminds us of why we do this work.

The composition of the jury, the selected films, and the general tenor of the work focused on the art short, not necessarily the entertainment short. While it may be beyond the purview of a festival, one may hope that somewhere these fine festival participants are meeting the people who can show them models for economic success, so that they can continue working comfortably in their medium and maturing as artists. The worrisome trend, as we have seen from the interviews with just a few of the above artists, is that many students go abroad the moment they graduate, for lack of opportunities in their home countries.

Will they come back? The mantle has been handed from one generation to the next in Eastern Europe, but only after an interval of nearly twenty years, during which all of the ground rules have changed. Both the digital revolution and the fall of communism have created the old formula: chaos equals opportunity. While it is inevitable that funding will come from the governments and that new and competent training schools will arise, it is our fervent hope that it comes in time to help this worthy generation of filmmakers. Stay tuned for developments at Animateka next year.

Russell Bekins has served time in story and project development for Creative Artists Agency and Disney. He now lives in Bologna, Italy, where he specializes in concept design for theme park, aquarium and museum installations.