Bill Desowitz has the first look at Pixar's new short, Day & Night, with director Teddy Newton.

Check out the Day & Night clip and exclusive 3-D tests at AWNtv!

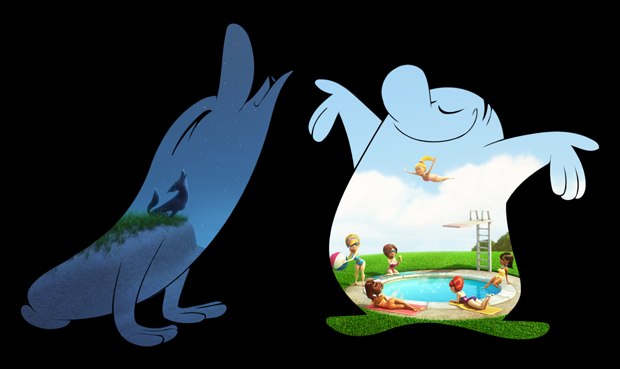

One glimpse of Day & Night, Pixar's latest short screening in front of Toy Story 3 on June 18, and you can see how Teddy Newton loves playing with shapes. His inventive six-minute tale about Day and Night discovering each other's unique qualities by offering a different window into the same world, mixes hand-drawn (the characters) and CG animation (the interior world) as you've never experienced it.

Think The Dot and the Line meets Duck Amuck (two crucial inspirations) and you'll see what I mean.

"I have a knack for seeing shapes in negative spaces," admits Newton, who attended Cal Arts with fellow Pixarians Mark Andrews and Lou Romano, and has contributed character designs to Ratatouille, Your Friend the Rat and Presto, and created the end titles to The Incredibles and Ratatouille. Newton also voices Chatter Telephone in Toy Story 3.

"One day I just put eyeballs on a keyhole and thought this would be funny as a gag," Newton continues. "I was having the eyes on the keyhole look into itself and you could see what it was seeing inside of a room. And the benefit of this was that by making it a character, the keyhole could move around the room and reveal things. This keyhole could see everything it wanted to see. I had a pile of gags that I was left with and had to make sense of that."

Yet he recalls how Brad Bird taught him a valuable lesson when they first started working together on Iron Giant. "The reason he hired me from the very beginning is that I could go on so many [visual] tangents," Newton explains. "I could just keep coming up with things that had vague [connections] to the movie but inspired him. The thing that he had taught me was how to stay on point. It took me forever to do this, and I actually got the chance to use it while making this film, because I could imagine just getting caught up in the special effects and having it end up being a big pinball machine without a point."

However, Newton was reluctant to even pitch Day & Night after so many previous rejections. "Although I could get John Lasseter to laugh, usually I had developed the material so completely that there was little room for him to participate," Newton offers. "So I didn't want to pitch anymore, but [producer] Kevin Reher kept bothering me, almost like I owed him money."

But Lasseter liked the Day & Night pitch so much that he committed before hearing Newton's other two ideas, which is rare at Pixar. "I just pitched this as a concept and we had a good back and forth," Newton adds. "He would tell me what he liked about this or that drawing, and I shaped a story around some of John's favorite things. I had one drawing of the bathing girl and the guy's stomach, and the other character got excited by it. Something about having two characters -- daytime and nighttime --together on the same horizon was a funny thing. John found it interesting but he said I should have them be more curious about what's inside. And so then I thought I should make that the whole theme of the movie: how they are opposed to it at first and then become interested through curiosity. I think that, unlike a lot of the shorts here, usually they have eight or nine different meetings with John until they get the final on their story. This one really only had three."

Plus Newton pitched the concept in 3-D, converting all of the drawings into stereoscopic walk cycles that you could view with glasses. "I always liked the way flat titles looked in 3-D for some reason. They just seem to pop out more. Actually, Knick Knack was 3-D and they showed it to me and within two minutes I got a headache. But the iris out at the end was great. I had them freeze frame that because that was our movie: It was just like looking at a punched hole.

"I thought this would be a fun way to exaggerate moments the way lighting or music can be used to enhance. We could have the 3-D play shallow in the opening and expand the depth of field as the characters look deeper within themselves. It's a metaphor as each character gets more involved in the other. One of the fun effects we were trying to achieve was creating depth between the two hand-drawn characters as well. Not just having them as the keyhole to the world, but they could walk around each other with depth."

However, as it turned out, the 3-D was just one of many technical hurdles. "The hardest part of the whole movie was the integration of CG and hand-drawn," Newton suggests. "That was nearly impossible and I really felt like slitting my wrists for two months. It was so difficult that I thought, 'Well, that's the end of my career at Pixar.' We could not figure out how to get these things together because everybody was animating blind and we didn't have the pipeline or anything to assemble these things together in a way that you could see both characters and the backgrounds simultaneously -- it was a big guessing game. The more I started storyboarding it, the more I realized why nobody had ever tried this. It's almost like a fugue in music, trying to keep two things going at the same time yet finding these breaks where each can take their turn and take some interest. And the thing that made the shots tricky is that most of them were about a minute long. That opening shot took the entire length of the production -- nine months."

Fortunately, Newton had the benefit of Sandra Karpman's expertise. She not only spearheaded stereo but also camera polish (and even rebuilt shots). And for the first time at Pixar, 3-D was not merely handled in post.

"What made Day & Night so hard was that our normal pipeline of layout, animation, lighting and rendering didn't apply," Karpman explains. "The 2D guys made a beautiful circle and the 3D guys made a beautiful block with square holes, so, for me, as a camera polisher, I had to push that beautiful circle through that beautiful block without ruining the block or the circle."

There was a further complication related to the proverbial fourth wall. "We only saw the 3-D world through those cards [Day and Night]," Karpman says, "but those cards are positioned as if they're the fourth wall, so I had to explain to the guy who was doing the CG animation that you can't break through this wall. And I had to position that wall based on the guys' feet. So I pushed that fourth wall as far as I could until their feet were actually connecting to the 3-D world."

In other words, all of this compositional positioning was a nightmare, especially with the CG animation becoming such a moving target. "And so it was a Rubik's cube," she suggests, "and it was insane and it was hard, but it was awesome because we all worked together. And I think this is one of the few times where stereo enhanced it and became part of the story."

And how does Newton think about his Day & Night? "I hope it'll have the same kind of effect as Dot and the Line and Duck Amuck: It'll stick with you for years even if you can't remember every event."

Bill Desowitz is senior editor of AWN & VFXWorld.