In Part 1 of this series, Ellen Besen sits down with maverick CG director Chris Landreth, creator of Bingo and the new, breakthrough film Ryan, to discuss the current state of CG human characters and realism.

Brad Bird. Robert Zemeckis. Chris Landreth

Hi. Im Ellen and Im here to explain a few things. Like how it is, in a year with two important CG animated features from major directors, that a short subject by a relative newcomer is going to blow all things digital out of the water. I should explain that I am as damaged as the next guy, Lord knows Ive got my own issues and that this is just my humble opinion but Im getting off topic here because this article isnt about me, its mostly about a guy named Chris

On a grey Toronto afternoon, I sat down with that splash of color named Chris Landreth to talk about three films:

Brad Birds The Incredibles, which is currently wowing audiences with its bold action sequences and wowing animators with the audacity of its all human cast;

Robert Zemeckiss The Polar Express, a less popular but still interesting mix of magic-realistic characters, exhilarating roller coaster rides, nightmarish images, Christmas schlock and a few genuine moments of real screen magic which audiences dont seem to know quite what to do with;

And most importantly, Landreths own animated documentary Ryan, which uses a hyper realistic/surrealistic approach to focus on the life and career of NFB animator Ryan Larkin.

Since each of these films tackles the challenge of creating compelling virtual humans in distinctly different ways, I was interested to see what could be discovered by discussing them with someone who is thinking about animation in truly original ways.

We started our conversation with The Incredibles.

Now while I liked this film, Im personally disappointed in its videogame structure and relative lack of character development, especially compared to what Bird achieved in Iron Giant.

Noting that, in his opinion, Iron Giant is the best Hollywood animated feature ever made, Landreth expressed his disagreement. Compared to other Pixar films Ive seen, says Landreth, The Incredibles is by far the most extensive in character development.

And he also liked how The Incredibles found, within a mainstream context, a pretty clever way to express the characters psychology. Of course, anyone who has seen Ryan knows that this is a subject close to Landreths heart.

In Ryan, the characters psychological states are revealed with physical distortions inspired by the portraiture of such artists as Francis Bacon. Reversing the natural order of things, Landreth puts his peoples insides on the outside, ending up with characters who might literally wear their hearts on their sleeve.

By comparison, in The Incredibles theres the notion of embodying the characters psychological states in their super powers. As an example, Landreth offers Elastigirl, who stretches all over the place. I look at that as being an extension of the person who, in the classic sense of the dysfunctional family, stretches herself to accommodate, rescue or enable people, says Landreth, Or the teenage daughter who has real personality development issues and what can she do? She can disappear and put a barrier around herself. What a great manifestation of these peoples dysfunctionalities.

replace_caption_besen02_VioletParr.jpg

This is an important point and one that can add a great deal of animated value to a film but, in this case, I find its just another underdeveloped potential that adds to the feeling that The Incredibles could and should have been more at every level.

Now we turned to the key area of performance where, of course, I wanted to hear Landreths opinion about CG character animation, realism and classical technique.

The standard wisdom in commercial and educational circles, these days, is that the strongest foundation for creating believable characters in CG is still the 12 principles of 2D classical animation. These groundbreaking fundamentals, which include such concepts as stretch and squash, anticipation and the use of arcs, were developed by Disney animators in the 1930s to give their drawn animated characters more life. But is this really the best and only approach for CG?

Landreth, who came into animation through a side door instead of through the usual animation schools and studio apprenticeships, certainly challenges this idea and has been adamant about exploring other paths ones that dont follow the old rules to the letter. Up for re-examination are the use of gesture and exaggeration and the whole pose-to-pose approach.

Take, for example, the idea of ambiguity. Landreth explains that 2D classical technique is based on clarity of gesture and emotion from one pose to the next. So if a character is supposed to be sad, the face and body posture should convey a united front of sadness. But though emotionally clear, the end result of this approach is stagy and the lack of ambiguity actually gets in the way of creating realistic, original CG performance.

Are the principles the only problem here or do technical limitations also get in the way of creating subtle performance with CG characters?

Look at a film like Final Fantasy, Landreth says, The problem there is not a lack of controls, in, say, the face. Ive seen the rigs for a lot of these characters and they are immensely complex. Its a relatively straightforward thing to add tons of controls, which can make anything happen to the face. If anything, a 3D animator has way more controls than he needs, rather than not enough.

Where the 2D mentality sets in, then, is in how the animator chooses to use those controls and how he/she approaches them technically. For example, a lot of the animators on Ryan liked using dope sheets because they make it very easy to break down the individual motions in a character. But that is part of the posy approach, which Landreth was trying to get away from.

Ultimately, Landreth succeeded in weaning his animators off the dope sheets. Instead he encouraged them to use the graph editor a more left-brain way to look at the animation and from that to gain a better understanding of waveform. People dont move in curves, says Landreth, Their nerves impulsively fire off a muscle contraction and that means that motions begin with an abrupt twitch and then trail off. The pattern looks like a shark fin instead of a smooth arc. And then, because there is also muscle, there is momentum, follow through, mass etc. to be accounted for.

He also encouraged his animators into giving individual characteristics to different parts of the body. And into working with straight ahead animation, rather than laying out timed poses and then defining where the inbetweens are, which tends to create a very cartoony acting style one gesture per accent of dialogue, no ambiguity allowed.

The results of these changes were spectacular, exceeding even Landreths own expectations. But the roots of this success go back a few years, to the late `90s when Landreth immersed himself in a study of the human body: how it was structured, how it moved, how it expressed emotion. The key to this was the detail that Landreth went into. Interestingly, this was exactly the kind of detail that classical animators learned to leave out in order to make actions and emotions read more clearly in 2D.

So Landreth studied finger movements and noticed the shark fin patterns they created. And he studied the performances of great film actors to understand the role that tiny facial muscles play in expressing the subtleties of emotion. Ill never forget the time he came out to a class I was teaching at Sheridan, in the midst of this study and had us all staring intently at Dustin Hoffmans chin, watching how an almost invisible muscle would begin to pull downward as Hoffmans tension increased.

Chris Landreth observed small details of movement to help him bring his CG humans to life realistically.

And he studied the important role that ambiguity plays in making performances feel real. I show a scene from Citizen Kane, says Landreth, Where Orson Welles, as Kane, is trashing his ex wifes bedroom throwing around suitcases and books knocking things over. Then I stop the film and defy the audience at any point to find a recognizable pose. In fact, the overlapping action is so complete that you cant even think in terms of poses.

Then there is the surprising range of facial expressions throughout this scene. Though Welles is clearly in a violent rage, his face is not necessarily showing anger. Instead, at one point we see concentration, at another befuddlement and at another serenity. Taken as a whole it looks like a natural acting job, says Landreth, But taken in parts its bizarre. He picks up something and his face is full of calmness and thats a quarter of a second before he hurls the object across the room.

So what does that tell you about real anticipation versus the cartoon convention?

What that tells you is that the face can be at complete cross purposes to what the action is conveying, says Landreth, The anticipation may be so far in advance of thinking and doing that there is no unified front at any one time. So you have to overlap action not only in the poses but in different parts of the body in order to realistically convey what a characters psychological state is throughout a sequence of action.

Not only does this make performance more real, it also makes characters more interesting. Why? Because it reveals internal conflict. And not just grand dramatic conflict either. It can also be very mundane, explains Landreth, And moment to moment in a way that has nothing to do with drama.

Or, I would say, has everything to do with submerged drama, which is not necessarily going to be fully revealed but helps drive the action anyway. One way or the other, this takes us to another key point, which is a rethinking of moving holds.

Most of Ryan would qualify as a moving hold, says Landreth, Its two people not really doing much and animators will tell you thats hard to do. Its easier to make Spider-Man do backflips than to do two guys sitting around and make it engaging.

At the heart of Ryan comes a moment which takes the challenge of the moving hold to its extreme. This is when Landreth says that hed like to see Larkin beat alcohol and for 20 long seconds Larkin doesnt do anything. He just sits there, downcasts his eyes, sniffs, twitches his shoulders, gives his head a little jerk and then barks out, WHAT?!

What Landreth has given us here is an advanced thinking moment not just a pause, not just a shift of expression representing a thinking moment but a detailed depiction of the brain beginning to fire parts off parts of the body before releasing emotion. Its a feat, Landreth feels, which would be very difficult for a 2D animator to pull off without wanting (or maybe needing) to fill in that 20 seconds with something.

Portraying Larkin accurately, even in such subtle moments, meant accommodating his unique way of gesturing. Breaking away from the one gesture per accent standard is a hallmark of Landreths approach. And that demands a higher level of observation and innovation to come up with an appropriate strategy for each character.

In Larkins case, his gestures are all over the place, often preceding his words or lagging after them, underscoring the idea that you cant pose this stuff. But unlike the classical approach, Landreths team did not exaggerate this key characteristic. Rather, Landreth says, We tried to capture it.

Capture it they did. In fact, they captured a whole person and all by animating from scratch. This, of course, brings the technical approach of The Polar Express to mind.

The performances in Polar Express were also captured but digitally, with an advanced version of motion capture called performance capture, which is capable of picking up even subtle movement. The captured work was then rendered digitally to give the whole film the luminous feeling of a moving oil painting. So how, then, does Polar Expresss style of capturing compare to the results in Ryan?

The side-by-side view of Tom Hanks and his CG likeness gives an idea of the detail of movement that motion capture can obtain.

Landreth had seen a making of presentation of Polar Express, which featured Tom Hanks acting with his white spots on and a split screen showing the digital performance that came out of Hanks work, Toms acting looks okay. Hes emoting, hes being physical actually showing what could be, in a two-minute sequence, kind of brilliant physical acting.

Well, that knocked my socks off because thats sure not what I saw on the big screen. So where did that performance go?

The mocap approach sort of works for the adult characters, where it becomes a caricature of the deadpan adult with a heart of gold. But the children come across not so much as deadpan, as just plain dead: soul deprived zombies sleepwalking through their parts. Unfortunately, rather than luminous Christmas revelers, I kept thinking about that banjo playing kid in Deliverance

It probably didnt help matters that the foundation performance for the hero boy was acted out by Hanks rather an actual child. But even disregarding that, the Polar Express experience only seems to prove that motion capture has the same pitfalls as its ancestor, the rotoscope.

In other words, this is another case of it doesnt matter how much detail or control you have, what matters is knowing what to do with it. While such devices can be an aid to graphic based filmmaking, they still dont fully replace the interpretive role of the animator.

So why did I ask all those questions and what do I think has been accomplished in these three films?

Well, first, in spite of Landreths enthusiasm

And though I found The Incredibles to be a romp with lots of fun sight gags, inventive gadgets and cute family interaction

And though I agree that the human characters are more successful than previous Pixar attempts

Something still bugs me about this film. Part of it is that underneath their superpowers, The Incredibles are really just another sitcom family from central casting and that makes the story rather formulaic. But even more is the fact that, while Brad Bird is clearly a great director, the hard truth about The Incredibles is that the character animation would have been far better and more believable in 2D.

In spite of all expectations, the characters come off as nothing more than puppets sophisticated puppets, yes, but puppets nonetheless. There is a mechanical quality to the movement: a feeling of marble eyeballs rolling under rubbery hoods eyelids, mouths that look like they were cut out of felt and, like creepy old Victorian dolls, REAL HUMAN HAIR! Rather than looking like real creatures that truly inhabit their own world, these characters looked manufactured and that distracts from the performance and undermines credibility.

This is not to make the bald statement that the Pixar approach is wrong just that it is limited in what it can do.

As for The Polar Express Well, think back to the beginning of this article and remember the part about finding interesting, animated ways to express the characters inner life. Perhaps, then, it becomes clear that live-action performance plus oil painting texture, no matter how luminous, does not an animated film make. You need both the fantasy concept and you need the means to truly convey it. In other words, you cant fudge this stuff.

So in the end, I have to say that, as animators, we have some important thinking to do about how we animate in the 21st century. For the moment, mocap doesnt look like its going to be putting animators out of business but that doesnt mean we can relax. We have to choose our path. From here it looks like either we continue on what will likely be the dead-end of classical animation or we can join Chris Landreth and do some trail blazing of our own.

The current 2D rules into 3D animation approach has its strengths but the reality is that the tools are more subtle now. For a long time all that could be achieved was broad acting. We were used to using bludgeons and now were being handed the finest scalpels is it surprising that we need some redirection to get the best out of them?

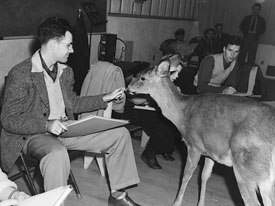

The late Frank Thomas, who was a progressive thinker when it came to the expansion of 3D CG, here, observes a deer to gain knowledge on the subtle details of the animals movements.

The pioneer Disney animators came up with classical principles by doing their homework: they observed reality and then figured out a template to guide the translation of movement and emotion into 2D. The outcome was an extension of animations possibilities from shorts through to commercial features.

But applying that template directly to CG creates a distortion factor that comes between the medium and its relationship with reality. Landreth has done his homework, too, and the approach, which comes out of it effectively, removes that intervening layer and reconsiders realism strictly on CGs terms. The end result is nothing less than the most realistic and compelling CG performance achieved to date.

What difference does all this make? Opening up animation to an even greater range of emotional possibilities is like moving from the 12-color crayon box to the 64. With greater emotional range comes a greater range of storytelling possibilities. Just as classical technique took animation into features, this transition can move animation beyond the broad strokes of the musical and family film category into the wider world of film, in a sustainable way, without simply imitating live action, on its own terms.

I think Disney himself would have approved.

Ellen Besen studied animation at Sheridan in the early 1970s. Since then she has directed award-winning films both independently and for the NFB, worked as a film programmer and journalist, taught storytelling and animation filmmaking at Sheridan and given story workshops at many institutions and festivals, including the Ottawa International Animation Festival. She is the director of The Zachary Schwartz Institute for Animation Filmmaking, an online school that specializes in storytelling and writing for animation.