The two first time directors sound off on the rigors and joys of bringing a big time animated sequel to the screen.

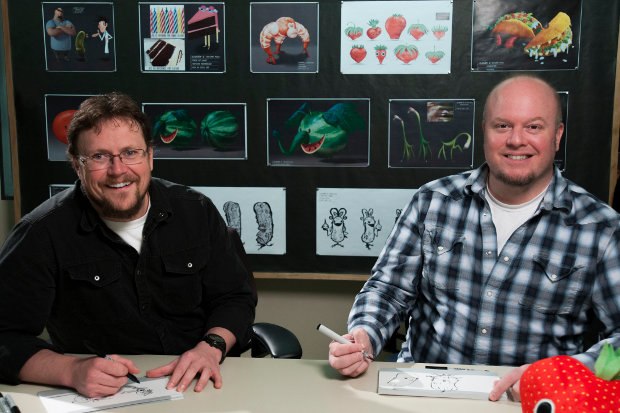

Spend a few minutes with directors Kris Pearn and Cody Cameron and you can tell they work well as a team. They answer questions for each other. They riff spontaneously on every subject, finishing each other’s sentences, expanding, expounding and rambling on about any number of unrelated topics. They’re like two kids stumbling over each other as they hurriedly explain how cool it was frying ants with a magnifying glass.

Three years in the making, their new film, Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 is the much anticipated sequel to Sony Pictures Animation’s 2009 hit, Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. Picking up the story exactly one minute after where the first film left off, Cloudy 2 tells a tale of hybrid food monsters bent on mischief and causing trouble. I had the chance to meet both directors last week at the Ottawa Animation Festival, where we talked about their first big time directorial gig, the dynamics of co-directing such a large production, the challenges of directing and being directed and how each little setback ultimately helped them make a better film.

Dan Sarto: So tell me a little bit about the film.

Kris Pearn: If you remember, the first film is about a backyard inventor, Flint Lockwood, who created a machine that could turn water into food. Everything was great for Flint until suddenly the machine went crazy and he had to use another invention, Spray-On Shoes, to blow it up. So our movie literally begins 60 seconds after that happens and he is celebrating his victory over the FLDSMDFR with all his friends and family. They’re planning their future when all of a sudden a helicopter drops from the sky and we meet one of Flint’s heroes, one of the greatest inventors of all time, a fellow named Chester V, who is a bit of Steve Jobs meets Mark Cuban with a little Richard Attenborough…

Cody Cameron: A bit of Walt Disney…

KP: And a little bit of Carl Sagan. Chester is there representing his company Live Corp as they clean up the island. The only catch is that everybody has to leave. Flint suddenly finds himself working for Chester in beautiful downtown San Franjose, California. As opposed to being the only guy with the lab coat, suddenly Flint is in a sea of lab coats and he is having a great time.

All of a sudden one day his past shows up and knocks on the door. It turns out that something weird has been happening on the island. He sees evidence of a giant cheeseburger that is eating people. Of course he figures, “Oh, my machine must still be on!” So he gets the band back together, the ragtag group of misfits from the first film and they go on this crazy quest through a food jungle, braving all these food creatures, to find and destroy the FLDSMDFR. So it’s kind of a return home.

DS: As a sequel, you’re starting with an existing set of characters and storylines. Describe the process of picking it up from there. How do you begin creating a new story?

CC: Well at the end of the first film, originally we had sequences where the food was raining on the island and starting to run around like food zombies. We even had Flint facing off against a giant donut eyeball inside this food monster…

KP: …Kind of a food kraken in the water.

CC: When we were asked to come back and do the next film we really wanted to do a lot of stuff we didn’t get to do on the first film. So…

KP: Yeah. So I guess the genesis of Cloudy 2 goes all the way back to the first film, where we were hanging on to the book and we had the genre idea of doing a disaster movie. But the whole time we were throwing spaghetti on the wall and a lot of that spaghetti fell off. Even the idea of Flint graduating, that came from the first film…which didn’t make it into the final cut.

CC: Yeah, because there was a character named Vance LaFleur that was from the Science League and…

KP: He was voiced by George Takei.

CC: So we kind of used all these leftovers we had from the first film and brought them into the second one.

KP: But that only gave us our kick off point. To answer your question, where did we begin, we all got into a room and it was like, “Okay, so we finished the first film and that was a disaster movie. Let’s do that monster movie we wanted to try.” That's sort of where we started. But, the monster movie fell away fairly quickly and turned into a noble savage story. Once we…

CC: …Once we started seeing these characters we didn’t want them to all be bad. We wanted to care about and have some empathy for the food. We started to fall in love with the food creatures. We felt that, “Hey maybe there is something good about these creatures.”

KP: Plus, for Flint’s journey, we can relate to a character who is trying to be himself within the “system.” Look at Teen Wolf or Can’t Buy Me Love, what it was like going to high school and suddenly, you’re cool. How do you keep your friends? But there is also that element of what everybody is going through. Like when you’re working in the animation industry. How do you stay true to yourself when you start to serve the machine? Those kind of themes were at play. Flint was on a quest to kind of destroy himself and so ultimately, the food is what he is trying to destroy. As Cody said, we wanted to empathize with the food. We sat in a room for about a year and just talked. There were a lot of conversations. We did a lot of boarding. We would go straight to drawings, because that’s how we liked to solve problems. Every director is a little different. Some work with a script. We like to work with…

CC: …Well we both were board artists and he was head of story on the first film…

KP: …And we had a great team. Going back to the first film, Chris Miller and Phil Lord, the directors, they ran the story department like a writer’s workshop. There were rules. You always had to be respectful. If you didn’t like an idea you weren’t supposed to knock it down. You were supposed to try to build on it or find another idea.

CC: Yeah.

KP: It was all about being constructive in support of the story. So we ran our team the same way. We got a really good bunch of folks. I think that’s where a lot of our comedy comes from. It’s those jokes that you just – you get to after talking for a while and then you get to that giggle space where suddenly the stupid ideas start to come out and those are the best ones.

CC: Those are the best, yeah.

DS: Working on a sequel, it’s both a blessing and a curse. You’re building on existing characters with a fan base. But with that fan base come expectations. How did those expectations impact your story and the choices you made on this film?

CC: Well we wanted to stay true to the characters and true to the tone of the first film. But we also wanted to take the audience to a new place. So it was about growing these characters without completely changing them.

KP: I hadn’t worked on too many sequels, so I was nervous about the expectations. But the reality is once you start making the movie, it’s the same as any other film. You’re always worried about what the audience is going to think and you’re always trying to make it as funny and entertaining as possible.

CC: We made a movie that we would want to see. We were making a story that we would want to be a part of…

KP: …and I think having made quite a few of these movies, both of us had a lot of faith that the iterative process was going to work.

DS: You trusted you’d end up with something good.

CC: Yeah, hopefully.

KP: When I’m looking at the picture as a whole, if I boil it down, it’s a little bit like when you launch a sequence and the first thing you have to do is take away the fear of that blank page, right? You know what I mean? You finally put something down on paper and then you can get going. If you stare at the paper too long, you will psyche yourself out and get freaked out. And I think it’s the same thing with any movie. When you start cracking it creatively, you literally just have to start walking into punches until you get used to it…

CC: You want to get that flow going.

DS: Speaking of expectations, your audience is a 7-year old, a 12-year old and their parents or grandparents. Or all of them. Do you think audiences judge animated films differently than live action films?

KP: Well the hard reality, and this isn’t a cynical thing to say, is that we’re trying to hit the widest possible audience. We’re sitting on a fairly large budget movie. It’s not like live action, where you can get away with making a $10 million film or a $10,000 film, where you can get away with a genre pic that sort of has a niche angle. Now admittedly, I want to communicate to as many kids as possible. That’s why we’re doing this.

So our dance is trying to find original comedy, trying to push the envelope as much as we can. But we’re also trying not to offend people because that’s not our job. Our job is to tell a story that people like. Hopefully the themes resonate and there is enough stuff in the movie beyond the jokes that is chewy, that the characters mean something people care about.

DS: So what’s the deal with all these co-directors on animated films? How do you guys divide the duties?

KP: We divide things less departmental and more sequential.

CC: We definitely had sequences that we would each…

KP: Shepherd…

CC: …or focus on. But with every scene, we each would look at everything. All the animation, all the designs. We were in every meeting. It wasn’t really until the end of the process where time was getting crunched, where we would have to split up and one would go to anim, one would go to vis dev. But the next day we might flip flop so that we could each see all of the pieces and keep abreast of what was going on.

KP: Our collaboration really extended from the story room. Both Cody and I had been working on projects at Sony for what, nine years?

CC: Yeah, nine and half…

KP: So we have spent a long time working together on different projects. For me, what I like about having somebody to talk to is that the conversation gets the ideas out of your head. It’s that action – reaction, that lubrication, that discussion…

CC: And even though in some sequences, one of us might focus on one scene over the other, we would still pass ideas back and forth…

KP: It’s the debate that was really good. Then we brought that debate to all of our departments and sort of set a tone that if anyone on the team had ideas, they could collaborate with us. It’s like…

CC: No bad ideas. There are no bad opinions. Bring everything on.

KP: We wouldn’t say yes to everything, but we definitely wanted the team to have an opportunity to help us make the movie better.

CC: Either it solidifies what’s working or shows you the flaws.

DS: This is your first time helming a mainstream big budget animated studio film. That’s not an easy gig to get. What in your backgrounds do you think made you the choice to direct this film?

CC: Well, being in the story department, you’re doing camera, you’re doing acting, you’re figuring out writing, you’re kind of handling a lot of aspects, so…

KP: You’re also pitching a lot. When you’re in the room with the executives…the politics, it becomes about you getting notes and how you respond to notes, to see how you work in that arena.

CC: Right.

KP: For executives, they’re, of course, trying to manage their expectations and fear on a project because there is a lot of money on the table. That collaboration needs to be fairly transparent.

CC: Chris and Phil, they picked us to direct the second film, but also I think the executives were already leaning towards that anyway. So it just happened to workout.

DS: Tell me a little bit about what’s been most challenging, interesting and enjoyable about making this film?

KP: For me, the most challenging part of directing is sort of the old story standby, trying to get through the screenings and learn what you need to learn and stay optimistic as you’re learning. It’s sometimes discouraging when you have those setbacks. You just have to dust yourself off, pick yourself up and try to grow from it, realizing each setback is an opportunity to make the movie better.

Even when you’re getting notes that you don’t necessarily agree with, sometimes you’re doing A, the note says do B, you have to find a third, fourth or fifth solution. Quite often, with those other solutions, you end up with a better movie. You’re forced into these compromises that turn out to be better for the movie. It’s a wonderful process. You can’t initiate it. It just happens.

CC: Adding to that, obviously we’re dealing with a lot of creative people who have feelings and emotions. It’s tough on everyone when you have to cut out a scene that someone has been working hard on. Coming from boarding, we've had to throw out hundreds of drawings. How do you work with other artists to help them work through that process?

KP: Yeah. I mean, we kill lots of our own babies. We also kill a lot of other people’s babies...

CC: So that’s a big part of our job. The fact that we have experienced this process as artists, it helps us as directors working with other artists.

KP: One of the things I was surprised about is how much I enjoyed watching other people do their job. Having been an animator when I started in this business, I hadn’t worked in that department in a very long time. I’ve been doing story. So it’s been really awesome to meet and work with that team, to see how creative and funny and smart they could be. How quickly they would get to something that was awesome. Like how close the horseshoe would get to the pin the first time we’d see a scene. How many times they made us laugh. It’s great to be an audience for your own product. Even though it’s the lines that we’ve written, the storyboards we’ve drawn, the camera we chose, they’d still surprise us. That has been fantastic…

CC: We were always being entertained.

DS: Something I ask every director I get an opportunity to talk to...

CC: Briefs or boxers.

KP: Neither!

DS: In every film there comes a day where you say to yourself, “My hair is on fire! This film is just not working.” What day was that for you?

CC: Every day.

DS: And conversely was there a point where either something happened or came together in a way where you said, “Okay, there’s still a lot to do, but…”

KP: Everything is going to be fine.

DS: Yeah. We’re going to be okay.

CC: Well, we came up with solutions to problems pretty quickly. If it wasn’t the day of, then usually the next morning we’d come in with a solution. There was a lot of pressure every single day and so it was just a matter of keeping everything together and not going crazy or losing it.

KP: I do remember one moment towards the end when we were doing Chester's story, trying to lay that in. We had no time and we’re trying to put it down and I got a phone call from Phil and I was kind of venting on him and he said, “This is why we train.” He kept his cool. This is sports that we’re doing, okay!

Actually I remember on Cloudy 1, I was head of story and we were kind of going through political changes at the studio. Everybody was kind of antsy because everybody knew something was going on. I went into Yair’s [Landau] office, who was running the animation division and basically laid it on table, “This is blah, blah, blah, blah, blah.” He patted me on the back and said, “Kris, when it rains, you put on a coat.” That went straight into the movie. So, sometimes in those moments of crisis, you get great writing opportunities.

DS: What in your backgrounds do you think best prepared you for the role of directing this movie?

KP: Being creatively flexible is a skill that you learn over the years doing storyboards. You have to rebound very quickly when you get kicked in the face. The scene is not working. You get a note that kind of throws the whole scene out and you just have to have faith that there is always going to be a better idea. You have to keep punching. As an animator I don’t know if I learned that skill as intimately, because your box is a little bit more defined. You get your assignment and it’s just the nature of production. You don’t have as much blue sky when you get to the animation side. The blue sky is scary. Story teaches you that you have to cope with constant changes, which is a skill that I know I used a lot when we were dodging the slings and arrows of this movie…

But coming from any department, if you have a vision and you’re able to stay true to that vision, but still be flexible on how you get there, that’s the trick of the job. You’ve got to bend like the reed, you know what I mean…?

DS: You’re directing everyone on the production team, but who is directing you?

CC: Well, we have executives…

KP: We have our masters and…

CC: We get all of our notes from the top.

KP: Maybe the ethereal answer is…story. The movie is directing us, and we’re all serving the story.

DS: You talk about the pressure. This is a big budget film…

KP: As soon as you put the word million in front of your movie, then add an “s” to the million…

DS: The people that are signing those checks are putting their trust in you to make a successful film. When do you stand your ground? When does someone give you the gentle elbow and say, “We really need to talk about this.” At the end of the day, how much of what goes into the film is still your decision?

KP: Wow that’s a good question. It certainly happens when you get those moments where you get a note you’re not going to embrace willingly. Our producer was always good at being blunt about that kind of stuff. However, politically what you have to do is take the note and try to figure out how to solve it in your own way. Buy the time to give you the creative opportunity to find the solution to the note. Dealing with humans, you always have to be careful about what you say and do and in terms of keeping it your movie. I think it’s in that creative basket of, “How do you respond?” I can’t choose what the weather is going to be outside, but I can choose what I wear.

DS: That’s a good answer.

KP: If you turn the microphone off, we’ll tell you a different story. If you put some beer in us, well…

DS: Don’t tempt me. Looking back now that the movie is done, is this the film that you set out to make?

CC: Yes it is. We always knew that Flint was going back to the island, something was going to happen on the island, the whole deal with the machine and the mentor that is the villain, all those elements were all there. We had an earlier version where it was Tim that first went back to the island and Flint had to go back and find his dad. But we changed that to having Chester discover something on the island and that motivates Flint to go back. There are different little plot points that have changed, but essentially the structure was always there.

KP: Yeah, it’s still a sweater. You may unravel it, but you’re not making a rug, you’re making a sweater. You might change the color of the arm and you might…

CC: You might turn a snowman into a reindeer, but…

KP: You may have another arm sticking out the back and…

CC: It might be green instead of brown, but…

KP: But then you get notes, “Why do you have three arms?”, so you take one of the arms off…

CC: “Well I thought three arms would be funny, though it’s not very practical…”

DS: Any technological innovations that came out of this production? Any new systems that were developed that helped with the visuals?

CC: Yeah. There was something that the guys call “Depth Styling.” They designed a system where as the camera gets closer to an object, it pops out into three dimensional space. As the camera moves away it flattens back out into the background matte painting. It takes less time to render stuff that’s flat rather than being three dimensional. It also helped with our look. We wanted the backgrounds to look like paintings…

KP: That was one of the challenges our production designer and art director put forth to the Imageworks team. What would be really, really great is if you can make our world look like a painting with brush strokes. We treated the jungle like Flint’s lab in the first film. It’s like a mood ring. It’s never green. The color is driven by what’s happening in the sequence. Dave Bleich, our art director would paint all kinds of textures with water color and canvas to create different feelings…

CC: Then scan them in.

KP: Scan them in and then the Imageworks team could take a leaf that was close to camera that looked 3D real and as the camera moved away it started to become textured as it fell into the background.

CC: They put that brushstroke as a texture on the three dimensional object.

KP: Totally geeked us out. The other thing is we came up with a new crowd system [Imageworks’ CRAM – Crowd Asset Management]. This is a big issue for 3D movies compared to the 2D days where you could just draw as many characters as you could draw. One of the things I think is challenging with a 3D budget is how can you make your crowds not look the same…

CC: Yeah, where every fifth person looks the same…

KP: So when you see Cloudy 2, at the beginning of the movie we have our old crowd system. Which was a fine crowd system. But if you freeze a frame you can see four Joe Towns…

CC: Not only faces, but a lot of the same outfits. It’s like there are four guys in black shirts, there are two guys in…

KP: But when we get to the island they came up with a system where they did five generic males and five generic females and then morphed them into thousands of characters…

CC: It seemed like it had some kind of randomizer where they could just pop a bunch of them out and then go through and look for the really weird ones. Like maybe there was a portly person with a pencil neck. They’d delete that one character. But the system created different hairstyles and different skin tones…

KP: We stared at the movie a thousand times. I would be watching the crowd scenes and somebody in the corner would get me laughing.

DS: One last question. In the animation business, everyone, for the most part, toils in obscurity. It takes a different type of person to work this ridiculously hard…

KP: Being ugly helps. I don’t have a choice.

CC: You have to love the art form. I grew up loving animation. My grandfather was an animator [Bob Youngquist, a Disney animator from 1935 to 1970] and I love the art form. I love the medium and I wouldn’t do it unless I loved it. You can make more money and work a lot less hours on a live action film than you can an animated film.

DS: So what part of this process gives you the most personal sense of satisfaction?

KP: I know it sounds cheesy, but when you screen the movie and somebody laughs at a joke you put in, that emotional response is so exciting.

CC: Getting the film out there, having the public laugh at stuff, going back and remembering how that joke evolved and got there. It’s really about wanting to entertain and move people.

KP: It’s not about just doing this for validation. But validation is nice. It’s nice to know that the audience has responded to something you put out there. I always get a little bump when I meet somebody who says, “I love that movie.”

--

Dan Sarto is editor-in-chief and publisher of Animation World Network

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.