John Cawley looks into the business of expanding a franchise in the world of direct-to-video.

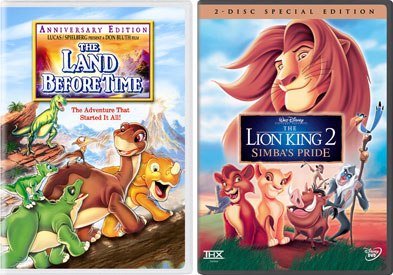

Straight-to-video franchises are cash cows and well-known properties including Land Before Time and The Lion King are among the strongest sellers.

In what some would say is the killing of the goose that laid the golden egg, direct-to-video sequels are the fodder for many a critic. Dubbed "cheapquels" by some, the trend to create more stories from hit (or even moderately successful) animated films continues to grow at an amazing rate. Starting with two in 1994, by 2005, the market was averaging around half a dozen a year. And this doesn't count the direct- to-video originals and their subsequent sequels.

What has helped fuel the direct-to-video market in animation are some of the same factors that spurred movie sequels. An existing awareness of the property makes video sales easier. In theory it is more cost effective to make a sequel, since a lot of the design work is done. And, equally important, the studio saves the costs of putting it in theaters. One often hears that a movie must make 1.5 to 2 times its cost at the box-office to break even. That is because it can cost millions of dollars to make prints, buy advertising and share with the theaters. When a home video production is done, studios just need to dupe it, box it and ship it. And if the production is based on a previous film, very little advertising is needed. A video that shouts "all new" or "2" promises a new movie to rent or buy.

Around 2000, most animated feature film budgets included the numbers for a sequel as part of the profit plan. If the feature costs $100 million to make, and a sequel costs $5 million, the studio gets two home video titles for around $50 million each. In 2003, a retail trade magazine declared, "Straight-to-video franchises are cash cows for drug stores." The article explained how sales of well-known properties, including Land Before Time, Lion King and Mary-Kate & Ashley titles were the strongest sellers. DreamWorks declared, in 2004, that it would begin focusing on franchise films. A recent editorial in Home Media Magazine stated many studios were rushing to make direct- to-video product, and that it was meant for more than just video. These studios hoped to sell the productions to TV (foreign and domestic) and even utilize it on the Web and other venues.

As mentioned, direct- to-video sequels are descendants of their theatrical brother's movie series from Hollywood's golden age. When tinsel town moguls discovered a popular character, it only made sense to exploit it via repeat appearances. (The producer of Gone with the Wind requested several times for the book's author to write a sequel that could be filmed.) After all, by using the same cast and much of the same sets from film to film, a studio could economically create additional adventures. Also, with a known character, less money and time were needed for advertising. From Andy Hardy to Blondie to Charlie Chan to Francis the Talking Mule to Ma & Pa Kettle to Tarzan, sequels were the lifeblood (and sometimes savior) of the movie industry.

In the early '80s, The Japanese released "OVAs," which consisted of three types -- productions based on manga; productions that were too "racy" for TV; and movies based on TV series (like Ranma ½, above).

When television arrived, it quickly took the place of movie series. In fact, many of those popular movie franchises ended up on TV in new adventures. But TV did not kill the movie franchise. James Bond, Rocky and American Pie (which has now shifted to video sequels) show the theatrical franchise is alive and well.

Direct- to-video animation began almost at the birth of home video. In Japan, studios realized that there was a great deal of demand for product to play on the Betamaxes and VHS players people were buying. The Japanese called them "OVAs," for "original video animation." The titles, which began to come out in the early 1980s, consisted of three general types -- productions based on manga productions that were too "racy" for TV and movies based on TV series.

In the U.S., video stores were booming due a growing rental market. Since much of Hollywood was still suspicious of the new technology, they were slow to offer product. At the time, most studio films were selling for more than $60. The stores, many being "mom and pop" outfits, were always on the lookout for affordable product to fill the shelves. Independent production houses began to make movies directly for the video market at prices less than the majors.

The year 1981 saw the release of Michael Nesmith's (of The Monkees' fame) Elephant Parts. It featured various music videos and comedy bits created specifically for the home video market. However, most direct- to-video releases were simply films that did not have the prestige or money to mount a theatrical release. Sometimes they were foreign films that could not find U.S. distribution. In year's past, such films might have only appeared at festivals or end up on TV. But with the growing video market, studios were finding they had an alternative to the theatrical field. For example, the 1988 horror sequel, The Howling IV, debuted on video.

By the mid-'80s, major studios moved into the sell-through market. Walt Disney sold Sleeping Beauty for "only" $29.95, which suddenly made buying movies a viable option for the consumer. © Disney Enterprises Inc. All rights reserved.

I should probably add a sidebar here about specialty markets. Just as old Hollywood made films specifically for blacks or small towns, some home video producers created product for a particular audience. One example was the market for religious themed videos. Just as these markets had religious themed books and comics, they also had animation. One of the most prominent might have been Hanna-Barbera's Greatest Stories from the Bible. Richard Rich, a former Disney animator who later made The Swan Princess (which itself had several direct- to-video sequels), had a lengthy career producing animated videos for the religious market.

By the mid-'80s, the major studios began to move into the sell-through market. Two early releases, Blade Runner and Walt Disney's Sleeping Beauty, were sold for "only" $29.95. That plus the entrance of Laserdiscs suddenly made buying movies a viable option. Still, much of the sell through from major studios were newer releases. The driving forces for home video production were basically adult and horror -- venues that could be produced inexpensively.

All this changed in 1994 when Disney brought out The Return of Jafar. Disney had already shaken up the TV business by bringing new and classic characters to TV. These series often began with a "TV movie" that was then cut into separate episodes. With Jafar Disney skipped the TV debut and went direct to the video market with this sequel to Aladdin. That same year, Disney's main theatrical competitor (Steven Spielberg) allowed Don Bluth's dinosaur feature, The Land Before Time, to be sequeled direct to video with The Land Before Time II: The Great Valley Adventure. Both were big sellers, and the animated sequel was off and running.

Special note should be made of The Land Before Time series. Originally debuting in 1988, this Don Bluth/Stephen Spielberg/George Lucas triage was a hit at the time, grossing nearly $100 million. The first "sequel" came out in 1994. Since that time, there has been a new release almost every year. 2007 sees the release of The Land Before Time XII: The Great Day of the Flyers. The success of this series has, almost more than Disney, made the U.S. direct- to-video sequel a popular asset to studios. One would need to go to Japan to find a series as successful.

With the first Aladdin and Land Before Time direct- to-video animated sequels, the direct- to-video production path was established. Both films had been handled via the same process of TV animation. Pre-production was handled in the U.S., but animation was farmed out to overseas operations. Despite the fact that many of these sequels ended up making as much money (via video sales) as theatricals did, studios preferred to keep these "major" productions in the TV animation mode. Some were given larger budgets. Some were handled by superior overseas studios. (Disney's Australia branch deserves mention.) However, even when the visuals were strong, too often the writing was still trapped in the realm of TV.

The home video business changed in 1994 when Disney released The Return of Jafar. Disney skipped the TV debut and went direct to the video market with this sequel to Aladdin. © Disney.

Now it should be mentioned that the animated sequel was not a new idea. A number of studios had created franchises in the area of shorts. But these were usually character driven. When Disney did a series of sequels to his hit short, The Three Little Pigs, he was said to exclaim, "You can't top pigs with pigs." But Walt never abandoned the idea of sequels or franchises. Fantasia was originally conceived as a franchise that would be released year after year with new sequences. Walt also spent time developing the literary sequel Bambi's Children. Both never went far due to the ticket sales of the originals. In live action, which was more cost effective, Walt freely accepted franchises. And, as mentioned, Japan gained fame for animated feature franchises, including Doraemon, Lupin III and Pokémon.

In 1996, Disney brought out a second Aladdin sequel, Aladdin and the King of Thieves. Bolstered with a campaign that advertised the return of Robin Williams as the Genie (Dan Castellaneta provided the voice in the video sequel and TV series), the tape sold very well. The year also saw the third Land Before Time show up at the top of sales charts. However, bigger news was the addition of a new major player using different rules. MGM/UA brought out All Dogs Go to Heaven 2.

Like Disney's original Return of Jafar, All Dogs Go to Heaven 2 was the springboard for an animated series. What made this production unique was unlike Aladdin and The Land Before Time, All Dogs Go to Heaven was not a box-office hit. In fact, it opened to mixed reviews and ended up with a "disappointing" box office of under $30 million. (In comparison, that year's The Little Mermaid grossed over $80 million.) The reason for the sequel was due to the huge sales figures for All Dogs Go to Heaven on home video.

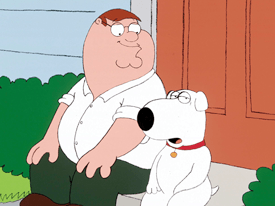

Suddenly home video execs realized that a top selling video was as big a launching pad as a theatrical hit. Since this realization, top selling home videos have led to many surprises. Video sales of the original Austin Powers feature were strong enough to warrant a full-blown theatrical sequel. The sales of Family Guy on home video led to the cancelled TV series being revived. Meanwhile, animated theatrical "disappointments" including Ferngully (1998 sequel), The Brave Little Toaster (1997 and 1998 sequels), The Secret of NIMH (1998 sequel) and Balto (2002 and 2004 sequels) all gained new life via direct- to-video features.

Top selling home videos have led to many surprises. Video sales of Family Guy led to a renewed life for the cancelled TV series. © and 1999 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp. All rights reserved.

Studios and execs now looked everywhere for sources of animated sequels. 1998 saw Universal release Hercules & Xena -- The Animated Movie: The Battle for Mount Olympus, which featured characters from the two popular syndicated series. Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and the Island of Misfit Toys (2001) was based on the popular puppet animated TV special of the '60s. In 2004, Warners' live action Kangaroo Jack had an animated sequel while Universal's Van Helsing got an animated prequel. The year 2005, FOX pulled its TV series Family Guy for Stewie Griffin: The Untold Story. The live action-CGI Stuart Little series went fully animated with 2005's Stuart Little 3: Call of the Wild.

Meanwhile, Disney continued to mine its film library. At times, some of these sequels ended up getting released theatrically first, such as Toy Story 2, Jungle Book 2 and Peter Pan: Return to Neverland. While Toy Story 2 was a blockbuster, others did less well. Not wanting to risk a box office backlash, Disney dropped the strategy. More recently, studios have begun debuting productions on both video and cable almost simultaneously. Productions that aired on cable just days before the video sold in stores turned that airing into an infomercial.

Warner Bros. joined this fray with "longform" versions of several Kids' WB! and Cartoon Network series, including Dexter's Lab, Foster's Home for Imaginary Friends, Camp Lazlo and Teen Titans. On top of that is a seemingly never-ending parade of direct- to-video features starring Hanna-Barbera classic characters including Scooby-Doo and Tom and Jerry.

Today, a key source for direct- to-video franchises comes from the merchandising world. Barbie, Bratz, Care Bears, Strawberry Shortcake and various Marvel Comic characters are all enjoying a successful series of animated programs created for the direct- to-video market. Many of the newer sequels are utilizing CGI production due to the belief that today's young audience prefers the look.

A recent key source for direct- to-video franchises comes from properties like Strawberry Shortcake.

Despite the grumblings of those who feel theatrical sequels cheapen the original, there are instances of a franchise with many quality entries from Tarzan to James Bond to Star Wars. And there are even times when a sequel surpasses the original at box-office like Aliens and Toy Story 2. Yet these are the exceptions. Generally, the box office for a sequel is around 60% of the original, so a theatrical sequel is budgeted at a lower price tag than the original. And the budget for video sequels is even lower.

But no matter what one thinks of sequels, as long as they continue to make money at the box office or on the video sales charts, they are as inevitable as new video formats. In fact, some have already designated the summer of 2007 as the "summer of sequels," with such films as Spider-Man 3, Shrek The Third, Pirates of The Caribbean: At World's End, Hostel 2, Oceans 13, Fantastic Four 2, Evan Almighty, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, The Bourne Ultimatum and Rush Hour 3 all set to debut. And that doesn't count the films based on popular TV shows (like Transformers and Underdog) hoping to turn into new franchises. It seems nowadays, familiarity breeds content... on the big and small screen.

John Cawley is a producer of animation whose résumé includes Cartoon Network, Nickelodeon, New World/Marvel, Film Roman and Sullivan-Bluth. John, an author of several books on animation, has also written for comics and animation. He is a lecturer on animation production and an established mascot performer.