Since entering animation in the Seventies, David Ehrlich has created not only a prolific number of films but also a greater sense of the animation community. Chris Robinson explains. Includes QuickTime clips!

David Ehrlich. Photo credit Amanda Weatherman.

Editor's Note: If you have the QuickTime plug-in, you can view clips from selected films where indicated.

"It's all error... There's only error. There's the heart of the world. Nobody finds his life. That is life." Philip Roth I Married A Communist

American animator David Ehrlich lives in the woods, but he's not lost like Dante, for he knows his way as well as any of us can. These Vermont woods offer Ehrlich a modicum of harmony through their indispensable songs of nature. Films like Vermont Étude (1977) and Dance of Nature (1991) evoke these natural melodies and their mysterious cyclical routes, but more so, his life and all its borrowed breaths are rooted in the same uncertainty, ugliness and beauty. His images are restless and at times it's as if they, like Ehrlich, are in search of their life; a life that fits; a life that unleashes the soul from confusion, anger and frustration.

View Taking Color for a Walk, one of Ehrlich's two new films. It was presented at the Ottawa International Animation Festival where Ehrlich, subject of a career retrospective, also served as Honorary President of the Festival. © David Ehrlich.

View Taking Color for a Walk, one of Ehrlich's two new films. It was presented at the Ottawa International Animation Festival where Ehrlich, subject of a career retrospective, also served as Honorary President of the Festival. © David Ehrlich.

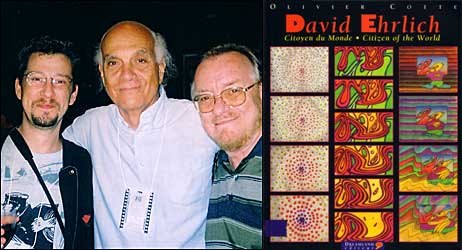

This year, at least, life appears to fit David Ehrlich just fine. In May, Dreamland Publishing in France released David Ehrlich: Citizen of the World by scholar Olivier Cotte. In June, Ehrlich received the prestigious ASIFA Achievement Award at the Zagreb Animation Festival. And in October he served as Honorary President for the Ottawa International Animation Festival alongside a retrospective of his work, which included not one, but two new films: Taking Color For a Walk (2002) and Current Events (2002). Not a bad year for ANY independent animator let alone an experimental one.

So okay fair enough, this guy got some nice accolades, but who, you ask, is David Ehrlich? First and foremost, Ehrlich is an independent experimental animator. He's been making almost one film per year since 1975. His most acclaimed works include Precious Metal (1980), Dissipative Dialogues (1982), Dryads (1988) and A Child's Dream (1990). Since 1992, he's been teaching animation at the ol' Animal House stomping grounds at Dartmouth College, and since the mid-1970s, he has taught numerous children's workshops around the world. From 1988-2000, Ehrlich was an Executive Board member of ASIFA International.

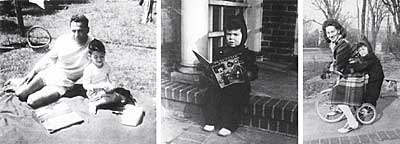

Left to right: David with his father Max in 1946; David as an early reader; and with his mother Jeannette in 1943. © David Ehrlich.

David experiments with multimedia performance while teaching at SUNY and living in New York City in 1971. © David Ehrlich.

Animation and Ehrlich

Ehrlich was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey in 1941. His pops, Max, was an eye surgeon and his mom, Jeannette, raised David and his younger brother, Jeff, and wrote poems in between. As a youth Ehrlich did the things boys were supposed to do (boxing, football) and not supposed to do (draw, paint, sing and tap-dance). He began pre-medical study at Cornell but soon realized that he was taking this road for his parents not for himself and switched to pre-law where he also breathed in courses in international relations and a boatload of Eastern languages and philosophy. His interest in all things Eastern led him, like many after him, to visit India where he apprenticed as a sculptor and studied a sitar like instrument called the veena. Perhaps afraid to get on with life, Ehrlich continued to study after he returned to the U.S.A. in 1964. By the 1970s, he became increasingly interested in the process of creativity and even taught courses on the subject at the State University of New York from 1971-75. All the while Ehrlich continued to paint, sculpt, compose and dance. Animation emerged out of a desire to integrate these different arts and around 1974, he began toying around with an 8mm camera. By 1975, he made his first animation film, the aptly titled, Metamorphosis. He was hooked.

In 1977, Ehrlich began sending his films [Vermont Étude (1977) and Robot (1977)] to ASIFA festivals (Annecy and Zagreb). Incredibly, given the amount of activities and initiatives Ehrlich undertook he was in essence a shy guy. Fortunately, animation has always been dominated by open, modest, faulty and caring human beings. Ehrlich was quickly welcomed into this new world and specifically the International Animators' Association, ASIFA.

Robot (above) and Vermont Étude (left), both made in 1977, were Ehrlich's entrées into ASIFA. See a clip from Vermont Étude now. © David Ehrlich.

Ehrlich had joined ASIFA-East (New York chapter) in 1975, but didn't become formally involved on an international level until 1982 when he became part of the ASIFA Workshop Committee. (By the way, during this time, Ehrlich, motivated by his father's struggle with colon cancer, researched and wrote a book about bowel health called The Bowel Book.) Beginning in 1985, he co-chaired an ASIFA committee on International Cooperation (remember this was Cold War days) and two of his great initiatives were the collaboration films Academy Leader Variations (1987) and Animated Self-Portraits (1989). The first film featured a series of leader interpretations by artists from Poland, U.S.A., Switzerland and China, while the second featured a series of self-portraits from U.S., Czech, Estonian, Japanese and Yugoslav animators. Both films went on to win a variety of awards including a Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival for Academy Leader Variations.

ASIFA Undertakings

In 1988, Ehrlich was elected to the Executive Board of ASIFA and served as Vice-President from 1991-1997. In 2000, he retired from ASIFA. During his tenure, Ehrlich was the conscience, voice and legs of ASIFA. While he was never elected President, he was always ASIFA's leader serving as an active bridge between Eastern and Western artists, and as an often-vocal defender of the rights of animation artists.

Ehrlich's support of 'less fortunate' animators was not limited to words. In 1982, he started the Vermont Visiting Animators Program to bring international animators to do children's workshops in Vermont. Ehrlich then arranged additional screening tours in places like Montreal, New York and New England. The list of animators is astounding: Yuri Norstein, Priit Pärn, A Da, Piotr Dumala, Jerzy Kucia, Michel Ocelot, Borivoj Dovnikovic and on and on. Even more amazing is the fact that from 1984 onwards, Ehrlich funded the visits himself. His motivations were manifold. It gave him a chance to hang out with some friends and was a way of, in his words, "opening up naïve, unexposed Americans to different cultures and socio-political systems." The program, which he stopped in 2001, was a success and eventually expanded to California via ASIFA-San Francisco and ASIFA-Hollywood.

See Precious Metal (1983), an example of Ehrlich's "scientific" work. © David Ehrlich.

See Precious Metal (1983), an example of Ehrlich's "scientific" work. © David Ehrlich.

Work for Within

As an artist, Ehrlich is like a Pre-Socratic philosopher, convinced that the essence of life is to be found in the materials of nature (fire, water and air). Throughout his work, Ehrlich sorts through the wreckage of the collision between the individual and society, space and self. Even in his most 'scientific' films like Precious Metal, Precious Metal Variations (1983), Point (1984), Pixel (1987), Interstitial Wavescapes (1995), and all those other dots, lines and circle type films, there remains a strong connection to the material world of Ehrlich's existence. This is what, for me anyway, elevates him above the cold world of formalism or structuralism or whatever friggin 'ism' 'you' want to use.

Echoing another fine experimental artist, Rene Jodoin, Ehrlich sees the sights unseen by most of us. He recognizes the subtle effects that time and space have on our (and his) daily lives, and the routines we create within them (e.g. Robot Rerun, Dissipative Fantasies). Whether it's trees (Dance of Nature), bees (Point), women (Dryads, Dissipative Dialogues), or himself, life is always flowing, expanding, contracting, evolving and, most importantly, interconnecting. Potential is the only certainty.

Dissipative Fantasies knocks down the walls between the individual and society. © David Ehrlich.

In films like Dissipative Fantasies (1986), Ehrlich shatters the gap between him and us. 'We' are implicated in everything that contacts us. Ehrlich not only shows us the world he sees, but also the eyes with which he sees, the ears with which he hears, and the hand with which he feels. For Ehrlich, the separation of individual and world is simply not possible. All is personal and political.

Until 1991 (when he suffered temporarily from a blepherospasm, which diminished his sight, and he began working tactilely with clay painting animation), Ehrlich's films were entirely drawn by hand using prismacolour pencils and later ink markers (Pixel and Point). Visually, colours dominate the films. They're an integral part of any understanding of his films. Using a 12-tone system (or for you laymen like me -- sorta like a single colour colourbar), Ehrlich's expressive, powerful and varied colours not only capture the external flavour of the world around him, but also an internal and deeply personal sense of joy, hope and harmony that is at the core of Ehrlich's humanistic being.

Another acclaimed work, Dryads, explores the subject of women. © David Ehrlich.

If you look through the back of the Citizen of the World book, there are a variety of tributes to Ehrlich from many animators. Most of these tributes speak of Ehrlich's character and seem to avoid dealing with his films. For a variety of reasons, some people (especially fellow animators) are very shortsighted when it comes to Ehrlich's work. Perhaps there are those who cannot get beyond the visual style which often seems like a leftover ode to the psychedelic blots of hippie culture (but in fact is more rooted in Chinese art). Certainly, the 12 tone colour scheme (picked up from serial and Indian music) that Ehrlich uses often looks like a remnant from an acid trip circa Jefferson Airplane. Furthermore, the animation, especially in early films like Robot and Precious Metal appears hesitant, awkward, downright slow (we post-Sesame Street kids expect animation to be fast and seamless). Ehrlich also happens to make non-narrative works in a narrative world. But perhaps the biggest obstacle is rooted in economics. These are big films made with small material means. These are one man films made using pencils on paper and as such they (especially the early 16mm films) have a very raw, primitive appearance (i.e. cheap). All these criticisms are understandable but superficial. And fortunately, it appears, given the long overdue recognition that Ehrlich is receiving this year (his films are also available on video), that the shortsighted are in the minority.

Ehrlich greets Olivier Cotte, the author of David Ehrlich: Citizen of the World (left) and animator Borivoj (Bordo) Dovnikovic in Zagreb (2002). Photograph © David Ehrlich; book cover: © David Ehrlich and © Dreamland

A Child's Dream (1990) helped establish Ehrlich's reputation as a premier experimental animator. © David Ehrlich.

Ehrlich's films are beautiful, complex and passionate excavations of a flawed soul who seeks, like we all do, a harmony or rhythm. Ol' Chuck Olson once said, "He who controls rhythm, controls." Ehrlich's work is a means of articulating the tuneless tensions in order to find that groove that we all need to ride through life comfortably. Ehrlich's films, like his life, sometimes fail, they succumb to redundancy, and occasionally the GRAND softie in him creeps too strongly into his work and pushes aside the calm quiet of wisdom. But failure, error, it's all life. Yet defeat is momentary. Ehrlich doesn't pitch a tent stake in the ground. He gathers his strength, mends his aches, soothes his ego's sorrow, and gets right back into the game. Led by the same stubborn determination, he resumes his struggle all over again. The sun is new again, each day.

The video Animation by David Ehrlich is available from www.facets.org. The book David Ehrlich: Citizen of the World is available from www. upne.com.

Chris Robinson is the artistic director of the Ottawa International Animation Festival and the Ottawa International Student Animation Festival. He is also the editor of the semi-annual ASIFA Magazine. Robinson has curated film programs and served on festival juries throughout the world. He writes a monthly column ("The Animation Pimp") for Animation World Network and has written for Salon.com, Cinemascope, Take One, 12gauge, City Pages and others. Robinson contributed a chapter on English-Canadian animation to the book, North of Everything: English-Canadian Cinema Since 1980. He is currently working on two books: Between Genius and Utter Illiteracy: A Story of Estonian Animation (March 2003 by Varrak Publishing) and a biography of an ex-hockey player, Doug Harvey: Like There Was No Tomorrow (Spring 2004, Boheme Press).

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 1581-robinson02colorwalk.mov | 1.76 MB |

| 1581-robinson07vermontetude.mov | 1.76 MB |

| 1581-robinson10preciousmetal.mov | 1.76 MB |