Disney’s new BRDF lighting system stands front and center in the array of new tech tools anchoring the studio’s animation production pipeline.

It’s difficult not to be taken aback by the stunning visuals of Disney’s latest animated feature, Wreck-It Ralph. To quote Billy Crystal’s from the famous SNL sketch, “You look maavelous.” While most studios claim to “push the envelope” on every project, few actually do. In Disney’s case, CTO Andy Hendrickson’s push to develop innovative and enabling digital tools has given the studio’s artists an unprecedented technological playground in which they have created a truly spectacular animated film. According to Hendrickson, “’Wreck-It Ralph’ is one of the most complex films that we’ve ever made here at Disney. Getting the best images on screen requires the best technology. Quality is our business plan, so we’re all about creating new technology to support the art in the best way. It’s that mixture of art and technology that you see on screen. It’s one of those things that has always set Disney animated films apart.”

For Wreck-It Ralph, in addition to refinements in the production pipeline and a new virtual cinematography Camera Capture system that let layout artists and the film’s director, Rich Moore, literally walk through scenes in real-time, visualizing various takes and virtual camera moves, Disney implemented BRDFs, or bidirectional reflectance distribution functions, a brand new lighting system based on a new idea of how surfaces react with light in a physically based, realistic or theatrical way. As Director of Look and Lighting Adolph Lusinsky explained, “Disney’s BRDF is a marriage of the way a surface reacts and the way a light illuminates the surface. It’s completely different from the way lighting has worked on any of our previous shows.” According to Lusinsky, with the old shader system, lighters had to cheat to get things to look believable. With BRDFs, you get a much more believable look in the way light reflects off of and rolls over a surface. “At Disney, we want to be able to achieve a result that looks physically believable and accurate, but then we want to be able to art direct it too,” he continued. “It lets us get an image that’s very Disney.”

In discussions with Lusinsky, Look and Lighting associate director Brian Leach, FX supervisors Cesar Velazquez and David Hutchins and VFX Supervisor Scott Kersavage, they shared insights into tackling the challenges faced creating the numerous “worlds” where the story takes place.

Lights, Camera, Fudge!

As previously mentioned, Disney built a new lighting and shading system for the film from the ground up. Their principal engineer Brent Burley went back to the basic science of light interacting with real materials to derive an entirely new algorithm for a more realistic, more reality-based lighting look on materials. Studies on surface lighting for over 100 materials were performed as part of the research that went into the new system.

BRDFs mean fewer lights are needed overall and fewer pinpoint lights are needed to hit specific areas to mimic more accurate reflections and make them look good. Now the light reflects in a more physically-based manner. The results look much more real.

One of the biggest challenges the new lighting system faced on Wreck-It Ralph was making food look believable and more importantly, making it look delicious. Though extensive research was done for each world, the largest amount was done for Sugar Rush, which represents 50% of the movie. Making an entire world out of candy is unique and poses tremendous visual challenges in order to make everything look real and tasty as well. Like on most animated films, the team needed reference materials for study.

So, the visual development group traveled to the world’s largest candy fair, the annual ISM Cologne in Germany, just to immerse themselves in different types of candy from around the world. They were surprised by the detailed lighting used to highlight the confections. Some candy was even showcased in special displays, lit with small pinpoint spotlights, like pieces of jewelry, dazzling with little glints and reflections. They traveled to a See’s Candy manufacturing facility to see firsthand the dynamics of a huge candy making plant, marveling for example at how marshmallow is moved around from one place to another on conveyer belts running high above the heads of administrative staff. They visited bakeries and other facilities where large volumes of food were made, packaged and processed.

Additionally, the team brought in a number of food photographers to see how they lit their shots. As Leach explained, they were trying to learn how to make food look delicious, what they should try to achieve and what they should try to avoid. One key was the issue of broad specular reflections, being able to see into the shadows, trying to use warm colors so the food looked tasty and inviting.

They pored over two types of food photos – images of food they wanted to eat and images of food they didn’t want to eat – to analyze what made the food look appealing, or not. Visually, people want to know what they’re eating. They noticed the use of saturated dark values, how photographers didn’t want to let things get too black or grey. They learned to lean towards using soft light, getting nice broad specular highlights, being very careful with hard light, avoiding ambiguous textures and distracting shadow shapes that become more interesting than the food. They learned that the best food images show various pieces with clear, distinct shapes that don’t run together. You can tell what everything is in the food.

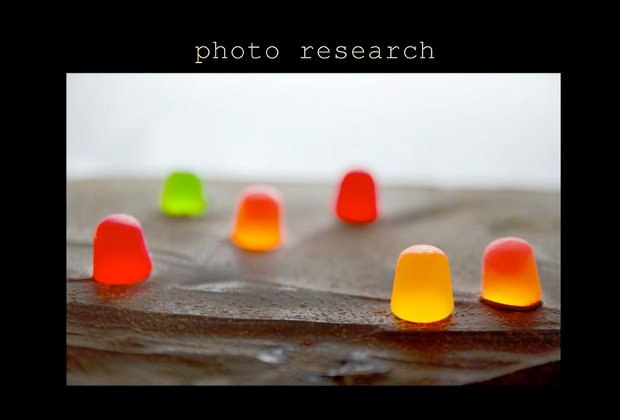

Next the lighting and effects teams setup a photo lab right in the studio, where they photographed various foods to provide artists with accurate reference materials. They focused on determining what type of lighting gave the most appealing look. They played with polarizing filters to separate out reflection versus refraction. Leach described it this way. “For example, we have dungeons that are made out of sugar cubes. We wanted to see what those looked like. Tests were done way before any models were built. Or what would chocolate mountains look like with self-illuminated gumdrops?” There’s a scene in the film where Ralph crashes a ship into a candy cane forest, sliding through frosting before finally coming to a halt. For Leach’s test, he just grabbed a toy ship and dragged it through a bunch of cake frosting. The results were surprising - the team found some nice elegant shapes that they didn’t expect. “It was one of those happy accidents,” said Leach. “We got some really appealing shapes in front of the ship which we weren’t expecting, which really helped with the final modeling.”

A Little More Taffy on the Lower Lip Please

Early on, the FX team started looking at the story to determine the variety of effects needed for the film. They quickly determined Wreck-It Ralph would require more effects than any animated film they’d done before. The team focused primarily on the three main worlds, how they wanted them to be different, not just in animation and layout but in effects.

Velazquez described the overall FX mandate that came down from Moore and John Lasseter. “Rich Moore and John Lasseter challenged us to make the effects from each of the worlds unique, so that when you look at smoke or dust, you can tell if it’s from Sugar Rush, Hero’s Duty or the Nicelander’s world. They wanted us to add character to an explosion or any kind of effect, making it feel like it belonged in that particular world.”

They worked with art director Mike Gabriel to determine the rules of how effects should be handled. The 8 bit world of Niceland needed simple shapes and motion. Sugar Rush required more classic animation – cartoony fun, charming effects, smoother lines. Those worlds sharply contrasted with Hero’s Duty, where things needed to look as real as possible.

The 1980s 8-bit arcade game design of Niceland required stylized effects that exemplified sprite-based video games. For example, the smoke incorporated repeating patterns, with simplified rectilinear shapes and pixel-like cubes. A scene with fire in a fireplace used a looping pattern and staccato movement. 2D effects animators were brought in to help design the splat from a cake Ralph smashed with his fist.

The 1990s, cartoony design of Sugar Rush required things look cute and charming. And of course, since everything in Sugar Rush is food, everything had to look delicious. So for example, cotton candy clouds had to be made into 3D volumetric elements to match the matte paintings from the background department. Dust and smoke from race cars were styled like patterned frosting decorated on a cake with a pastry bag. When Ralph fell into a pond of taffy, FX artists gave him a nice umbrella splash that evokes the classic Disney animation of Alice in Wonderland. For the taffy stuck on Ralph’s mouth that stretched between his upper and lower lips, the FX team tried simulations but didn’t feel they looked realistic. They detracted from the animation. So, they had a 2D artist add different taffy effects to make it look more believable.

When it came to the world of Hero’s Duty, they were tasked to make it as different and real as possible. That involved lots of layers of subtle effects to give a realistic feeling of the atmosphere, the fog of war. This meant different types of smoke, steam, weapons muzzle flash, putting debris in the air like Saving Private Ryan, placing items in constant motion, all the little things in the background that will lend realism to the sequence. Ultimately, the focus was giving the audience the feeling they were really in a first person shooter game.

So Many Effects, So Little Time…and So Many Challenges

According to Kersavage, there were so many varied effects on the film, you never knew whether or not a simulation would work until you tried it. “There were so many stylized effects in this film. The nature of effects, it’s always trial and error. We always try to use a simulation but ultimately, if it didn’t give us the look we were trying to achieve, we would incorporate a more hand drawn 2D effect.”

New to this film was the role of the effects designer. As Velazquez explained, software that comes out of the box today is designed to make things look real. That’s not necessarily what they were going for. “We wanted stylized effects. We have such a strong legacy in 2D that we ended up with a number of 2D effects animators working with the CG effects animators to help with timing and shapes, tuning the simulations. They would draw over the CG effect to show a more stylized way it would be done in 2D.”

While all the lighting and FX work was challenging, the teams spent the most time with Sugar Rush. It all boiled down to the fact that everything had to look like food. As Leach explained, “One big challenge, when we think of food, we’re used to seeing it presented as a single thing on a plate. You’re looking at is as ‘here is this thing I’m going to eat.’ When we turned it into a world where everything surrounding you is food, that made it more difficult to have it look yummy like we’re used to but at the same time, be presented to you in the context of an environment of trees and a ground plane I’m walking on.”

Scale was also big issue. Leach described how when you take cocoa powder or cake crumbs and turn it into an entire ground plane, your brain looks at it and thinks it’s just sand or dirt. That’s what you’re used to seeing, what you normally walk on and interact with. That’s your normal visual perspective, your frame of reference in the world around you. According to Kersavage, “This thing you’re used to looking at hanging on your Christmas tree is now a giant tree. We knew immediately when we were setting up cameras, ‘Wow, how are we going to get this to feel as vast and enormous as we want it to feel?’”

The iterative nature of the lighting and effects work meant change was inevitable as the film progressed. As Velazquez explained, story drives all the work and as it evolves over time, and at various points, there are markers, or “story drops” where things get issued into production as “good to go,” less likely to change. From here, all the assets can be readied for animation, camera move, lighting, texturing etc., and made ready to go. However, assets can change at any time as the story changes and as they are further refined and made to look better. “At the end of the day, you want the best work up on the screen. We’ve created a process at Disney where we can do a lot of iterations over time, rendering over and over and over again. Our renderfarm doubled in size over the course of this film and it helped us put a better film on the screen.”

Lusinsky remarked, “Our work was an iterative process. Many of the worlds we started off with are not in the movie any more. You see what sticks and what doesn’t. As you move forward, you have a better idea of what the story is going to be and things get better and better. This studio is really about pushing the limits as far as we can. If better ideas come up, in story or lighting and effects, we want to support making it better to the very end.”

“In the world of Sugar Rush, I love the way we were able to light all the food,” Lusinsky continued. “It looks spectacular and yummy. It was challenging to make everything look yummy and still get the cinematic lighting beats that we need to tell the story. The new BRDF allowed us to use translucency to get a gummy look, as well as a refractive shader for more of a Jolly Rancher candy look where you can see behind it. For other materials, we were able to see bubbles floating inside the medium. We’ve never been able to do anything like this before at the Studio.”

Hendrickson concluded, “I’m really proud of our BRDF breakthrough on this film. We wouldn’t have been able to make four distinct worlds economically without it. We would have had to curtail the creative ambition of Wreck-It Ralph and that is against the very essence of Disney. I’ve never seen another animation company do it as exacting as we do.”

--

Dan Sarto is Editor-in-Chief and Publisher of AnimationWorld.

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.