Once upon a time animation art wasn't worth the celluloid it was painted on. Art that would now be worth tens of thousands of dollars was washed or thrown away – and what was saved often handled thoughtlessly or just forgotten about. Things have changed since then, changed a lot. People now realize that animation art is exactly that - a thing of beauty in its own right, and a cultural heritage to be cherished and preserved. Preservation is where Ron Barbagallo comes into the picture.

Once upon a time animation art wasn't worth the celluloid it was painted on. Art that would now be worth tens of thousands of dollars was washed or thrown away – and what was saved often handled thoughtlessly or just forgotten about.

Things have changed since then, changed a lot. People now realize that animation art is exactly that - a thing of beauty in its own right, and a cultural heritage to be cherished and preserved. (The fact that original cels, concept art and similar items are high-valued collectibles that are transitioning to museum art hasn't hurt either.)

Preservation is where Ron Barbagallo comes into the picture. Even the most carefully preserved original art cannot escape the inevitable decay of the materials that went into its creation, and clients on the order of the Walt Disney Co., Warner Bros., Hanna-Barbera and even individuals like Roy E. Disney have turned to Ron's Animation Art Conservation practice for rescue and restoration projects that often border on the miraculous.

Ron's been at it for nearly 25 years. While his work has focused on the preservation of hand-painted cels and backgrounds, his work also includes physical objects like Mary GrandPré's Harry Potter pastel art book covers, Batman's suits from the Tim Burton and Christopher Nolan movies and a four-year preservation effort for the long-term care of Burton's Nightmare Before Christmas, Corpse Bride and James and the Giant Peach puppets. Ron's skills have even led him to the shattered remnants of the World Trade Center.

"There is no one in the field that I trust more than Ron," enthuses Elyse Luray, formerly Christie's animation expert and host of PBS' History Detectives. "His knowledge of the science behind the paint, cels and material used in early animation is unparalleled."

You were one of the conservators who worked at Ground Zero; how did that come about?

I remember standing by the twisted metal beams that once held World Trade Center: Tower One, looking around the wreckage in Kennedy Airport's Hanger 17 and being moved that my work led me here. I spend most of my day peering through microscopes at vintage Disney cel paintings and backgrounds and obsessing over areas smaller than 1/8th of an inch. The last time I had been at what we call Ground Zero was to visit my mother while she worked at the Port Authority of New York/New Jersey.

I never imagined that my work in the preservation of Disney Animation Artwork would lead me here. Now, I was working among of a team of conservators, who like Steven Weintraub, the legendary environmental preservation and conservation consultant overseeing the main 9/11 preservation effort, were brought in to care for everything from vehicles to steel. The reason for my being there was my experience in the preservation of plastics that contained hand-painted or printed media. I was hired by the Warner Bros. Studio to consult on their retail store artifacts from under WTC Tower One.

How did your interest in art preservation come about?

While studying Fine Art and Animation at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan, I had an unusual interest in the stability of my materials. While a lot of the other kids at SVA, like Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf and faux-student Jean-Michel Basquiat were content to throw paint haphazardly on everything from canvas to bathroom stalls, I was reading Ralph Mayer's The Artist's Handbook and found ways to gesso panels with increasing amounts of distilled water to get a smooth finish or ways to get oil paint to adhere to glass sheets used for Matte Paintings.

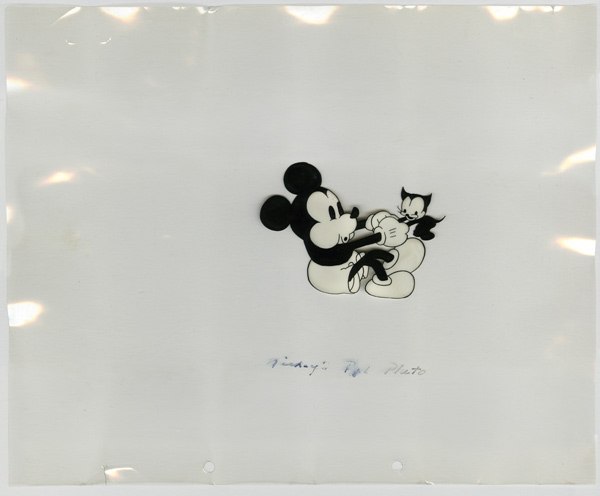

In 1987, my twin sister Lori and I purchased a White Rabbit cel painting from Disney's 1951 animated film Alice in Wonderland. Lori died before the cel arrived and when it did, I noticed it was damaged. Someone put Wite-Out on in his hind paw. I tried to find someone to remove the Wite-Out and do a reversible fill and learned that there were only 'restorers' who would remove the original paint and replace it with new paint.

That led to me to acquiring books from the Yale Library and partially repairing the art myself. Afterwards, the authorized Disney galleries heard about my ability to do partial repairs and things took off from there. Whether creating preservation guidelines for art or doing partial repairs, I feel like a part of me is still fixing that White Rabbit cel.

Your work seems to draw on both scientific and aesthetic backgrounds – left and right-brain skills as it were. How do these 'halves' of your brain work together?

The science has been ongoing. Shortly after starting this work, I did a series of physical and thermal property tests on the paints and on vintage cel sheets. I also hired conservation scientists, like Michele Derrick, to do the extensive scientific testing of the paints, nitrate and acetates and post-production materials used to make Disney Animation Art.

Physical exploration included determining why the paints pull away from parts of the plastic and a study of the signs of warping, yellowing and other distortions that occur as the cel sheets as they age. For over two decades and from nearly all their features and many of their shorts, Michele and I continue to log the degradative evolution of Disney's cels and paints, not only their individual chemical breakdowns but also their degradation under different environmental conditions. This work doesn't just cover art from Disney; it includes and cross references a wide variety of Warner Bros., MGM, Simpsons and Hanna-Barbera animation art as well.

The anniversary of Roy E. Disney's death was this past December. How did your relationship with him begin?

The Disney Animation Research Library asked me to work on six of Roy's cels and backgrounds. There was a photo shoot that was supposed to happen in Roy's office in the newly finished Feature Animation building and this art was needed for that photo-op.

Then the Disney Animation Research Library gave me concept art, production cels and backgrounds, and before I was asked to work on them, was asked to stabilize a cel and background that was experiencing rapid loss of acetic acid and plasticizers. From what I understand this is the first time museum level conservation science was applied to the ARL's collection. I also did a lot of writing which included: Cellulose Nitrate and Cellulose Acetate Storage Recommendations, a Mission Statement, Care of Collection Policies and Guidelines for a Procedure's Manual. My aim was to help alter a warehouse of commercially stored production art into a state-of-the-art facility that cared for its art with long-term goals based upon my intimate knowledge of the materials.

Afterwards, Roy and I maintained a dialog and in 2008, before he let me know he was ill, called me into his offices at Shamrock [Holdings, the Disney family's investment firm] and asked me "to revisit his collection" one last time. I was working on a number of pieces of Disney art from private collectors, creating micro-environments for sensitive art from Harry Potter and a preservation study of Tim Burton's puppets from Nightmare, Giant Peach and Corpse Bride, but given all he had done for me, I made time for Roy's work.

One of your recent projects was a four-year preservation project to uncover the degradative causes for the deterioration of Tim Burton's puppet characters. How did this come together?

While doing research at the Walt Disney Archives back in the 90s, I noticed the James and the Giant Peach puppets were experiencing a different type of degradation than the Nightmare Before Christmas puppets I had previously examined at the Disney ARL. When Warner Bros. had me examine their Corpse Bride puppets, I noticed yet a third type of deterioration. This was an opportunity to do for Tim's puppets what I did for the Disney, Warner Bros., Hanna-Barbera animation art. Some of the project was complex; some of it puzzling -- but the one quality Michele and I share is fortitude. Neither of us gives up until the work is finished, no matter what has to be rethought.

What are the specific challenges of preserving physical objects like Burton's puppets as opposed to two-dimensional art?

It's less of a two-dimensional vs. three dimensional issue, although oddly enough, gravity did come into play with the Corpse Bride puppets. With Disney cels, there is the perpetual problem of media becoming airborne and their environment making things complex. With the puppets, the paint layers are often thinner than the Disney paint layers, and at times the paint for the puppets is added directly into the plastics.

The puppets are a mixed-media artifact - with the puppets from the earlier films being more simplistic in their construction and the Nightmare Before Christmas puppets being the ones most in danger of degradation from uneducated care.

With your knowledge of the deterioration of painted plastic objects and art, what aspects of their future preservation concern you the most?

The biggest problem is getting executives to break from running a Hollywood Studio so there is time to guide them that the 'inanimate' objects in their collections are actually very animated chemically; and tangibly speaking, the other problem is – money. Hollywood is a content making and licensing industry. Budgets for preservation is not necessarily a first thought. With so many museums exhibiting animation art and the cels and backgrounds getting older, at some point, the historical significance and their licensing value will meet. That's my hope anyway.