Andrew Osmond chats with Lloyd Price, supervising animator on Wallace & Gromit: Curse of the Were-Rabbit, about bringing Aardman superstar plasticine duo to the big screen.

As the eagerly-awaited Wallace & Gromit: Curse of the Were-Rabbit opens in cinemas, AWN speaks to three of the films staff about bringing the worlds most beloved clay heroes to the big screen. Lloyd Price is supervising animator on the film, responsible for, in his words, training animators in the ways of Wallace & Gromit, as they came onto production. Chris Sadler is lead animator on the villainous Victor Quartermaine; he and Price teamed as co-directors on the Cracking Contraptions series of Wallace & Gromit shorts made in the run-up to Were-Rabbit. Finally, director of photography Dave Alex Riddett isnt only a veteran of Aardman for two decades, but one of the original co-founders of Bristols neighboring bolex brothers studio, whose work ranges from the pixilated Secret Adventures of Tom Thumb to the CGI Magic Roundabout.

Aardman resisted the pressure to make a Hollywood movie with Wallace & Gromit: Curse of the Were-Rabbit. All images courtesy DreamWorks Animation SKG © and Aardman Animations Ltd.

Andrew Osmond: What are the main differences between making the earlier half-hour Wallace & Gromit films and making a feature-length adventure?

Lloyd Price (supervising animator): In the case of A Close Shave, the third of the half-hour Wallace & Gromits, Nick Park and Bob Baker pretty well wrote the script, drew the boards and we effectively shot what they had done. There were very few changes in A Close Shave the scenes where Wallace was reading newspapers with the sheep came later, but that was about all. But when you make a feature film like Curse of the Were-Rabbit, theyre such big things and so much is riding on them that the script is in a constant state of flux. Things are being changed, ideas are being put in and taken out, and you generally end up starting work on the first act because thats in the best shape. The third act was still in flux well into production, with little tweaks literally into the last five or six weeks of shooting. [Directors Nick Park and Steve Box did the bulk of the film story, although Bob Baker came up with the idea of a Were-Rabbit.] Because youre working with a DreamWorks and they like showing parts of the film to selected audiences, theres always pressure to adjust and change things

Key animator Jay Grace works on one of the 33 miniature sets on the floor of Aardmans feature studio in Bristol.

AO: How do you respond to the fans fear that the pressure of a Hollywood feature film will make this a less pure, personal animation than the previous Wallace & Gromit films?

LP: Nick insisted that he had creative control. That was incredibly important, not only to Nick but everyone at Aardman. People can look at the film from the outside and point out something and say, this is obviously an American influence, and they go on about some of the references and things like that, but theyre dead wrong they absolutely came from Nick and how he works. The film cant not be influenced by other things, but its still very much the film that Nick Park and Steve Box wanted to make especially Nick, because he sees Wallace and Gromit as almost like his children. While Aardman was constantly bombarded with advice and ideas from DreamWorks, the criterion was it was taken on board if it was a good idea, as it would be if it came from Aardman people.

AO: Tell us about the characters in the film.

LP: Of the heroes, I think that Gromit is the deeper, more interesting character. Wallace is the one who gets into trouble, while Gromit is the one who sorts things out and gets things done. This time, hes got to go through a whole feature without speaking, so the demands on him in terms of the range of emotions are a lot harder. Youve really got to get inside him in his shots. Youre always reading his face, his eyes and brows and ears, the angle of his head.

With this movie, the filmmakers emphasized the charm of a handcrafted, textured look. In Chicken Run, the characters were very slick and smoothed down.

The performance comes from talking to the directors, and acting out things yourself to get the subtleties of the performance. Youre trying to get the shots right first time, first take. To be honest, the animation process is almost secondary. When youre slogging through 10 hours a day, moving a stop-motion character incrementally, what youre always holding onto is: Whats the feeling? Whats the emotion? Whats the character doing? When you know what youre going for, thats when itll flow, and the eyes will widen at the right moment and all of that.

Chris Sadler (lead animator): I was the character leader on Victor, the bad guy. A lot of what we do is very much influenced by the dialogue, while the design and shape of the character often denotes what hes going to be. Victor is a very portly character, but with long skinny arms and legs, which means hes very gesticulatory, almost in a John Cleese way. His head was so tall that we had to keep it quite stiff; if it had moved around too much, that would have translated too much motion to the top of the head and it would have been all over the place. We gave him this sort of stiff-backed, strutting movement. His neck is very set into his body, so if he moved his head, he would generally move his whole shoulders, which gave him an air of superiority.

We had a problem a few months into production, because we drifted into Victor being too much of a fool, rather than a real serious villain. Id grown so used to him being a pompous idiot that he was getting too soft. It wasnt until we got to doing some of the things in the scene in the woods, when he gets pretty nasty; that he started to come back into the way Steve Box had imagined him.

Key animator Ian Whitlock goes through the painstaking work of animating the characters. Many of the animators were split up with a main unit doing wides, and then two or three sub-units with the same set on a smaller scale.

AO: Did you re-animate any of Victors scenes for this reason?

CS: No, but I wont say it wasnt thought of (laughs)! I think it comes down to the way hes portrayed in the script more than the way hes animated although if hes running round pointing a gun at someone, hes going to look threatening, unless I really screw up!

AO: Can you talk about the logistics of the production?

CS: We were filming on 33 miniature sets on the floor of Aardmans feature studio in the Aztec West industrial park in Bristol [where Aardman made Chicken Run]. You move around quite a lot depending on what sets and characters are available. Its part of the nature of making a stopframe feature that you cant stick to one character all the time. Most of my shots were of Victor, but I dont think theres a character in the film I didnt animate at one time, especially in crowd scenes where there wasnt enough room to get two animators on the set and one person had to do them all. A lot of people say the hardest thing for a male animator is to make a woman character look feminine enough, not like a man in drag. There was a female animator who did a lot of Lady Tottington toward the end, and she picked the character up very quickly, so there may be something in that

The character leads handle the scenes where their character is really important. For example, I did a lot of the scene where Victor is introduced at Tottington Hall, but even then I wasnt sole animator on him. There were some reverse angles, which were done by the animator in charge of Lady Tottington. Conversely, in the forest scene, I was sharing animation with the lead animator on the Were-Rabbit. First there was one main forest unit on which we did a lot of the wide shots. Later, we had a forest unit facing in one direction and the other in the reverse direction. In this way, Id do all the shots pointing back at Victor, while there was a reversed unit next door, which was handling what Victor was seeing in the scene.

A lot of the units were split that way a main unit doing wides, and then two or three sub-units with the same set on a smaller scale. In the first Tottington Hall scene, my set was pointing out across the garden it was very big and plain, with lots of grass, showing Lady Tottingtons POV. Next door was a much smaller reverse set just showing the doorway. And there were a couple of shots in the scene breaking out of that eyeline, when Lady Tottington walks down the steps, and that would be a different set again.

Dave Alex Riddett (director of photography): One thing thats developed through the Wallace & Gromit films are the famous chases. We havent changed the techniques very much, weve just got more elaborate, with bigger sets and more intricate ways of doing the sequences. A lot of the technique in Were-Rabbit amounts to having an enormously long background and literally moving it behind characters.

So in some of the climactic shots, Gromit is in a plane suspended over a set on a rig while a massive building is moved behind him on tracks, one frame at a time. Generally the backgrounds are real, shot in front of the camera, although weve done a lot of greenscreen for the plane shots and the fairground stuff, because our fairground sets were enormous. There were about four large fairground sets and at least half-a-dozen smaller areas of it, all Wallace and Gromit-sized. A lot of them had to be greenscreened because they would take up so much studio space, so we shot characters first and background plates afterwards. We spent the last few weeks of the film just shooting plates.

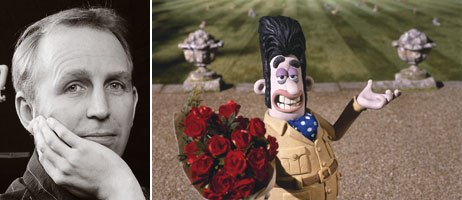

Early in production, Victor (right) was portrayed as a pompous fool, rather than a serious villain. As his actions became nastier, he finally became the character writer/director Steve Box had first imagined him.

AO: Tell us about how you created the look of the film.

DAR: People often say that the lighting on the Wallace & Gromit films is just like live action, but for us, weve never approached them any other way than lighting a real world. When we did Wrong Trousers, for example, we lit it as we would a live-action piece. There wasnt an intention of creating a style in those days, but a lot of it was from Nicks drawings and storyboards, which were very nicely composed. Theres always a coziness or homeliness about the way we light it, it has almost a retro feel. Its never stated, but its almost like its set in the 50s.

It becomes evident from Nicks drawings that hes influenced by certain films, so we were always looking at films like Brief Encounter (for the Wallace/Wendolene romance in A Close Shave). Obviously many sequences in Were-Rabbit are gothic horror, so we were looking at Universals The Wolf Man, and vintage James Whale films like The Invisible Man and The Bride of Frankenstein; also David Leans Great Expectations and Oliver Twist, and the musical Oliver! as well. Although, as I say, we light the films very much as live-action, for realism, this is very much a heightened realism, which those live-action films had.

Writer, director and producer Nick Park works on a miniature set. DP Dave Alex Riddett lit the film for live-action realism creating a retro 50s feel.

When we shot Chicken Run, we were over-precious about the detail of the characters, which were very slick and smoothed down. This time weve deliberately gone back a stage, because we realized that a lot of the charm lies in that handcrafted look. You can see that chunkiness about the textures, the fingerprints in there. In the past, we might have used the lighting and the post-production to smooth things out or cover up cracks, but now we revel in it. Unless its distracting, we allow it to be there, as part of the look.

AO: How about special effects?

DAR: Theres lots of fog in this film, and things like fire, water and fog are incredibly difficult in stop-motion because you cant single-frame them. We used some techniques that worked quite well but we also thought, why not try some live-action stuff with digital technology? So we filmed characters before a greenscreen, and then used a faster filmstock to film a live-action pass with the room filled with smoke. Then we married the two together in post-production. Londons Moving Picture Co. also computer-generated some fog effects in the foreground.

Theres a fair bit of other CG imagery in the film as well, like the rabbits floating round in Wallaces Bun-Vac. We were very cautious about it looking right, but the rabbits were perfect the limits of the CGI suited the look and they got the textures and the animation right. Im happier about working with this technology now. In the past, we were very purist about only shooting on film and having everything done in camera, but were more open-minded now.

AO: Finally, how do you feel about the film opening so close to Tim Burtons stop-motion The Corpse Bride?

LP: The last couple of years have been a good time to be a stop-motion animator. The sad thing is, obviously, now youve got a lot of people finishing production and looking for work. From that side, it would have been nicer if the films hadnt been simultaneous, and if people had been able to go off one movie and come onto the other, but it never works out how youd like it. But its great that stop-motion animators had the option to do either an absolutely top-flight puppet film, or Wallace & Gromit-style plasticine.

The first feature-length Wallace & Gromit outing was created by Aardman Animations with distribution through DreamWorks. Wallace & Gromit: Curse of the Were-Rabbit, directed by Nick Park and Steve Box, had a limited opening in the U.S. Oct. 5 with a wide release on Oct. 7. The Moving Picture Co. (MPC) completed more than 750 visual effects shots for Wallace & Gromit: Curse of the Were-Rabbit. The picture was color-graded by Max Horton in the MPC DI lab.

Its vege-mania in Wallace and Gromits neighborhood, and our two enterprising chums are cashing in with their humane pest-control outfit, Anti-Pesto. With only days to go before the annual Giant Vegetable Competition, business is booming, but Wallace & Gromit are finding out that running a humane pest control outfit has its drawbacks as their West Wallaby Street home fills to the brim with captive rabbits. Suddenly, a huge, mysterious, veg-ravaging beast begins attacking the towns sacred vegetable plots at night, and the competition hostess, Lady Tottington commissions Anti-Pesto to catch it and save the day.

Peter Lord, David Sproxton, Nick Park, Claire Jennings and Carla Shelley are producers on the film. Peter Sallis, who has voiced the role of Wallace in all of the shorts, reprises his role in the feature film. Academy Award-nominee Helena Bonham-Carter (The Wings of the Dov) and two-time Academy Award- nominee Ralph Fiennes (The English Patient, Schindlers List) are the voices of Lady Tottington and Victor, respectively.

Andrew Osmond is a freelance writer specializing in fantasy media and animation.