While many of us believe drawing is knowledge based, Jean Detheux explores how venturing beyond this "given" opens up an entire new realm of paradoxes, dilemmas and ultimately success.

It is not an exaggeration to state that drawing is basic to most forms of animation, just as drawing has traditionally been the foundation of painting (and sculpture, and so on) for a very long time.

Yet, from the point of view of drawing as an art form in its own right, drawing in animation is very weak, and above all, almost always lacks a dimension which is fundamental to art as a whole, the dimension of exploration, of discovery.

Most people "use" drawing as a means to a predetermined end; very few view (and live) drawing as a tool of exploration and discovery, a "flying carpet."

Sure, in the animation house, we have talented people who can rearrange the furniture in interesting ways once in a while, but basically, we are permanently stuck in the same old rooms, in the same old space (3D objects moving about in empty space).

Drawing is an activity that seems as basic as breathing and eating.

Yet, as basic as it may be, it is very seldom "natural," it is very seldom coming from our deeper "self," it is most often taught (and used) as an acquired language.

Most people believe that drawing is knowledge-based, that we have to learn how to draw in order to have some success with it.

If so, what is that drawing knowledge we (may) have to learn, what is it exactly that we can learn?

And what could "drawing without knowing" be, if anything at all?

Drawing the Immediately Perceived

Most people start to draw with the hope that their drawing will "look like" something they can visualize, be it as something they "see" around them in the (so called) "external world," or as something they imagine, "in their mind."

Either way, their ability to perceive and give form to those "visions" is what will inform their drawing.

At a very fundamental level, there is no qualitative difference between our "seeing" inwardly and outwardly. The distinction between "inner" and "outer," between "real" and "imagined" comes much later in the chronology of our consciousness.

The manner in which we constitute/organize those visions is what our drawing uncovers.

"Perception is constitutive," said Maurice Merleau-Ponty (Phenomenology of Perception ought to be required reading for all art students, and The Eye and the Mind could be a terrific introduction to his work, and to a deeper understanding of ours).

It seems to me that most people think that "the eye works like a camera and we all see the same thing," especially if the same people are totally indoctrinated into believing that there is an "objective" world, the same for everybody, and that the differences between our respective experiences are "merely" subjective.

In that frame of mind, drawing is a way by which we think we can (re)produce an image of reality as we believe it to look.

However, much of that "reality" isn't as "real" as most would think, it is above all based on expectations, expectations rooted in culture, shaped by language.

We can hardly see some "thing" if we do not have a name for it, a label, with which to isolate it, to differentiate it from the infinity of available stimuli, from the infinity of potential readings available in any and all situations (the "here and now" as a door to infinity, the living present as "infinite manifold," as Husserl called it).

Things Are Not As They Seem

When still a student at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts de Liège (Belgium), I tried my best to follow the methods we were taught, much of which was based on an "explanation" of the appearance of "reality," an explanation that was rooted in the belief that the world consisted of solid objects existing in empty space.

The notion that the objects retained their identity and were always easily distinguishable from their surroundings was one that made it fairly easy at first to draw, but progressively this notion started to be challenged by the evidence of my own experience ("things" were not always behaving as they were expected to, according to that "objective world" theory).

Most painters whom we, as students, were encouraged to study, seemed to function with a great deal of ease within the confines of that system of belief, a system with which I, like a few colleagues, felt more and more uncomfortable.

Yet, and this is very significant, the painters that were identified as the greatest (Rembrandt, Vélasquez, Vermeer, Chardin, Cézanne, just to name a few) were not always respecting the "norms" of that theory ("solid objects existing in empty space").

In fact, it became increasingly evident that the more "potent" the paintings, the more they seemed to not respect the "rules."

Trying to emulate those successful paintings by applying a "style" was mildly successful, but always felt "off," and was obviously not the way to go, nor seemed to be the way "they" (the painters I was studying) had gone.

No matter how much I twisted the possibilities available in the "solid object in empty space" world view, I always came out with works that were very short of what those painters had obviously made available, and that they made available in a very consistent manner.

Either I trusted "my" perception as guided by my naive faith in this "objective world," and always ended up with drawings and paintings that were very trite, or I manipulated those images that were made possible by my reliance on the "objective-world" model and came up with works that may have seemed more "interesting," but which were, to me, lies, fabrications, and very much at odds with what got me to study art in the first place (call it a search for truth, for meaning, for "self," the Holy Grail, whatever).

Surely, based on the impact of my experience of some of the better Rembrandts, and such, there had to be more to Art than that!

There had to be (an)other way(s).

Another Point of View

Invariably, when working "from the visible," I would have moments during which none of what I was seeing made (habitual) sense, and during which my (traditional) way of drawing was terribly inadequate.

This seemed to happen more and more frequently, the more I tried to "capture" the visible, the more I would fail, or, if "successful," the more disappointed I would be with the results.

I was becoming very confused, and unfortunately I did not (yet) trust that confusion.

That's when I met a great teacher, Joseph Louis, who held one of the keys for which I was looking.

Joseph deeply believed that our perception held keys to Art, and that what we needed to do was to become able to "see the visible in terms of abstraction" ("voir le visible en termes d'abstrait").

With his competent help, I (and quite a few other students) became more able to focus on that which did not behave according to the "solid objects in empty space" model, and to follow all the openings ("passages") I was exposed to all the time but kept on editing out because they did not conform to the societal model.

Very quickly, this approach made us realize that we had a lot more in common with the likes of Rembrandt, Vermeer and so many others than we originally suspected, and that the depth of their work was not based on a greater theoretical knowledge and skills (like "exceptional talent" or "super tricks") but instead was rooted in a greater connection with their own particular perception.

The realization that Art was not at the end of knowledge forever changed our relation to Art and, of course, to school.

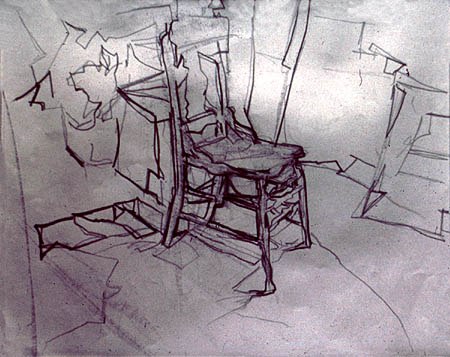

Joseph Louis introduced us to the work of Alberto Giacometti, and that is when I realized that the kind of "failure to draw/paint what I saw" was not my problem alone; I could see in Giacometti's works the very same experiences, though with a huge difference: unlike me, he was accepting that constant failure, and was in effect riding it the way one rides a wave.

Camus' "the failure shall be the measure of success" came to mean something to me finally!

We also could sense that those deeper modes of perception were available to us as well, though they would require much work (and luck?) if we were to ever be connected with them in a meaningful way.

This is a point at which a choice needs to be made, where in fact a choice *is* being made, by each and every one of us, each and every time we work: "Rembrandt or South Park?"

Much of what I dislike in habitual animation is born in and from a world that remains very short of this search, it almost exclusively wallows in what is done when this search for "truth" is kept silent, when the choice I talk about is made, but made in the same manner one sweeps dirt under the carpet.

Embracing this search is no guarantee of success, far from it, this opens doors to paradoxes and dilemmas that can be, and often are, very painful.

I recall a comment Picasso made when he put an end to the work he did with Braque. He had been painting with Braque for a couple of years, years during which he , in my opinion, painted his very best work ever. He said: "To continue to paint like that, I would have had to live like a monk."

I don't think he was talking about celibacy only (if at all); I think he was talking about a form of concentration he was unable to sustain, a concentration on a basic unresolved dilemma, which -- if unresolved -- very few people can live with permanently.

One way of putting this dilemma into words is this: Is meaning found or created?

If found, it means I am nothing ("it" independently exists outside of me).

If created, it means that I am utterly alone (alone because this "Meaning" cannot be experienced -- as such -- by others, as it belongs to their "external reality").

Merleau-Ponty points to this dilemma/paradox this way: "We derive meaning from our experience while simultaneously projecting meaning into it," (in effect pointing to the dilemma/paradox with which we seem to be living at every breath).

The tension this type of dilemma generates is precisely the wave Giacometti was riding, it is precisely the type of tension I was determined to sustain, to investigate.

A Different Approach

Going back to working "from the visible" armed with this new "understanding," I no longer tried to force the visible to conform to my habitual differentiation (as between "figure and ground"), but instead, I switched my attention from, "What is that?" to "How does 'it' appear?" (And it no longer mattered if that "it" remained undefined, unlabeled, in fact, the longer that undefined quality remained so, the better the work would become, though this would often be recognized long after the fact.)

Progressively, the focusing on "the appearing as it appears" yielded drawings and paintings that were very different from my previous work, and yet much closer to the work of artists with whom I was most impressed.

Imagine that: I was getting closer to my heroes and this, not by emulating or plagiarizing their work, but by paying more attention to my most personal experience!

Indeed, the exhilarating part of this was that the similarities between their work and mine did not come from emulation, not at all, but came instead from a deeper connection with my own experience of "the real."

It is possible to break the stronghold societal models have on our experience of the visible, but to do so requires a serious effort, an effort that is turned "inward" as it were, quite different from much of what most of us are used to doing.

For example, seeing "this" means not seeing "that."

This means that most of our visible world -- as a context -- is held in place by our constant projection in the experience of the "here and now," all that we remember having seen, and that we anticipate seeing.

In that sense, the "naive" (not pejorative) experience of the "here and now" is loaded with recollection, and anticipation.

If we did not do that "naturally," we would not be able to read a sentence, or hear a musical phrase, or make sense of a representational drawing.

Animation itself relies on this naive recollection/expectation in order to appear as a continuous "meaningful" flow.

In fact, if we did not have this loaded "living present," we would not be able to make habitual sense of the world in which we live.

And yet, this is reality as we constitute it, it is not reality as it appears to us prior to our being actively engaged in our sense making projects.

This projecting into what we see of the parts we do not see but assume are there is called "adumbration," and we constantly "enrich" our experience of the visible world with that adumbration (it's like looking at the moon and giving it substance by projecting into the experience the faith we have in the existence of the parts of the moon that we cannot see).

The problem with (naive) adumbrating is that we can only project into the experience that which we already "know!"

In other words, living and seeing that way condemns us to see the world not as it appears (as it is constantly appearing), it condemns us to see "it" strictly as we imagine it to be, our imagination being formed by our culture, by our language, by our expectations. (Other cultures, other languages, give birth to different expectations, to other habitual visible realities.)

Undoing The Done

Surely, there have got to be ways by which we can "undo" the control that our culture, our language, have on our experience, ways by which we can, at least temporarily, put aside these controls, shelve them, "bracket" them, and see "the appearing as it appears."

We will be looking at some of those ways in greater detail in the next article(s), but here are a few things that may interest those who want to explore this a bit further: physiologically, unlike film, our vision is not based on an even field, with a capacity to receive external stimuli with the same accuracy evenly distributed on the retina.

Far from it!

Our peripheral vision is very different from our central vision.

In a nutshell, our field of vision is mostly constituted by light-sensitive rods, rods that are connected in groups to nerves that carry the signal to the brain. Only a relatively small area on our retina is equipped with cones, cones that are connected individually to nerves and able to convey a far greater amount of detail (and colour) to the brain.

There's a lot more to this: for example, the rods do not respond to/transmit colour, while the cones do. The rods are connected in groups to nerves and can respond to/transmit movement far more than the cones can, but they cannot provide much image "resolution;" only the cones can.

Most people are very amazed when, through very simple experiments, they come to realize how tiny our central area of vision is (the only one that provides for sharp image differentiation and colour) in the context of our whole field of vision.

I am not positing here that all there is to vision is based on physiology, but I am finding this to be a good place to start, and will try to show in the next article(s) how much the basic "center-periphery" (dynamic) structure also applies to "higher" functions.

To start paying attention to the enormous qualitative differences between our central and peripheral vision can be a great place from which to begin looking into "seeing without knowing," a gentle beginning that is nevertheless one reliable place from which to try to see beyond/through the walls of perception (no doors yet!;-) by which we allow ourselves to be trapped so readily.

To try to implement -- in one's drawing -- the qualitative differences one notices between central and peripheral vision is the beginning of a journey that could yield many frustrations, and many discoveries.

It is fair for me to remind the reader of what I said in "Part 1 -- Animation, Prozac or Kyosaku?": "This inherent style is the intrinsic 'flavor' of one's continuous and inevitable failure to succeed at capturing reality."

What I am proposing here does not lead to greater "control," it may make it possible to connect with another mode of experience or more precisely, with a greater awareness of how our experience is taking place.

The next article will look at this in depth, and talk about how it so often is the case that, in our better work, we draw with, for example, charcoal in hand on a paper placed before us, but almost invariably, the better (the "real?") work is born as if it had been done behind our back by a charcoal that is attached to our elbow.

How is it that, so often, our better work is done without our being aware of its genesis?

How is it that, so very often, "our" better work is done as if it had been made by an "other?"

How does "the other" come into play when I am trying to draw how "I" see?

Those are the questions we will spend time with in part #4.

One reminder: if drawing is basic to animation, perception is what drives drawing. . .

Jean Detheux is an artist who, after several decades of dedicated work with natural media, had to switch to digital art due to sudden severe allergies to paint fumes. He is now working on ways to create digital 2D animations that are a continuation of his natural media work. He has been teaching art in Canada and the U.S., and has works in many public and private galleries.