Read how the VFX powerhouse embraced imperfection for its first animated feature.

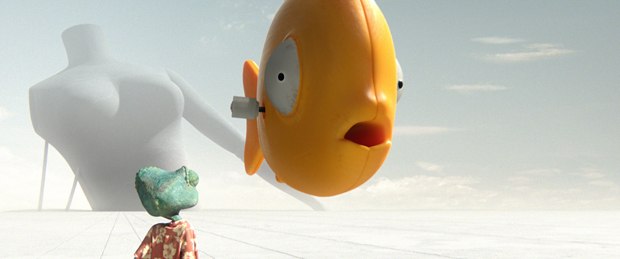

As Hal Hickel tells it, animators at Industrial Light & Magic have been chomping at the bit to do an animated feature for quite a while. Well, they got their wish with Rango, the strange and funny film directed by Gore Verbinski (the Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy) that's a mash-up of spaghetti westerns and Chinatown, opening today from Paramount Pictures. The eponymous character (Johnny Depp riffing on Don Knotts and Jack Palance) is a chameleon on an existential journey, who becomes sheriff of Dirt, a desert town suffering from total dehydration.

And Dirt is the operative word.

"As Gore started to download his vision, we realized it was going to be perfectly suited to ILM," admits Hickel, ILM's animation director. "And the reason for that was it boils down to one thing: we've been making pictures dirty. To begin with, we knew it was going to be a unique project coming from Gore. It was not going to be group think. It was going to be a very small, creative nucleus of Gore, [production designer] Crash McCreery and [artist] Jim Byrkit. And the rest of us surrounded that. It was a personal filmmaking experience.

"What he wanted was something very different from the neat and tidy and colorful mainstream feature animation that we've become accustomed to [with computer animation]. He wanted something dirty, grimy, dusty, fuzzy. And it wasn't just an exercise in weirdness for weirdness sake. It was a real intention stemming from a love of the Sergio Leone westerns and the actors always looking so gritty and sweaty. And also it was just toward the goal of crafting a well-intentioned, deliberate, tactile world that you can believe in: something not photo-real but photo-surreal. So this concept of Dirt, which was our working title at ILM, was also the name of the town and how it should feel."

But it's not easy beating perfection out of computers. Still, ILM worked wonders in keyframing a very, parched, tactile world peopled with a bizarre gallery of desert creatures.

Of course, it helped free up the actors as well as the animators with Verbinski working in live-action mode, shooting the actors together on stage in an orchestrated chaos of performance, and using ILM's virtual set technology, enabling him to walk around the stage with a viewfinder and compose shots and record both storyboard frames as well as actual camera moves as he saw fit. Often times this either built upon moves done by the layout team or became a starting point for the layering of their work.

The first thing you notice, of course, is the eyes. They're not only very large but have some unique characteristics. "There was a risk with such large, ugly eyes," Hickel suggests. "We thought there was a real opportunity here and we looked at pictures of chameleons. There is really something soulful and cool about them that was a tradeoff for battling with this weird design. There's a lot of detail in the whites: all kinds of layers and styrations and pearlescence that pull you in without being too busy or unreadable. Not only that, but the eyes have no real cornea to bend light as it hits the iris and changes, so ILM set back the pupil and the iris from the outer surface.

"As the angle to the eye changes, using Buford [the desert toad] as an example, you'll see the magnification," Hickel continues. "It's part of giving the characters some interest and depth beyond the simple graphic representation of the eye."

Creating Dirt and the other desert environments was just as challenging, according to Tim Alexander, ILM's visual effects supervisor. "Environments had to carry the story as well," he says. "We had to step up the detail in the environments: the grit, the grime, the atmospherics. The town of Dirt has 36 buildings. We had to make it feel like they're living in dirt and be just as detailed as we were with the characters."

For ILM, that meant rethinking layout. "Layout was a different animal," Hickel admits. "We got them thinking more about sequences rather than shots. But there was just a whole bunch of complexity that we underestimated. You've got all these things you're building for the film, right? The town and every bar stool and shot glass and cactus and rock. And all those objects have to be fed into layout and set dressed. It's like the nexus of all these departments that are working and feeding into it, and getting that system right was a challenge. You'd go from layout to animation and sometimes maybe the highly detailed version of a building isn't ready yet, so they'd build us a proxy version for the animator to work with, and would have to get swapped out later with the full version. But the whole system had to work where that could get swapped out and nothing breaks.

For the animators used to working on VFX films, it was a matter of now creating something out of nothing, even though they had the performance footage as reference as well as their own reference they created for themselves. "They're used to reacting to the live-action footage as a framework," Hickel suggests. "But here it was closer to a blank slate. It's funny, they [couldn't wait to get in there] and act and not worry so much about having to integrate with the live action. But as soon as they got in there, they realized how much work was involved."

It was the same with the lighters, too, because they suddenly had so many creative options at their disposal. To help them along, ILM developed some new tools, especially for earlier and more accurate QC'ing before lighting among the various departments. The Previewer enabled the lighting TDs to interactively check where the light's going to fall, and the Sequencer allowed them to load some or all of the shots in a sequence in one file for easier lighting and relighting. For instance, a campfire sequence comprised of 56 shots was lit by two artists.

In addition, ILM created a new team right before lighting called preflight: this group took all the shots and rendered frames to make sure the shot was operating correctly.

Meanwhile, the flying bat chase (accompanied by The Ride of Valkyries) was the most difficult action sequence, given the number of rodents and complexity of the canyon. Dan Wheaton, lead environment TD, built the canyon in sections so ILM could keep adding to it and changing shape as they went down the canyon.

In terms of characters, Tortoise John, the mayor (voiced by Ned Beatty), was especially challenging, but, fortunately, the similarity to John Huston's Noah Cross from Chinatown proved instructive. There was just something about him that wasn't working. "His shirt looked a little rumpled and he didn't look like a man of power," Hickel explains, "and so we went back and looked at that scene in Chinatown where Noah Cross is sitting and eating lunch, and we noticed that his shirt had this stitching on it that made it look rich, so that got added and we firmed up the modeling of his collar so that it had a bit more starch. We cleaned him up and made him up a little more impressive."

An even more recognizable figure, known simply as The Spirit of the West (voiced by Tim Olyphant), proved even more challenging. "We knew we wanted to stylize him and so then it was really an art direction journey for quite a while," Hickel continues. "I think Aaron McBride did a lot of the heavy lifting. Aaron even sculpted 3D forms in the computer. And then it was just like anything else: building the model and turntabling it and working iteration after iteration. At some point, you just wanted to get him in the shots and light him and make some final changes. There is such a cult around him and everyone wanted to get it right."

Bill Desowitz is senior editor of AWN & VFXWorld.