In the latest excerpt from The Advanced Art of Stop-Motion Animation, Ken A. Priebe talks with Pete Kozachik, ASC.

Pete Kozachik has worked in the film industry for over 30 years as an animator, visual effects artist, and cinematographer. He was the director of photography and visual effects supervisor on The Nightmare Before Christmas, James and the Giant Peach, Corpse Bride, and Coraline. On the latter two films, he was instrumental in adapting the technology behind the first uses of digital SLR cameras and stereoscopic photography for stop-motion. He also grew up in Michigan, like me, so for this reason and so much more, I’m glad to have his contribution to this book.

KEN: Can you tell me about your background and how you got started in stop-motion?

PETE: As a kid I had seen both King Kong and Seventh Voyage of Sinbad within a few weeks of each other, and they got completely seared into my cerebrum (or wherever those things get seared). It wasn’t clear to me at the time what I was looking at, but it affected me so much. I remember sitting with my mom in the theater at age 7, watching Sinbad, and out of concern that it might have been too scary for me, she leaned over and suggested the creatures on screen might have been giant robots. So for the next few years I had it in my mind that the U.S. government had a secret fleet of giant robots with rubber suits on, and let Hollywood use them.

Then at some point I saw a photograph of Ray Harryhausen posing next to his Cyclops and Dragon puppets, and it all became clear. I realized those figures weren’t as big as I thought they were, so it was something I felt I could do. There wasn’t any information out there about how Ray’s films were made, but I managed to experiment enough to start making my own stop-motion films. By the time I was in high school, we had moved to Tucson, Arizona, and I showed some of my films around town. This got me some jobs working at various TV stations, mostly shooting and working with some industrial filmmakers. After graduation from University of Arizona, I put my name out as an animator, picked up a few years of work on commercials and industrial films, made a reel, and then headed to Hollywood in the late ’70s.

I got lucky enough to start working for Gene Warren, and later with Phil Kellison, both having backgrounds in stop-motion. Phil was a director at Coast Special Effects and became one of my early mentors in the craft. I ended up working there for several years, and it was such a valuable learning experience. I had it in mind to watch the animators work, but stop-motion animators are actually not that interesting to watch, because they move very slowly and it’s all just going on in their heads. But I remember one of my first nights there, cleaning up after someone’s shoot, and opening up a drawer with a row of Pillsbury Dough Boy heads. I was so totally transfixed by that, because these heads seemed too precious to even look at, and I’ve never really lost that fascination.

KEN: What kinds of projects did you work on there?

PETE: Coast Effects made most of their money on commercials, but they would also bring in low-budget features to keep Phil Kellison happy, since he liked to work on those. We would use stop-motion whenever we could, even if it was just a spaceship, or whatever. It was a small part of a larger company, consisting of only a dozen or so of us, so we all did a little bit of everything. If a star animator like Laine Liska was too busy, sometimes I would animate something, and they would just tell the client that Laine did it. At one point I had brought a motorized spaceship prop I built to the set, and the cinematographer suggested that since I had built it, I should shoot it. This led to me transitioning from animation to more work in camera, motion control, and photography. After a few years at Coast, I answered an ad for a cameraman at Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) and moved up to the Bay Area to work on feature films.

KEN: How did you end up getting involved with The Nightmare Before Christmas?

PETE: I had worked with Phil Tippett on Willow while at ILM, and ended up working for him exclusively at his own studio for the last two Robocop films. I essentially brought motion control to Tippett Studio and spent some serious time there, at a point when they were starting to gain more momentum. Phil Tippet’s studio worked organically, a lot like Coast. That’s not too surprising, as he was an earlier alum from Coast. Henry Selick had been renting space there for his short film Slow Bob in the Lower Dimensions, which we shot as a pilot for MTV. Around that time, Tim Burton asked Henry to direct Nightmare, and based on the strength of Slow Bob, approved the idea of bringing me on as director of photography.

At exactly the same time across the studio, Phil Tippett was gearing up to shoot stop-mo dinosaurs on Jurassic Park. He made a tempting case for me to work on JP, doing this really cool stuff with dinosaurs, and I said ‘yeah I know, but Henry’s got this thing going where it’s not just effects, it’s a whole movie.’ So we went back and forth on it, but I ended up going with Nightmare because I felt it was a great opportunity to tell an entire story with stop-motion, which I had never done before. It is a major commitment to jump onto a show like that, because you are basically throwing about 3% of your life into it, so it had better be good. It becomes a much bigger part of your life than making shots for a single sequence.

KEN: On a stop-motion film, how is the decision typically made whether to do effects practically on set or in camera, versus doing it later in post-production?

PETE: I’d like to say it comes down to personal taste. When Henry Selick and I work together, the personal taste would usually be to do as many effects in camera as possible, but there are practicalities to consider too. Back when we were shooting on film, and there was no such thing as digital compositing; you got better quality if you did everything in camera, but that doesn’t really hold water anymore. Composites used to be hugely expensive, and now they’re not. It used to be worth risking a re-shoot as opposed to having a grainy film composite, or an “optical” as it was called then. On a film like Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, shots would be done in camera, and spending months of laying images onto the same negative.

These days there is a lot more green-screen shooting going on, which I think is good, because then the animators can focus exclusively on their performance, rather than all the steps of multiple passes through the camera. Directors have a lot more freedom now too, so rather than being told that elements have to be shot with all sorts of restrictions, they can call for more ambitious shot designs, and darn near anything can be lined up digitally into a seamless composite.

On Nightmare, we did our best to get a lot of effects in camera, so we used a lot of front and rear projection directly on set, in order to add real flames to the torches, and things like that. My personal take is that stop-motion should have some degree of real-world physics in it. Elements like water splashes, smoke, and fire are from the same world that the puppets are, and I feel it can be a richer experience for the audience using elements that are shot in real life. I also still respect films that go with the cute approach of using cotton or stylized cartoon animation for smoke, and we’ve done a few things like that in our films too. I remember enjoying that kind of approach as a kid, watching things like Gumby.

KEN: Is there any particular shot you’ve worked on that stands out, in terms of capturing the magic of stop-motion with brilliant effects work?

PETE: There is a sequence with the Corpse Bride, starting with her coming out of the ground, all the way to when she and Victor are on the bridge surrounded by a flock of crows. There are a lot of shots in that sequence with complex composites (comps) in them, and some of the most painstaking animation ever done, in particular on her clothing. There were a couple of shots where we had to throw in the towel and use computer animation on her veil. It was still supposed to look like stop-motion, and luckily the animators pulled it off. Some of the shots don’t even look like they needed post work to begin with, but in some instances we had to add extra background just because we couldn’t practically fit it into the stage. Overall I love everything about that sequence, and when I signed on to the movie, that scene was the one I was thinking about. I was envisioning an image that might have been in old horror comics, part spooky, part sexy, pretty much everything that parents didn’t want us to spend our allowance on.

KEN: What were the challenges you faced using digital SLR cameras for the first time on Corpse Bride?

PETE: I think the biggest challenge was taking this new technology that wasn’t really designed for that purpose, and very quickly adapting it to professional work. We had challenges with everything, even including stringing the images together and looking at them.

There are all kinds of agreed-on standards to the century-old film technology, including how sensitive it is, in terms of its ISO rating. We got into a pickle early on in Corpse Bride, shooting test images with these cameras. When we viewed the images on stage in Photoshop, it would show us a better image than what we were capturing. So unbeknownst to us for several shots in the movie, we were drastically underexposing them and had to ask the visual effects crew to tweak them into usable shots. To establish a safe standard, we had to pretend we were shooting on relatively slow film and not plan on enhancing it in post. This made it feel like we were going backwards, but ultimately it made life a whole lot sweeter in the color grade, since the shots did cut together without much tweaking.

Another problem was dust falling on the unprotected image sensor, which wouldn’t be there when we started, but each time the mirror flipped, chances were that some dust mote would get in there to drift down on the sensor.

So there were minor issues like that, but on the other hand, the SLRs allowed for things that were unheard of back when we used those 30-pound Mitchell cameras. With those, you really had to consider how much the camera weighed, how you were going to support it, and how the animator would get their head around it. Suddenly, when the cameras were tiny, we were more on par with what live-action could do. If live-action film had to mimic how stop-motion used to be shot, the camera would be the size of a Volkswagen.

KEN: So what kinds of things should a stop-motion filmmaker shooting with their own SLR camera keep in mind, or watch out for?

PETE: There are a few things which now seem rather obvious. First of all, turn off everything that is automatic: iris, exposure, focus, ISO, white balance, everything, and dumb the camera down to the point where you are manually in control. But much more important than the technical stuff, is that people seem to be losing time waiting for the ultimate perfect camera to show up, and it hasn’t happened yet. The closest thing right now is probably the Canon 5D, which will be valuable for a few years until something better comes along. There is a lot of hot air wasted on the minutia of how much better photography can get, or how much more resolution you need. As filmmakers, we should help the audience focus on the story, the drama, and the characters. That’s what they buy tickets for. If you’re only sitting there admiring the image sharpness, then somebody didn’t do their job. So my most heartfelt advice is simply to get off the Internet and start shooting with what you’ve got.

KEN: What would you say are the differences and similarities between shooting for live-action and shooting for stop-motion?

PETE: The thing we have been trying to do, with all of the crews I have worked with, is to emulate the same film language and techniques as are used in live-action. Most of the time it can be done, in terms of lighting, composition, lens choices, color, contrast, camera movement, and things like that.

On Nightmare we were first experimenting with camera techniques that were fairly well accepted in the live-action world. As we experimented, we often wondered if it was going to end up being a bad fit. As an example, the character of Sally (with no disrespect to the puppet builders) is essentially a crude representation of a woman. There are visible signs like seams, brushstrokes, or other imperfections that make it obvious to the audience she is only a few inches tall. So the question became, can we take this puppet and give it the 1930s/40s glamour treatment with the lighting and camera, or will it just look ridiculous and ghoulish? Well, to our surprise, it worked! Through using diffusion filters and other techniques, there were many shots in the film where we treated Sally the same way we would have treated the romantic leads in Hollywood’s golden age.

The differences between live-action and stop-motion lie in the disciplines you have to apply to setting up a shot. In live-action it can be OK to rig setups somewhat precariously, with the understanding that they only need to last as long as the take, so there is a certain amount of serendipity involved. In stop-motion, you need to consider the long haul when setting up a shot. The demands are greater these days, and nobody finishes a shot in one day anymore. A shot may take several days or even weeks, so there can’t be any opportunity for things to slowly change over the passage of time, like a light bulb slowly getting dimmer, a set warping from the humidity, or a camera slowly losing its position. It’s the same with light leaks. Back when we shot on film, even if we had a good camera (and usually we didn’t), it was wise to bag the whole camera so that some little unseen crack didn’t slowly leak in light and fog each frame.

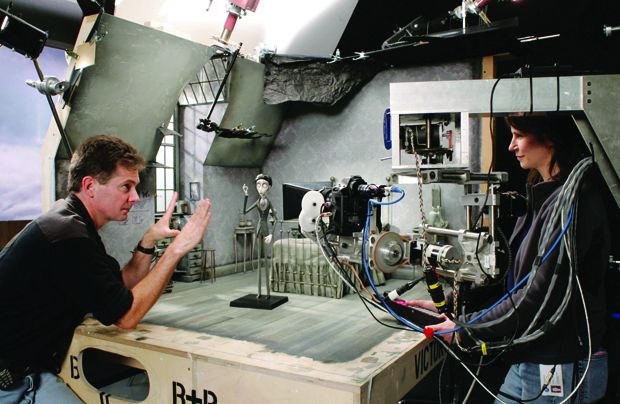

The other thing to think about is access for the animator. They will be walking back and forth several hundred times during a shot, so you don’t want to have too many c-stands or cables getting in their way. Chances are, if there’s an obstacle, they will step on it or bump it, and it’s really hard to get things back to where they were. A lot of visual effects work in stop-motion has to deal with getting elements into a shot that couldn’t be there while the animator was at work. When possible, devices like trap doors or walls that can be pulled apart and back together between frames can be designed into the set instead.

Another unique element of stop-motion is that in order to get shots out in a timely manner, we need multiple crews. On Coraline I had about 30 people who were broken down into about 8 or 9 different units. They were primarily cameramen, electricians, and assistants, plus some tech support people, so there is a lot of parallel processing going on. We had about 40 sets all going at the same time, simply because we had to. You couldn’t live long enough to finish that show with just one crew.

So it’s also really important that every single crew person goes to dailies, not just the lead crew members. Everyone needs to see what others are doing, so the shots cut together properly. Part of my job as DP was to make sure communication was indeed happening between sets, because it takes effort to walk 200 feet through a maze of sets to check out a set on the other side of the building. There were some electronic aids there, used for sending still frames to other people’s computers, but direct communication is still vital.

KEN: What are your thoughts on the future potential for this new stereoscopic technology that was used on Coraline, and 3D movies in general?

PETE: I’d like to see 3D used in the same way that music, color, and sound have always been used in film. It needs to get to the point (and I think we are getting close now) where it is no longer the main reason for going to the show. I can remember back to the point where almost half of the movies I went to as a kid were black-and-white, and we would sometimes choose which movie to see based on whether or not it was in color. That’s ridiculous, of course, and I would say the same for 3D. But there is room for everybody, and hopefully we will also start to see films where everyone agrees that 3D won’t add much to it. Then we can spend our resources on more time on set, better filmmaking, and things like that. 3D is a great technique, and I’m glad that Coraline was made that way, as it makes it more fun to watch. But I’ve talked to people who didn’t see it in 3D, and they liked it too.

KEN: What are your thoughts on the future potential of stop-motion as an art form?

PETE: Stop-motion has done a lot in the near century it’s been in use, mostly on the fringe. It started as a visual effect technique and then it got blown away in 1993 with Jurassic Park. All the same, I would still love to see or work on a classic Harryhausen-style monster movie in stop-motion, so we’ll see what happens. Stop-motion’s best future is most likely in the niche it’s forming into now, which is stylized imagery that has something different going on than CG animation. Luckily, most people know what they’re looking at now, thanks to MTV and the glut of media and information we now have. Because of that, stop motion can be appreciated for itself.

Ken A. Priebe has a BFA from University of Michigan and a classical animation certificate from Vancouver Institute of Media Arts (VanArts). He teaches stop-motion animation courses at VanArts and the Academy of Art University Cybercampus and has worked as a 2D animator on several games and short films for Thunderbean Animation, Bigfott Studios, and his own independent projects. Ken has participated as a speaker and volunteer for the Vancouver ACM SIGGRAPH Chapter and is founder of the Breath of Life Animation Festival, an annual outreach event of animation workshops for children and their families. He is also a filmmaker, writer, puppeteer, animation historian, and author of the book The Art of Stop-Motion Animation. Ken lives near Vancouver, BC, with his graphic-artist wife Janet and their two children, Ariel and Xander.