Joe Strike looks into the new renaissance in animated shorts to find out the trends and how revenue opportunities are growing.

Shorts are alive and well, and finding new ways to reach audiences. Patrick Smith has created six short films since 2001, including his latest, Puppet. © . Patrick Smith.

Once upon a time and apart from the occasional animated feature, "cartoons" meant short cartoons -- Hollywood creations starring now legendary characters who filled out double bills at a studio-owned chain theater.

The studio and theatrical distribution system that supported this golden era may be long gone, but animated TV series starring popular characters in 11-minute adventures are happily carrying on the Hollywood tradition. Meanwhile, shorts are thriving outside of TV as well. They've adapted to new technology and have found new ways to reach audiences. Shorts cartoons serve a different purpose these days -- several different purposes as a matter of fact.

Making money isn't one of them, or at least not near the top of the list if you're an independent animator. "My students get tired of hearing me tell them there's no money [to be made] in independent shorts," says New York animator and instructor Fran Krause. Cartoons are a labor of love for this crowd; as with any artist, it's a form of self-expression that can't be denied, and earning a living is a secondary consideration. "For the most part I make a living doing commercial work," Krause adds, "but it's hard to see your creative output watered down by marketing decisions. When you make your own films, you don't have to run your work past committees or advertising clients -- you can make a decision in three seconds."

Krause's for-hire work has shown up on the Discovery Channel, Nickelodeon and Saturday Night Live, but independent cartoons (Moonraker and Birdhouse, both made in 2004) are a way of recharging his creative batteries. Balancing freelance assignments and personal projects can be tricky, however. "I used to make my own films during the two or three months I'd be out of work over the course of a year, but for the last couple of years I've been employed pretty much full time. I have to resort to making 30 second films with my brother Will." Krause is referring to films like Robot Dance Party, which actually runs 55 seconds and was made in a mere three days for a New York ASIFA screening. In the meantime, he's keeping his fingers crossed that Cartoon Network will greenlight a series he's developing for them.

With his own production company (Blend Films), a slew of directing credits to his name (including MTV's Daria and numerous TV commercials) and a side career as a painter, one wonders where Patrick Smith finds the time to make short cartoons for himself. Yet he's managed to create six personal films since 2001 featuring chisel-featured characters trapped in vividly realized, allegorical situations. (The sixth film, Masks, is due out in 2007.)

Smith says that originally, his independent films were "100% subsidized" by his commercial work, but now they're beginning to pay their own way. "Funding is starting come in from different sources. I'm getting more European TV deals from channels in different countries. For example, I just signed a contract for distribution in Germany for I think Euros1,000. That's not a lot, but there might be 10 or 12 such contracts in Europe alone. That begins to add up."

Bill Plympton's Oscar nomination for Guard Dog increased the short's earning potential. "It had great distribution," he points out. "It ran in over 100 theaters." © 2004 Bill Plympton.

Smith looks at his independent films as a way to keep his creative edge sharp and keep his name and work in the minds of the New York advertising community. The day after a recent invite-only showing of Puppet, his most recent short at a Greenwich Village screening room, Smith estimated that "half the people there were from the advertising world. It's relative -- a lot of agencies want to hire the independent people. Last night wasn't to show off the last spots I'd directed; it was about independent film. It's a little more legitimate and I think people appreciate that."

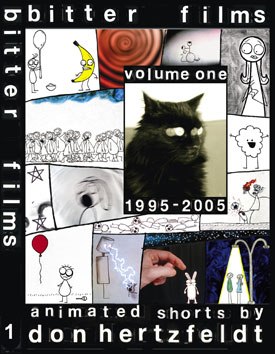

Krause points to superstar independent animator Bill Plympton as one of a tiny handful of people actually earning a living from their animated shorts. Whether not that's actually the case is between Plympton and his accountant. However, with his instantly recognizable style, Plympton (like Smith) enjoys a steady stream of advertising work to accompany his personal films, and is particularly well versed when it comes to marketing his work. Both men point to long-running venues like the Spike & Mike Festival and The Animation Show, compilations that run in theaters and appear on DVD. "The Animation Show is my favorite," says Plympton. "Don Hertzfeldt and Mike Judge [the compilation's organizers] have a lot of energy and compassion. They really believe in their films and work hard to get good press and good audiences. They pay a lot more money, too -- multiple times what Spike pays"

Plympton adds that an Oscar nomination (like the one he received for 2004's Guard Dog) increases a short's earning potential, particularly with new outlets like Magnolia Pictures' compilation of Oscar-nominated cartoon and live-action shorts. "It had great distribution," he points out. "It ran in over 100 theaters.

"There's a sort of mythology that it's impossible to make money on short films. I, and a bunch of others, including Don Hertzfeldt, have proven that's not true. You can make money if you're smart, keep your budgets low and your films short and funny. Short, cheap and funny -- kind of the way I like my women."

There's a myth that money can't be made on short films. Plympton and Don Hertzfeld are among those to prove the fallacy wrong. Hertzfeld just released a DVD compiled from a decade's worth of work.

While not an appreciable revenue generator, an independent animator's cartoon can still make an occasional, ego-boosting solo appearance in front of a feature film's theatrical run. "It happens all the time," says Smith nonchalantly. "You'll get a $100 rental fee here or there -- there isn't a heck of a lot of money involved. Sometimes I'll make an arrangement with the owner of a theater that hosted a film festival to screen one of my films. It's not the heavy mass distribution you're looking for, but it's cool to have your cartoon before a feature."

It's not hard to have your short run in front of the feature -- if your company created both the feature and the short, that is. It also helps if you have other goals in mind than making money off the short...

"We look at our shorts as research and development for the studio in general," says Osnat Shurer, the exec producer of Pixar Studios' shorts program. "We're developing talent and giving people first-time leadership opportunities in everything: supervising animator, character lead or production designer in almost every film."

Shurer explains that the stakes are lower and the staffs are smaller on the shorts. "Supervising a crew of five people is a great opportunity to learn how to do that with a big crew on a full-fledged feature like Cars. She cites Doug Sweetland, who was supervising animator on Boundin', the short that accompanied The Incredibles, and moved onto to the same position on Cars.

"Not that Doug needed to be trained in animation, he's one of the top computer animators in the industry. It's that he had the opportunity to lead a crew, which is very different. You're looking to make a whole crew animate at something resembling your level, which is a pretty high bar in Doug's case. You're learning how to do bidding [estimating the time it will take to animate a shot] and balancing a production quota with the excellence you're looking for. If you're Doug it's going to take you a lot less time than one of the junior animators on your team. You have to learn how to work with that and help them along."

Pixar's shorts program serves as R&D for the studio and a way to develop talent. Doug Sweetland first supervised the animation on the short, Boundin' (above), before moving onto the same job on Cars. © 2003 Pixar.

>Pixar's shorts program has opened the door to some fascinating career moves for their creative staff. Lifted, the studio's newest short is directed by longtime sound designer Gary Rydstrom and will accompany Ratatouille into theaters next summer. "Gary had no directing experience before Lifted, but he had 13 Oscar nominations for sound design," says Shurer. "He's collaborated with us for many, many years on every Pixar film from Luxo Jr. up to Finding Nemo. Now he's moved onto directing side and will be doing a feature for us down the road."

Beyond the opportunity to deepen Pixar's own talent pool, Shurer considers shorts as a fundamental part of the animation medium. "It's something worthy of protecting," she says. "They're an opportunity for animators, independent animators, people who love the medium to express themselves. That's how we started, so we have a deep tradition of it here. We transitioned from a software/hardware company into an animation studio through short films."

Since Disney's acquisition of Pixar (and John Lasseter taking charge of the Disney animation studio), the Mouse House has followed Pixar's lead in establishing its own shorts program. "We talked to Osnat and the people at Pixar," acknowledges Chuck Williams, the director of Disney's new shorts program. "We saw there were great benefits to what they did. John and Ed [Catmull] said, 'Let's formalize it; let's do it at Disney.'" In addition to cultivating in-house talent, Williams cites "over-delivering" to the audience and avoiding sameness in the features as benefits of a shorts program. "You can tell different kinds of stories, explore different narrative and animation techniques, and artistically get out of your comfort zone. It's a great way to stay in touch with the animation community at large."

In recent years and prior to the new program, Disney produced several shorts including Mike Gabriel's Lorenzo in 2004, and 2003's Destino, bringing a 1940s Dali/Disney collaboration to fruition. "You can even look at Fantasia 2000 as a collection of shorts," Williams muses. "They were all done with same spirit. What we've done with the new leadership is formalize and recognize it as something healthy and worthy of doing."

According to Williams, "the enthusiasm the people here had for the program was incredible. During the first round of pitches this summer we saw 150 ideas over two months -- 55 people came forward to pitch. It wasn't a gong show approach either -- your three minutes are up, thank you very much. People had a half hour to pitch three ideas. They would get notes, they could pitch a second or third time and watch other people pitch to demystify the process."

Eighteen ideas were eventually reviewed by Lasseter. Six of them made it to the story reel stage, from which two were greenlit -- a classic-style Goofy short, How to Hook Up Your Home Theater, co-directed by Kevin Deters and a woman who will become Disney's first female director, Stevie Wermers. The second short comes from Chris Williams, a writer on Mulan and Emperor's New Groove and no relation to Chuck. The CGI-rendered Glago's Guest sounds as unlike a classic Disney short as possible, with its story of a Russian soldier manning a Siberian outpost. One of the two shorts will accompany American Dog, the studio's 2008 release.

"This is our future," Williams sums up. "The young filmmakers doing shorts are the ones you're going to see [directing features] five or six pictures down the road. From a money standpoint I look at it as a creators' 401k. We're investing for the future in our shorts program."

Since Disney's acquisition of Pixar, the Mouse House has followed Pixar's lead in establishing its own shorts program. In the past, Disney produced Lorenzo, directed by Mike Gabriel. © Disney.

New York's Blue Sky Studios, creators of Robots and the Ice Age, features first made a splash with its Oscar-winning 1998 short Bunny. "It took eight years to make Bunny, recalls writer/director and studio kingpin Chris Wedge. "It wasn't made as a calling card, but it did help us focus and develop advanced rendering software like our radiosity renderer." Like Disney and Pixar, Wedge looks at his studio's shorts program as "a focus for developing creative talent."

Pixar's shorts precede its features in the theaters and accompany them on its DVD releases (as Boundin' did with The Incredibles, or One Man Band with Cars). In addition, the studio's DVDs include an original bonus short or two starring the film's characters. On the just-released Cars DVD, Mater the tow truck returns in Mater and the Ghostlight, while on The Incredibles DVD, Jack-Jack Attack reveals what's taking place back home while the family's out adventuring. A second, hysterically funny Incredibles short features a "commentary track: from Mr. Incredible and Frozone (Craig T. Nelson and Samuel L. Jackson, as their movie characters) fulminating over Mr. Incredible and Pals, a cheesy TV cartoon supposedly based on their adventures.

Destino brought a 1940s Dali/Disney collaboration to fruition. © Disney 2002.

Shurer admits that, "all of us fall in love with the world and the characters we create. Spending more time with them there is the strongest motivation, but it's also nice to be able to include something exclusive to the DVD. It's a chance for the audience to see a little more of that movie's world -- and it gives them a reason to buy the disc."

Adding an original short starring the film's characters (or breakout character) as an incentive to buy the DVD is now standard operating procedure, from Mater to Ice Age's Scrat and Madagascar's penguins. When it was Over the Hedge's turn, "everyone gravitated to Hammy because he was a real sticky character," reports Will Finn, referring to the movie's manic, Steve Carell-voiced squirrel. As one of Hedge's storyboard artists (and with directing credits at Disney and DreamWorks), Finn was tapped to direct Hammy's Boomerang Adventure. "I was sort of the default director for ancillary things. After four years the directors took hiatuses as soon as post-production ended. I knew the movie and the characters were a lot of fun to work with. I wasn't in any hurry to say goodbye to them."

Unlike the studio's Christmas-themed theatrical short starring the Madagascar penguins (who are slated to star in their own Nickelodeon TV series), DreamWorks looked at the Hammy short as strictly a DVD extra. "We needed to do something economical. We had to make this brief and stick to existing characters." The solution was a Punk'd-style spoof seen through the viewfinder of a video camera as Hammy battles a boomerang that won't leave him alone. Finn was fortunate enough to piggyback onto the movie's final recording sessions and get all his dialog from the original performers. "They had a bit of a glassy-eyed look-- after four years, it was like 'we're not done yet?'"

Lifted is the newest short to come out of Pixar. Oscar-winning sound designer Gary Rydstrom moved into directing with Lifted and will soon be directing a feature for Pixar as a result. © Pixar Animation Studio.

Between young and hungry independent animators working on their labors of love, and CGI studios cranking out high-profile and high-budget prestige pieces, there's no shortage of shorts to choose from. Smith sees the overall quality of the independent shorts as on the upswing. "There's a nice combination filmmakers have been achieving: professionally produced, very cinematic efforts that still have the human touch and a single-minded director's vision."

Smith goes on to view lengthier efforts like John Canemaker's Oscar-winning The Moon and the Son (clocking in at close to 30 minutes) and Chris Landreth's 14-minute long Ryan as exceptions rather than forerunners of a trend. "It depends on the subject matter. Would Canemaker's film work in five minutes? He needed that half hour. Dialog films run longer -- it takes time to say stuff. Pantomime that's based on a simple idea tends be shorter."

In the age of YouTube, podcasts and Flash animation, no one should overlook the Internet's potential to earn a superior piece of work widespread attention. On the Cartoon Brew website, Amid Amidi recently reported on the amazing success of Kiwi! a poignant, funny and brilliantly realized thesis film by New York SVA student Don Permedi:

"It is currently the most linked-to video on the blogosphere according to Technorati.com, it's in the top 15 all-time favorite videos on YouTube, and it's racked up nearly two million views in the past week."

Two million views in just seven days... as a calling card alone, it would be surprising if Kiwi! fails to open career doors for Permedi. Internet visionaries have long spoken of creating a system of "micropayments" to help artists make an online living. Imagine those two million people parting with a penny each to view a cartoon like Kiwi!; when and if that day arrives, there will be no shortage of animators earning a living from their short creations.

Joe Strike is a regular contributor to AWN. His animation articles also appear in the NY Daily News and the New York Press.