Kung Fu Panda co-director Mark Osborne reminisces about mentor Jules Engel, who will be honored with a centennial celebration at CalArts on Saturday. Osborne will participate in a roundtable discussion about Engle's influence on contemporary animation.

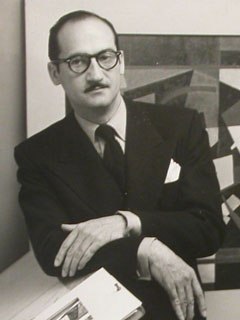

Jules Engel in his studio, 1949. Courtesy of Tobey C. Moss. Photo credit: Lou Jacobs Jr.

In the fall of 1990, I transferred into the Experimental Animation department at CalArts after studying foundation art at Pratt Institute in New York. I had a sense that I was entering into a unique program. Judging from the work on the walls, I knew this was a place where special and interesting things had happened in the past. Walking around the room, I could see interesting work in progress on every desk. It wasn't until I started taking classes that year, however, that I truly understood that the foundation for all of the work I saw was in large part due to the amazingly supportive environment that was created for these students by my mentor Jules Engel.

Whether he was teaching the fundamentals of animation, showing us incredible and rare films from all over the world or just sharing his own body of work, Jules was a kind and constant force for good. To be honest, it took me quite some time to realize just how incredible he was since I was young and not ready for all he had to offer. I came to CalArts hoping to learn enough about animation to land a job on The Simpsons, but what I discovered through Jules' example was that there was a whole universe of possibilities in animation and that as a means of personal expression it was unparalleled. I was hooked on the idea of exploring anything and everything it had to offer, hoping that I could follow in his footsteps and the other faculty in striving to make films "of consequence." It's something that stays with me almost every day in my work. Am I doing something worthwhile here? Is there a good reason for me to spend all this time, energy and resources on this project? If the answer isn't yes, I refocus and find a way to get there.

Once I started to open my mind, I tried to write down a lot of what Jules said so that hopefully in time I could have a chance to fully comprehend the wisdom he imparted with each class. Primarily, his personal work was a tremendous inspiration to all of us artistically. The majority of Jules' work was what would be described as "visual music." Each film was a three to five minute poetic, abstract expression of an idea or theme. Each also had such a strong character of its own. Each one was like a different painting from the MOMA brought playfully to life. Jules would explain to us where each work came from and what was in it personally for him. With each example, I could begin to see how big ideas could be explored, yet boiled down into the simplest of expressions. There was such joy and abandon in his work; each film being a new world onto itself.

Jules' work on Fantasia (1940) is a lasting example of his "visual music" style of animating. © Disney Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved.

Jules' relentlessly positive attitude toward his overall artistic expression is what I found the most encouraging and enlightening when it came to thinking about animation. Jules showed me that the possibilities in animation were far greater than I had ever realized and an artist had to find a personal reason to drive his or her work. Animation could be more than just cartoons, even though Jules loved them too.

Jules encouraged all of us greatly to try things whether he understood what we were after or not. He challenged us to confuse him. If he didn't get what we were doing, he knew we were potentially onto something unique and would enthusiastically encourage us to keep going. Sometimes we'd fall on our faces, but he'd give us the courage to get up and try again. It wasn't important that what we did pleased him, but that we discovered something on our own. Like a good therapist, Jules knew that we had to find our own answers.

I eventually learned that in his professional work, Jules was able to apply the same passion and artistic integrity that imbued his own films with such vitality. When he showed us examples of the work he was hired to do, I could still see his stamp. It was very enlightening how he managed to translate his personal expression into his studio work for UPA and other clients. This spoke volumes about the importance of bringing your own point of view to the process, no matter what the assignment. Later, as I took on work for hire, I found his example to be a great one. I continuously checked in with myself to make sure I was bringing a strong point of view. In a collaborative environment it is not always welcome, but I do believe it does make for better work. When I think of Jules' influence on my work, I certainly see that as the clearest and most valuable example he set for me.

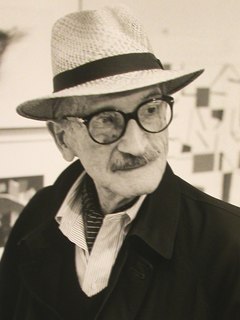

Jules Engel at his exhibition at the Tobey C. Moss Gallery 2001. Courtesy of Tobey Moss. Photo Credit: Mark Kirkland.

One of the most interesting things about Jules that has always stuck with me was that he ended every class by saying "I love you all." At first I thought this was weird, and he had a thick accent so I thought it was just some European thing. Over time I came to realize that this was a pure expression of his supportive style as a teacher and mentor. His positive energy and unconditional love was exactly the right thing for those of us struggling to find our voices, for those frustrated with the process of animation, for those trying to figure out their place in the world. That expression of support and kindness sent out a ripple across the campus.

On the flip side of that, I remember one day he had just gotten back from seeing Martin Scorsese's Goodfellas. He was so angry. Jules went on a terrific rant about how horrible an expression of humanity that film was and that nobody needed to see anything like that. He was so disheartened by that film and wished it wasn't out there in the world. It was as if everything he stood for was threatened by it, that he would have to work even harder to be a positive influence on us filmmakers so that we would go out and celebrate humanity and beauty, just like he had wished to do in his own work.

Simply put, Jules -- as well as the rest of the faculty -- created a safe place where we could fail. We could try our best and no matter what happened, we knew we'd still be loved. More often than not, that environment fostered great personal success.

Jules Engel was a fantastic force for good and continues to be a true inspiration to all that knew him. As a mentor and an artist, Jules has a tremendous lasting effect on the world and on films that are being made today.

CalArts will host a Jules Engel Centennial Celebration on Saturday, April 18. Go here for more information.

Mark Osborne co-directed DreamWorks Animation's Oscar-nominated Kung Fu Panda with John Stevenson. His acclaimed short, More, examined mid-life crisis, reawakening the "fire in the belly" and the perils of seeking success, garnering an Oscar nomination for Best Animated Short. Osborne earned his BFA in experimental animation from CalArts, where he later returned as an instructor for advanced stop-motion filmmaking. He currently has various personal projects in the works, and was awarded a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship to assist in the production of his latest stop-motion short.