Taylor Jessen looks at the load of recent releases celebrating the art of Winsor McCay, including the reissue of John Canemakers Winsor McCay: His Life and Art, the comicstrip collection Little Nemo in Slumberland: So Many Splendid Sundays and the Winsor McCay: The Master Edition DVD.

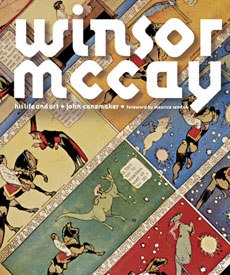

Animator and academic John Canemaker has reissued his comprehensive bio Winsor McCay: His Life and Art.

Give a kid a train set and watch him go to town. When Orson Welles had Hollywood served to him on a silver platter in 1939, he took all the filmic toys set before him and made Citizen Kane. Likewise, when publisher James Bennett gave up-and-coming cartoonist Winsor McCay a page all his own every Sunday in the New York Herald starting almost exactly 100 years ago, Winsor claimed every square inch. He called his new full-page, full-color art nouveau adventure Little Nemo in Slumberland. In the end, Little Nemo didnt just bring McCay and his paper artistic and financial success it shouldered the whole comics medium into the ranks of High Art. Comics and comic artists have been trying to live up to the accolade, and to Little Nemo, ever since.

October 2005 marked the centenary of Little Nemo, and, thanks to renewed interest in McCay and his work, its never been easier to see artifacts of McCays masterwork in living color. America and its libraries hate old newsprint, as chronicled by Nicholson Baker in his incendiary Double Fold, and no one in 1905 expected a day-old news rag to fulfill duties beyond that of fishwrap. And yet, despite 10 decades of general apathy, a few dedicated preservationists have saved Little Nemo and the rest of McCays bibliography for posterity.

Most comic artists have at least a passing acquaintance with the Little Nemo strip, and animators are hip to McCays groundbreaking short, Gertie the Dinosaur but did you know McCay invented the horror comic? That by 1921, two years before Disney signed the contract to make his Alice comedies, McCay had produced three science fiction animated shorts whose draughtsmanship alone wouldnt be matched until 1937s The Old Mill?

Most comic artists have at least a passing acquaintance with the Little Nemo strip and animators are hip to McCays groundbreaking short Gertie the Dinosaur (above). © 2003 Milestone Film & Video. All rights reserved.

Animator and academic John Canemaker, author most recently of The Art and Flair of Mary Blair, has just reissued Winsor McCay: His Life and Art, a comprehensive bio of McCay informed by unique and wonderful raw materials from the late artists estate. A Canadian native, Winsor Zenas McCay was born in 1867 and had his first commercial art job in 1889 making circus posters in Chicago. After a decade spent pumping out advertising ephemera for local Dime Museums, two Cincinnati newspapers took him on as staff, and his employers and the general public quickly discovered he had an unmatched gift for perspective drawing.

McCay had an almost otherworldly ability to draw scenery and characters from top to bottom without pencil roughs, his strokes interrupted only by ink refills, and Canemakers book proudly displays crisp reproductions of dozens of examples of the masters best illustrations.

In 1903, McCay was discovered by the New York papers, and he worked for two competing sheets at once, creating childrens comics for one and adult strips (under the pseudonym Silas) for the other. For the Evening Telegram, he created Dream of the Rarebit Fiend and A Pilgrims Progress; for the Herald he invented Little Sammy Sneeze, The Story of Hungry Henrietta and, finally, Little Nemo in Slumberland, which ran continuously from 1905 to 1911 until McCay was lured afield by William Randolph Hearst.

Reading Little Nemo today, its amazing enough that it played out as a single ever-evolving storythread for years at a time with no continuity gaps, or that McCay allowed the narrative to build for a solid four months before he even allowed Nemo to reach Slumberland. What may blow your fuse is the cumulative effect of reading all of Little Nemo in sequence its enough to bring on a species of thunderstruck joy. Its a longer, more convivial version of Sam Lowrys breathless dash at the end of Brazil, running from fantastic exterior to fantastic interior in a never-ending progression of architectural whammies.

(The complete nine-year run of full-page strips was collected by Taschen America in the 2000 book, Little Nemo: 1905-1914, now out of print. Finding it used is a minimum $200 investment, but its worth it for the Mars sequence alone. Nemos trip to Mars ran through the spring and summer of 1910 and represents McCay at the height of his powers, combining social commentary, vertiginous urban landscapes, fantastic creatures and delicious color schemes in a sine qua non of spectacle.)

Little Nemo hit hard and spawned heavy merchandising as well as a spectacular stage musical. McCay himself became a celebrated solo performer, and, after working crowds as a simple quick-sketch artist, he pushed the boundaries of his art even further by showcasing his own animated film, Gertie the Dinosaur, as part of his vaudeville act. After McCay moved to Hearsts New York American, however, he found all these artistic avenues unexpectedly stifled. Hearst insisted McCay not tour with his vaudeville act, he was cool to the point of hostile about McCays animation projects, and he insisted that McCay pour his energy into single-panel editorial cartoons to support the humorless and reactionary rantings of the papers head editorialist.

McCay finally outlived his contract in 1924, but by then it was too late his career as a pioneering cartoonist and animator was in the past and his popularity was on the wane. He died 10 years later.

Canemaker first published his McCay biography in 1987, and, this year, his coffeetable book was reissued in an expanded edition that animators everywhere need. Winsor McCay: His Life and Art includes not only a fresh retelling of the artists life, but also a generous sampling of his lifes work in ultra-sharp reproductions from the original artwork. Now that McCays oeuvre is public domain and its easier than ever to find reprints made from copies or copies of copies as is the case with the abundant but erratically curated Winsor McCay Early Works series from Checker Book Publishing Group Canemaker has wisely filled his book with primary sources, most lent from McCays own estate.

In revising the book, hes actually removed many full-color reproductions of Little Nemo strips from the previous edition a good call, since theyre now available elsewhere and instead the juice comes from the many press clippings, family photos and examples of merchandising demonstrating the reach of Little Nemos popularity.

Winsor McCay: The Master Edition contains all of McCays surviving animated film work lovingly restored from the cleanest surviving elements. Included are McCays innovative Little Nemo and Gertie the Dinosaur.

All essential reading so far, and we havent even got to his darkly funny Rarebit strips yet, the discovery of which is the best part of coming to Winsor McCay for the first time. If you think McCay was a great draftsman who never got past drawing children in balloons, consider that his Dream of the Rarebit Fiend strip concerned, to take a few cute-free topics at random dismemberment, cannibalism, elephantiasis, train derailments, deranged cable car conductors, falling, forgotten speeches, live burials, insanity, runaway obesity, drunkenness, extreme hair restoration and live organ transplants.

McCays proto-Twilight Zone fantasy strip has a simple open-ended premise: Day after day another anonymous citizen has a nightmare after eating Welsh Rarebit just before bed. In one strip McCay depicts a child in bed who cant move as creatures from all over the animal kingdom start nesting in his mouth and nose; in another he draws a bed taking flight and throwing its unwilling occupant into the cold night air. And, in a classic of the genre, McCay lends eight panels to illustrate a misers death and burial, all from the corpses point of view, as the widow gives a not-so-fond farewell and the funeral guests take turns cruelly and hilariously badmouthing him. (He looks natural, but who wouldnt with the alcohol thats in him?)

Canemakers book includes lavish reproductions of Rarebit Fiend strips and other McCay creations, and, for the uninitiated, its a great springboard into an amazing journey of discovery. That jumper should next land on the DVD Winsor McCay: The Master Edition from Image Entertainment and Milestone Film & Video. The 2003 disc contains all of McCays surviving animated film work, including his innovative Little Nemo, Gertie the Dinosaur, How a Mosquito Operates, The Sinking of the Lusitania and his Rarebit- inspired shorts Bug Vaudeville, The Pet and The Flying House all lovingly restored from the cleanest surviving elements.

Sunday Press Books presents Little Nemo in Slumberland: So Many Splendid Sundays at its original broadsheet size.

McCays animated short, Little Nemo from 1911, is charming on its own, but in the context of its time its downright shocking. Half a decade before the toon industry with its rubberhose aesthetic and assembly-line production values started banging out Felix the Cat and a dozen lesser copycats, the hand-colored Little Nemo short set a standard so high no one bothered to challenge it for decades.

Besides offering a chance to revisit our friend Gertie, precocious reptile and progenitor of character animation as we know it, the DVD is just as valuable for preserving the works that should have put McCays name in the same sentence with Walt Disney throughout the 1920s but didnt. The Pet in particular is an eerie tale of a family pet that grows out of control and eats everything in its path until it is destroyed, and the city along with it, in an air strike. The animals terrified visage staring out from between rows of tall buildings is a strange progenitor of Akira. The DVD is comprehensive and includes rare fragments, a documentary short, and commentary by Canemaker.

There are several ways to set eyes on original Little Nemo strips, either via the aforementioned Taschen book or a similarly out-of-print multi-volume collection from Fantagraphics; but the most interesting option of all just became available from Sunday Press Books. Little Nemo in Slumberland: So Many Splendid Sundays is 16" wide, 21" tall, and 120 pages thick, and, barring ripping off the archives of the New York Public Library, it is the only way of seeing Little Nemo strips at their original broadsheet size. Purportedly digitally restored with a handpicked selection of the best of the series, I havent actually seen whats inside this book because all the copies at Meltdown Comics in Hollywood are shrink-wrapped. Likewise Golden Apple in L.A. had three of this $120 behemoth all of which went out the door the same day.

Act now, say these statistics, for only 5,000 copies exist. Barring a local source, ordering direct from Sunday Press Books website may be the only way to get this highly coveted treat this holiday season.

Little Nemo and all of McCays work continues to infect todays artists through means they never would suspect. I grew up with Maurice Sendaks In the Night Kitchen, but until reading Canemakers book I never sussed that Sendak took his visual cues and dialogue (Mama Papa!) specifically from the Thanksgiving episode of Little Nemo from Nov. 26, 1905. Little shards of Little Nemo continue to fall into todays art like dust from outer space.

Unfortunately there are several things blocking a full-fledged renaissance of McCays work, most of all the language. His dialogue conforms to a turn-of-the-century urban patois whose spoken cadences we can only guess at (Oh! Theres the Candy Kid. Come Flip, we are going to land! Oh! Im so glad! Um!) Much of his verbal technique is anathema today, from unnecessary verbosity to his tendency to continue sentence fragments from one word balloon to the next across frames a no-no that plays hell with the rhythm of the modern reader.

McCay was the worlds first independent animator; he was an industry of one.

Theres probably no future in film adaptations of McCays work, either, if Tokyo Movie Shishas ill-advised 1992 anime, Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland, was any indicator. McCays was a solitary art, and perhaps thats why its resisted adaptation over the years, despite the wonder that Little Nemo will always inspire or the wealth of ideas waiting to be mined in Rarebit Fiend or Pilgrims Progress. McCay was the worlds first independent animator, and todays independents can take solace from the fact that he never made a living off his shorts either. He never intended to, for he was an industry of one, a lone artistic force who famously told an audience of professional animators in 1927 whod gathered to fete him that what you fellows have done with [animation], is making it into a trade. Not an art, but a trade. Bad luck!

Winsor McCay: His Life and Art by John Canemaker. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2005. 272 pages with illustrations, 40 in full color. ISBN: 0-8109-5941-0 ($45.00).

Winsor McCay: The Master Edition DVD, Image Entertainment/Milestone Film & Video, 2003. 110 min. B&W and hand-colored, stereo, NR. UPC 014381198225 ($29.99).

Little Nemo in Slumberland: So Many Splendid Sundays by Winsor McCay; edited by Peter Maresca. Palo Alto: Sunday Press Books, 200 pages. ISBN 0-9768-8850-5 ($120.00).

Taylor Jessen is a writer living in Burbank. He is currently consulting with Icy Sweet Novelties of Sunland, California, for whom he is sequencing the complete works of Milhaud, Stravinsky, Debussy, Satie and Ravel for playback on their ice cream trucks.