Adam Beckett’s tragically short career as experimental animator and budding effects master are celebrated in a collection of his restored films.

A young artist, a career full of promise, a life of innovation and energy tragically cut short. Such a summary barely begins to describe the bright, fast burn that was rising star Adam Beckett (1950-1979), one of the first graduates of the CalArts Experimental Animation program, and a prolific animator, sketch artist, and effects prodigy. Known for his unique abstract film loops, as well as for his precise, yet organic work with the optical printer, Beckett’s work continues to influence young animators both at his alma mater, where he is frequently mentioned, as well as in the wider animation world.

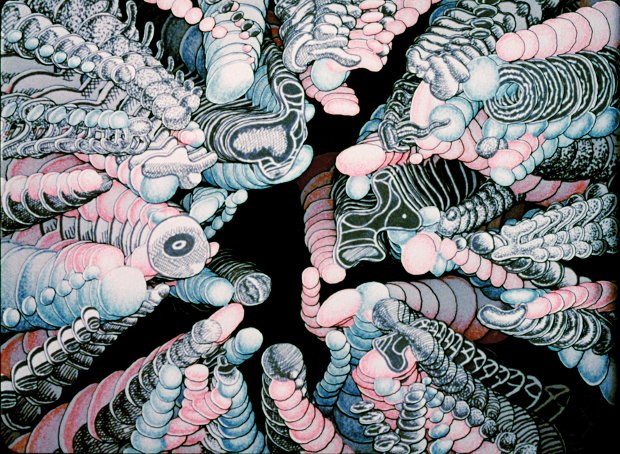

Many in mainstream animation, however, may be unfamiliar with the name Adam Beckett. That could very well change in the near future. Thanks to the contributing efforts of Beckett's family and friends, the iotaCenter has spent over 8 years on the Adam K. Beckett Project, conserving and preserving Beckett’s film material. Their restoration efforts have culminated in exhibitions and screenings at The National Gallery of Art, The Academy, and L.A.’s own REDCAT. Now, the iotaCenter has produced a comprehensive DVD as part of their Kinetica Video Library. The resulting compilation, which covers the years 1970 to 1979, includes both published and unreleased work, Beckett's film loops, and additional photographs and documentary material. Among the disc’s bonuses are his collaborations with James Gore, and a gallery of Beckett’s drawings, some of which have visible char marks, a somber reminder of the house fire that took the young animator’s life.

From the sheer volume of material left behind, and the number of former colleagues and classmates willing to be interviewed by Pam Turner, who headed up iota’s research, it is clear that Beckett’s short life was a full one. Before joining the then-new Experimental Animation Program at CalArts, Beckett had studied mathematics. A seemingly incongruous link, his ease with numbers and abstractions would prove essential, and made him a natural when it came to manually exposed and re-exposed animation.

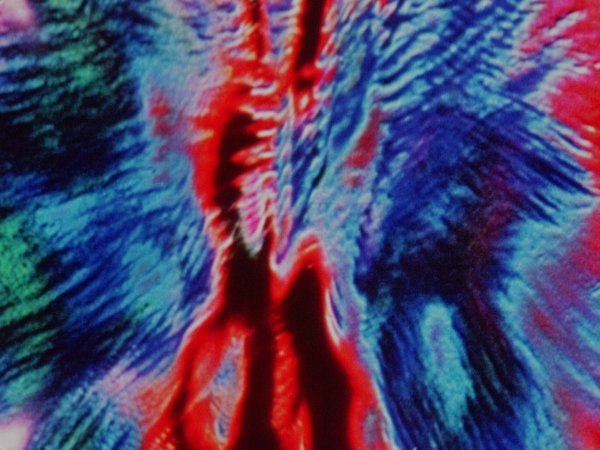

Appropriately, Beckett's earliest works are very much a representation of the direction of Jules Engel's Experimental Animation program in the early 1970s. Engel, a former animator at Disney, and later UPA, was at that point a dedicated abstract expressionist whose interests were concentrated in visual music and painterly, geometric animation. The influence of this iconic program chair can be felt in early Beckett pieces like the musically-driven Dear Janice, with its mixture of abstract cycles, words, sexual imagery, and live footage, or in Kitsch in Synch, where playroom shapes build and build in time to a nonsense chant that grows from child-like voices to wild cacophony. Never content to repeat himself, Beckett’s films show a range of techniques, and a continuous expansion of his past discoveries. Works such as Evolution of the Red Star, with its cycling, multiplying shapes, color tinting, and playful use of the animated frame, or Heavy Light, with its energy trails optically printed on black, showcase Beckett’s sense of experimentation and personal evolution. The figure makes an appearance, too, memorably in the pornographic, yet placid, Flesh Flows with its homages to Schiele and Dali enveloped by pulsing, gradually distorted imagery.

Besides a wealth of finished short films made at CalArts, the Beckett collection includes footage and related clips from his last, unfinished film, Life in the Atom. Restored in 2009 by Mark Toscano and the Academy Film Archive, Life in the Atom, like Sausage City, calls attention to the space of the animated frame by showing the surrounding Oxberry stand (still existent at CalArts to this day) the film was shot on. The surviving footage shows more of a focus on the detailed, figurative image than his completed works, as well as a denser, more saturated spotting of color. There are recurring themes here, like the sexual imagery and cycles in Flesh Flows, but there is a decided sophistication to the rendering and timing. It is a testament to the tragedy of losing Beckett that we will never know what direction he may have been heading in next.

In many of the shorts, Beckett’s focus is on rhythm, and on new configurations of repetitive movement and morphing shapes. There is a real sense of play, and of direction, in pieces that would otherwise appear to be exercises. Largely, what immediately moves Beckett apart from his contemporaries is his utilization, and ability to push, the technology available. In his work, Beckett displays an easy mastery of the optical printer, used to create multi-layered effects that, at the time, were a far cry beyond what was capable using a single or multi-plane downshooting rig. For those unfamiliar with the technique, an optical printer is a device that links one, or several, film projectors to a movie camera, allowing for the re-photographing, layering, and alteration of film. Its best-known use has historically been in movie special effects, but it has been a boon to the experimental animation and fine art film worlds since the first was constructed in the 1920s. Beckett’s experiments with the optical printer are a continuation of a legacy that includes filmmakers as varied as Oskar Fischinger, Norman McClaren and Harry Smith. What would today be considered an easy trick thanks to the Adobe Suite is, in the context of the 1970s, an example of an experimental spirit meeting technical wizardry. As we see in Beckett’s case, this understanding of the optical printer’s range of uses straddles both the art and VFX fields.

Shortly after graduating from CalArts, Beckett went to work at Industrial Light & Magic. His previous experiments with the optical printer, particularly the so-called Knotte Grosse Experiments, and his tinkering with the roto camera setup at Lucasfilm paid off, as Beckett was put on visual effects development for a new science fiction film called Star Wars. Archival footage from 1976-77 taken at ILM shows Beckett, Mike Ross, Pete Kuran, and others pouring over what to this casual observer seem to be frames from the Death Star explosion that caps the film’s climax. The crew isn’t all work, as the soundless Super8 shows, but full of guitar-playing breaks, parking lot antics, and an office party. Beckett appears in-frame quite a bit, seeming reserved but social, well-liked, and always up for a laugh.

Beckett’s clear professional accomplishments alone would merit remembrance. As a graduate from the same program as Beckett, where his name is still known, it strikes me that just as remarkable as his technical expertise is the experimental spirit his work exemplifies. In the variety and in the impressive production of his work, Beckett shows a feverish, irrepressible desire to create, to push himself, and to grow. His characteristic willingness to prompt his own artistic evolution is as important an example to current animators as the technical content of his pieces.

In the DVD collection is an interview with the late Jules Engel about Beckett. Engel remembers Beckett as eager to work, recalling that Beckett had shown up ready to shoot a month before the school had officially opened. “He would go into the Oxberry room at 8 in the morning, and come out at 10 at night,” remembers Beckett’s former teacher. He speaks of a passionate drive that would keep Beckett working for days at a time, and of the almost obsessive need he had to complete his films. Certainly, he says, Beckett could be considered influential at the time, as he was making work unlike anything that had been seen before. In order to remain influential to future generations, “he has to be seen,” Engel states emphatically. While major museums keep the Old Masters alive by displaying their work, it is access to viewing films that keep artists like Beckett present in today’s animation world. A collection such as the one iotaCenter has put together begins to service that need. Adam K. Beckett: Infinite Animator both celebrates Beckett's achievements, and provides future generations of animators and scholars with access to his unique, inspirational work.

--

A heartfelt thanks to Larry Cuba and Paul Shephred at the iotaCenter for answering additional questions and providing photographs, and to the entire team for their hard work on the Beckett project. Read more about their conservation efforts, and other iota projects, at http://www.iotacenter.org.

You can purchase the Adam K. Beckett: Complete Works 1970-1979 dvd at http://www.iotacenter.org/store/videos/beckett_dvd.

Zoe Chevat is a Los Angeles-based animator, graphic artist, sculptor, and author of both academic and fictional work. Originally from northern New Jersey, she graduated from Bennington College and is currently an MFA candidate in Experimental Animation at CalArts. She has worked on music videos and shorts for AfterEd TV, UnBroiled Inc., and Ariel Hart/DeMille Productions, as well as the anthological Today's Forecast, which debuted at the Internationale Kurzfilmtage, Oberhausen, Germany. A proud cinephile, she has been blogging about gender and film/video media for female geek-oriented newsblog The Mary Sue, and has been a recurring guest on a new podcast series for Anime News Network, entitled "Chicks on Anime." Most of her critical writing is concerned with the portrayal of sexuality and gender in genre work, with a particular focus on trope subversion for fun and profit. She provides a ground-level insider's view on the new generation of animation fans and creators, with an eye to negotiating that tricky space between high and low art…or at least to rattling some cages along the way. For more rants, spewings, and inky scribbles, follow along at http://www.zoechevat.com.