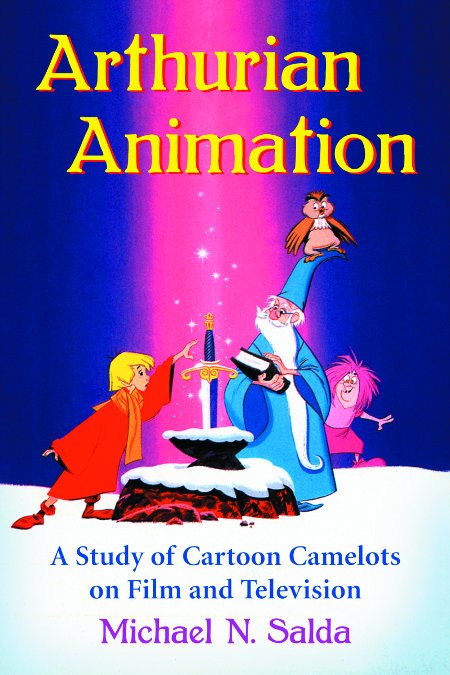

Fred Patten looks at the definitive new guide to Arthurian legends and themes in animated works.

Jefferson, NC, McFarland & Company, July 2013, trade paperback $45.00 (220 pages), Kindle $16.49.

King Arthur and Arthurian themes are always popular, aren’t they? And animated cartoons have always featured popular themes, if only for comedic purposes, haven’t they? So you would assume that animation about King Arthur and other elements of the Arthurian legends have been constant since theatrical animation began.

Michael N. Salda says that you would be wrong, in this well-documented history of what he calls “Arthurianimation”. In fact, the earliest Arthurianimation that he has found is Leon Schlesinger/Warner Bros.’s 1933 “Bosko’s Knight-Mare”. There were no cartoons with Arthurian themes during all of the silent film period! And “Bosko’s Knight-Mare” was specifically made to capitalize on the popularity of Fox’s 1931 theatrical feature adaptation of Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, starring Will Rogers; not on Arthuriana in general.

Salda is an associate professor of medieval literature in the Department of English at the University of Southern Mississippi. He has been interested in Arthurianimation since the 1990s, when a colleague, the editor of the 1991 Cinema Arthuriana: Essays on Arthurian Film, suggested that he write an essay on Arthurian animated cartoons. That was Salda’s “‘What’s Up, Duke?’ A Brief History of Arthurian Animation” for a 1999 followup collection of essays on Arthurian cinematography. Salda has continued to expand his research into Arthurianimation, and this book is the result.

Arthurian Animation: A Study of Cartoon Camelots on Film and Television is excellently researched, but Salda’s conclusions are ultimately depressing. He shows that the first Arthurian-based cartoon was made to take advantage of a popular 1931 movie adaptation of Twain’s humorous A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, and that almost all subsequent cartoons have been to take advantage of some other momentary popularity of Arthuriana. A brief flurry of 1950s and early 1960s animated cartoons – Warner Bros.’ “Knight-Mare Hare”, and “Knights in Armor” motifs in early Hanna-Barbera and Jay Ward TV cartoons – took advantage of such 1950s live-action features as Knights of the Round Table (1953), The Black Shield of Falworth (1954), The Black Knight (1954), the movie adaptation of the newspaper comic strip Prince Valiant (1954), The Court Jester (1955), and many others. Disney’s 1963 animated feature The Sword in the Stone followed the popularity of the 1960 Broadway hit Camelot. And while The Sword in the Stone is generally considered the first of Disney’s lackluster feature-length cartoons such as The Aristocats (1970) and The Fox and the Hound (1981), Salda harshly proclaims it a “Full-length Flop”. Practically all Arthurianimation contains some flaws in Salda’s estimation – most deliberately so, since their purpose is comedy and the satirization of Arthurian ideals.

Where Arthurian Animation: A Study of Cartoon Camelots on Film and Television excels is in Salda’s exhaustive list with plot synopses and analyses of every(?) Arthurian or Knights in Armor cartoon ever made, for theatrical, television, film strip, educational classroom use, or other purposes. (Salda does not quite claim that his list is complete, but he cites his and his research assistants’ years of research, and invites readers to send him information about any cartoons that he may have missed.)

Chapter 1 is devoted to a nine-page description and analysis of “Bosko’s Knight-Mare”, since it was the first of all. Chapter 2 is “The Best Arthurian Cartoon Never Made: Hugh Harman’s King Arthur’s Knights”; about the veteran animator’s failed attempt to start a new studio and to make a serious feature-length cartoon during the early 1940s. Subsequent chapters relate the flurry of theatrical and TV cartoons during the 1950s and early 1960s, culminating in Disney’s disappointing 1963 The Sword in the Stone, and Arthurianimation’s slow decline until popular interest in Arthuriana was rekindled by Monty Python and the Holy Grail in 1975. Since then, Arthurianimation has been steadily with us, and Salda covers everything, from the features like Warner Bros.’ Quest for Camelot (1998) and DreamWorks Animation’s Shrek series (which are technically CGI, not cartoon animation), to the made-for-video children’s movies like Tundra Productions’ 1998 Camelot: The Legend, to individual episodes of TV cartoons like Animaniacs and The Simpsons and The Fairly Oddparents and SpongeBob SquarePants that parody Arthurian stereotypes.

Salda’s scope is international. The 1979 Japanese 30-episode animated TV series King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table? Pages 82 to 84. The 1968 Australian Arthur! and the Square Knights of the Round Table? Page 70. Salda points out that the 1960 Japanese feature Alakazam the Great, which was a straightforward adaptation of the classic Chinese Monkey King folktale, was given some Arthurian names such as “Merlin the magician” for an old wizard in the American 1961 release dub.

If it’s about King Arthur and it’s animated, it’s here. Some of the entries are long on plot synopses and short on critical analyses, but something like a four-part adventure in The Underdog Show (1965) does not deserve deep analysis. Arthurian Animation: A Study of Cartoon Camelots on Film and Television is engrossing reading for the animation fan, and a handy reference tool for those who want to know anything about Arthurian animated cartoons (and CGI). The book includes many still reproductions and framegrabs, movie posters, and home video box covers. There are extensive notes, a list of works cited, and an index.

--

Fred Patten has been a fan of animation since the first theatrical rerelease of Pinocchio (1945). He co-founded the first American fan club for Japanese anime in 1977, and was awarded the Comic-Con International's Inkpot Award in 1980 for introducing anime to American fandom. He began writing about anime for Animation World Magazine since its #5, August 1996. A major stroke in 2005 sidelined him for several years, but now he is back. He can be reached at fredpatten@earthlink.net.