Jim Korkis chronicles the birth of animation training, which came about through the studios as they grew into longer and longer productions.

Today, an aspiring animator has many opportunities to learn the necessary skills of his chosen profession from college classes to a variety of books to magazine articles and even teaching resources on the Internet. The eager student also has access to other trained professionals who can guide him effectively in knowing the basic concepts of animation that he would need to study and practice.

However, things were much different almost a century ago when aspiring newspaper cartoonists struggled with a new entertainment form known as animated cartoons.

Originally, animation was a novelty like a magic trick. Less demanding audiences were greatly entertained by the mere fact that drawings moved or performed an occasional slapstick gag. Animation was considered a product and not an art.

Animators at the Paul Terry Studio, which produced some of the most popular cartoons that even influenced a young Walt Disney, remembered Terry wandering through his studio with a ruler. When the stacks of drawings reached an arbitrary mark on the ruler, Terry declared the cartoon finished and work to begin on the next cartoon.

The first, and for a long time only, book on animation was Animated Cartoons: How They Are Made: Their Origin and Development by Edwin George Lutz. It was first published in 1920 (and a facsimile reprint from Applewood Books is still available). Filled with instructions on how animated pictures were made as well as many shortcuts that could be used in creating animation, this book was discovered by Walt Disney while he was working at the Kansas City Film Ad Company. From the book, Walt learned the tricks of the trade from cycles to how to hold and repeat drawings. He used the book to instruct his first animation staff and continued to recommend it to aspiring animators during his early years in the business.

However, using this sole reference book for training was the exception. Most early animators were self taught and for the most part had aspired to careers in newspaper cartooning. Sometimes they were lucky to catch a few tips from some of the more gifted animators sitting at desks next to them like Ub Iwerks or Otto Messmer. These natural animators patiently helped new artists who often found themselves promoted overnight from cel washers to animators because of production needs.

There was no formal training at any of the studios because when an artist was hired he was already expected to know how to draw and to learn quickly on the job the requirements of animation because new product had to be produced weekly to be competitive.

Walt Meets Chouinard

One of the things that made Walt Disney a visionary in animation was his realization of the necessity of training in order to transform animation from a quickly fading novelty into a storytelling art form.

In an interview with Fletcher Markle on Sept. 25, 1963, for the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. show Telescope, Walt stated, The first thing I did when I got a little money to experiment, I put all my artists back in school. The art schools that existed then didnt quite have enough for what we needed so we set up our own art school. We were just going a little bit beyond what they were getting in the art school where they worked with the static figure.

Now we were dealing in motion, movement and flow of movement the flow of things, action, reaction and all of that. So we had to set up our own school and out of that school have come the artists that now make up my staff here and, more than that, the artists that make up all of the almost all of the cartoon outfits in Hollywood were directly or indirectly out of my school.

In 1931, barely four years after the birth of Mickey Mouse, Walt Disney made an arrangement with Mrs. Nelbert Chouinard to pay the necessary tuition to send his artists to the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles for night classes. Mrs. Chouinard, a Pratt Art School graduate, opened her own art school in 1921 and in less than a decade, it was listed among the top five art schools in the United States. It maintained that position for the rest of its nearly half century history.

Her faculty was composed of top working professional artists, and students were hand-selected and expected to work hard at the basics but encouraged to explore their own visions and interests. Walt was so committed to this training that he often drove the animators to school at night in his own car, returned to his studio to continue working and then drove back to pick them up after classes.

It was costly, but I had to have the men ready for things we would eventually do, Walt stated when asked why he was spending thousands of dollars during the Depression on this project, I hope to stir up in this group of men an enthusiasm and a knowledge of how to achieve results that will advance them rapidly.

Disney animator Art Babbit was also holding informal life drawing classes at his home during this time for fellow Disney animators and Walt quickly realized he needed to set up a Disney Art School on the Hyperion Studio lot itself to control the training and focus it more specifically on the needs of animation.

Don Grahams Innovative Training

Walt decided to hire Don Graham, an instructor at Chouinard and former engineering student from Stanford University, to supervise this new training in addition to his teaching responsibilities at Chouinard. Graham is remembered today as an inspirational instructor who was patient and articulate. Graham had an incredible knowledge of drawing and art history in addition to being an outstanding draftsman himself.

The very first class at the Hyperion Studio was on Nov. 15, 1932, with 25 artists in attendance. Older Disney animators smile when they recount that the attendance grew swiftly when it was discovered that Graham was demonstrating motion with the use of cute nude female models.

However, not all the animators eagerly embraced this formal training, especially since Graham had no background in animation. Many colorful cartoons started appearing around the studio bulletin boards including some featuring Disney characters with anatomically correct features to parody the classic life drawing training. Instinctive animators like Freddy Moore and Norm Ferguson felt there was little to be gained from this training. Moore told fellow animators: Graham can give you the rule. I would just say that it looks better.

Other Disney animators like the legendary Bill Tytla embraced the training and he told one training class, When I first came out here about two and a half years ago, they started having action analysis classes and I fell for them like a ton of bricks.

Graham had quickly adapted to the needs of the animators so instead of having a static model, he developed an action analysis approach where the model would do quick extreme movements like handstands and then disappear with the artists having to capture the motion they observed.

Originally the classes were held twice a week in the evenings with an emphasis on life drawing, composition, action analysis and quick sketch techniques. However, attendance grew so rapidly that Graham soon had to employ some assistants (including Gene Fleury and Phil Dike) when the program expanded to five nights a week. By mid-decade, the cost of this Disney Art School was conservatively estimated as costing Walt nearly $100,000 annually.

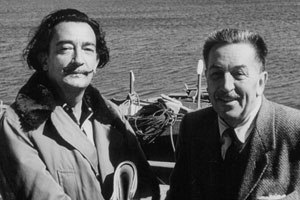

In addition, Walt brought prominent artists and intellectuals through the studio to lecture and consult. Some of these guest lecturers included Rico Lebrun, Jean Charlot, Thomas Hart Benton, Salvador Dali and Frank Lloyd Wright. Artists were immersed in every form of media from music to theater to dance to film and more.

Walts Memo

With Walts plans for the production of Snow White and the resulting increase in the number of new animators, Walt felt that the training needed to become even more rigorous so that aspiring animators brought to the studio for a tryout could be screened very quickly during the first few weeks to determine whether they should be hired as inbetweeners and apprentices.

In a lengthy memo dated Dec. 23, 1935, to Don Graham from Walt Disney, Walt outlined specifically the type of training that he felt was needed: Right after the holidays I want to get together with you and work out a very systematic training course for young animators, and also outline a plan of approach for our older animators. Some of our established animators at the present time are lacking in many things, and I think we should arrange a series of courses to enable these men to learn and acquire the things they lack.

Naturally the first most important thing for any animator to know is how to draw. Therefore it will be necessary that we have a good life drawing class. But you must remember Don, that while there are many men who make a good showing in the drawing class, and who, from your angle, seem good prospects these very men lack in some other phase of the business that which is very essential to their success as animators.

The talks given by Fergy, Fred Moore, Ham Luske and Fred Spencer, have been enthusiastically received by all those in attendance. Immediately following these talks, I have noticed a great change in animation. Some men have made close to 100% improvement in the handling and timing of their work. This strikes me as pointing a way toward the proper method of teaching in the future.

Graham took groups of artists to the zoo in Griffith Park to sketch animals. Artists spent half a day drawing in life drawing classes and half a day studying production methods. The night classes continued with an emphasis on animation, character drawing, layouts and backgrounds. Disney artists like Ken Anderson lectured on their specialty area and these lectures were dutifully recorded and mimeo-ed and distributed throughout the studio.

One Disney animator commented on the value of this training when he said, Before I started there I animated well and badly both. But I couldnt reproduce the former at will and I couldnt fix up the later. What the classes did for me was to give me consistency.

Certainly the superiority of the Disney animated product during the 1930s and 1940s can be credited to this training. No other animation studio invested the time and money for training. Many of the principles of animation from squash and stretch to secondary action to more came from these Disney training studies.

In the 1950s, when her school was in danger of closing, Mrs. Chouinard phoned her old friend and Walt Disney paid the mortgage and endowed the school with $10 million. Walt Disney was always committed to training for artists that would embrace exposure to everything from sports to ballet to film to music. It was his dream and vision to create such an specialized school for future artists, and that dream was realized in 1961 through the merger of the Chouinard Art Institute and the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music to create The California Institute of the Arts, commonly known as CalArts, with a campus now located in Valencia, California. It was the first degree-granting institution of higher learning in the United States created specifically for students of both the visual and the performing arts.

Of CalArts, Walt once said, Its the principal thing I hope to leave when I move on to greener pastures. If I can help provide a place to develop the talent of the future, I think I will have accomplished something.

Jim Korkis is an award-winning teacher, a professional actor and magician and a published author with several books and hundreds of magazine articles relating to animation, cartooning and film history to his credit. He is an internationally recognized Disney historian and has taught animation at the Disney Institute.